Pain of loss drives Derry family's nonprofit work

When the doctor asked if they would like to see their baby, Sean and Paige Green did not know what to expect.

Then they saw him, and “he was perfect,” said Sean Green, 36, of Derry.

“Fully formed,” recalled Paige Green, 37.

“Fingers, toes ... everything you would expect,” Sean said.

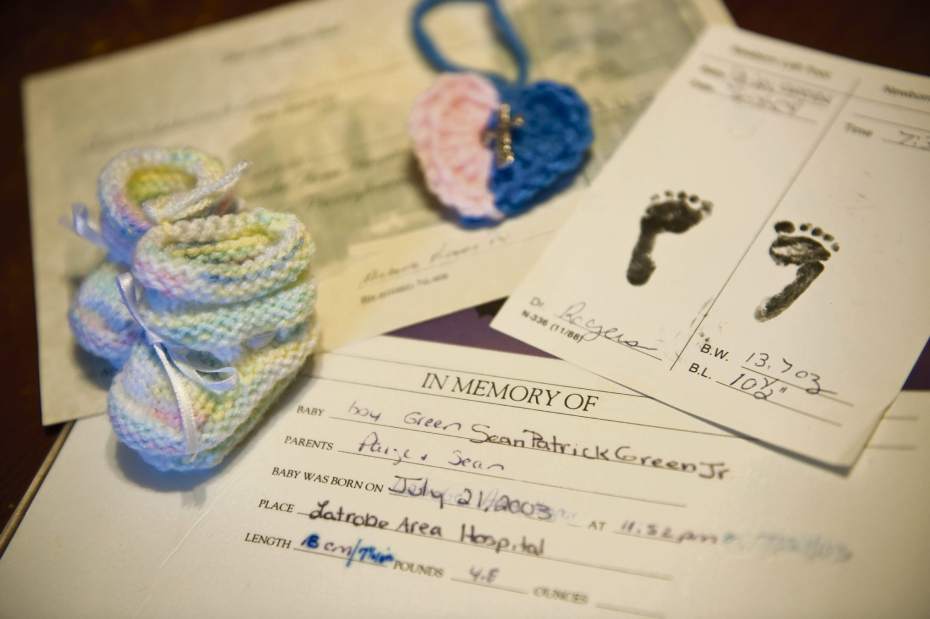

They named him Sean Jr. He was born July 21, 2003. He weighed 4.8 ounces and measured just over 7 inches.

They held him for two hours, then handed him over to the funeral home.

“Hardest thing I ever did was let him go,” Paige said. “I was numb. I thought: ‘What happened? What did I do?' ”

Nothing, doctors assured her. Sometimes it just happens.

So when Jessica began forming in her womb, Paige was scared but hopeful.

Through 20 weeks, everything was as it should be.

Then Paige began to bleed.

She went into premature labor. The details are hazy — Paige lost a lot of blood — but amid the chaos, she remembers a doctor sitting bedside and asking what she wished to do.

She told him that she wanted only for her baby not to suffer.

Jessica had a faint heartbeat when she was born on June 4, 2004. It did not last long.

She weighed 13.7 ounces and measured 10½ inches.

For the second time in less than a year, Sean and Paige Green held their silent baby.

“I sang her a lullaby,” Sean said. “When I finished, she fell asleep ... forever. It affects me to this day. But it's my memory. It's mine.”

Doctors suspected Paige had a T-shaped uterus, which increases the risk of miscarriages. But with a simple cerclage procedure to tighten her cervix, doctors told her, the next baby would live.

Several months later, Paige again discovered she was pregnant.

The first time she made this discovery — with Sean Jr. — she left the home pregnancy test on the sink and urged her husband to go to the bathroom. He went, and their home was a happy place that night.

This time, however, Paige felt terror.

“We'd lost two,” she said. “Even with a plan in place.”

At nine weeks, the baby was fine.

At 12 weeks, she went in for the cerclage.

But at 16 weeks, her water broke.

“I was numb,” Paige said, sitting on the couch of her dimly lit living room. “This was supposed to work.”

Issac was born Jan. 15, 2005. He weighed 3.6 ounces and measured 7 inches. He was so tiny that nurses struggled to get a footprint for the death certificate.

Again, Sean and Paige held him.

“All of my babies were perfect,” Paige said. “They were just born too soon.”

Paige was done.

This is too much, she told her husband. Never again.

Sean was a loving, supportive husband. And Paige knew he had suffered, too. But only she had carried the babies.

Three times.

A hospital counselor reached out, but Paige was not interested.

Unless you're a “loss mom,” she said, you can listen, but you cannot understand.

She sought solace online. She found chat groups and message boards for women like her. She read testimonies. She shared her own.

In time, she got involved with the Tears Foundation, which helps pay for the funerals of stillborns and babies who die in the first year. Paige is president of the Pennsylvania Chapter.

A fellow loss mom messaged her about Dr. Arthur Haney of Chicago, who specializes in reproductive and gynecological problems.

Paige was intrigued.

But she refused to hope.

So Sean did instead. He sent an email.

Dr. Haney replied at once. He called, and they spoke for 90 minutes. Paige listened.

On July 2, 2009, the Greens flew to Chicago for an operation called transabdominal cerclage. Haney would sew her cervix shut, permanently. The surgery would prevent Paige from giving birth naturally, but she could have a C-section. And her baby would never again emerge too soon.

A year later, Paige was pregnant.

Nine months after that, she gave birth.

This time, their baby cried.

“I heard this scream and I just started crying uncontrollably,” Sean recalled. “I thought, ‘I'm a dad. To a live child, I'm a dad.' ”

Kristopher Green was born Sept. 15, 2011. He weighed 7 pounds 11 ounces and measured 19 1⁄4 inches.

Sean held him first. The baby cried, but Sean did not care. He had a son, and he was alive.

An hour later, mom was wheeled back into the hospital room. She took her baby into her arms.

Again.

Finally.

“I had to give three babies to the funeral home, and I never heard any of them cry,” she said. “This time, my baby cried. I finally got to be a mom.”

On Kristopher's first birthday, Paige bought balloons. She wrote messages on them to the first three. Then they released them to the heavens. They observe the same private ceremony every year.

Kristopher will be 5 soon. He plays in the yard, near a garden dedicated to his brothers and sister, where three ceramic toddlers lower their heads against the base of a dogwood tree, hiding their eyes in the crooks of their arms as if perpetually suspended in a carefree game of hide-and-seek.

His parents don't often share their losses with strangers. With Kristopher they make a point of it. In the beginning, his siblings were abstract people he'd never met.

Recently, however, he learned their names.

He repeats them often, to anyone who will listen, sometimes to himself: Sean Jr., Jessica and Issac.

Kristopher is in preschool, where classmates and school officials see him as an only child.

But on a recent school visit, his teacher approached Paige with concern.

“Kristopher says he has brothers and a sister,” the teacher said.

Paige smiled.

“He does.”