Author details Jimmy Stewart's military service in new book

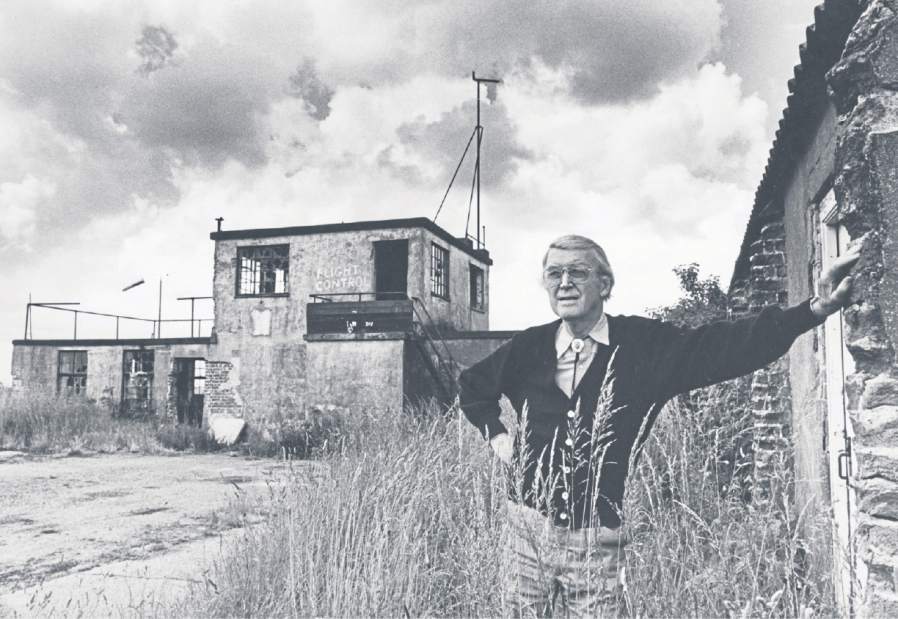

On Aug. 31, 1945, Jimmy Stewart arrived back in the United States from England, where he had served in the Army Air Corps. He'd joined as a 34-year-old private but was discharged as a colonel who led 26 air combat missions in Europe, most of them successful. Stewart was awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross and other honors.

His return to the States, however, left him unsettled. Stewart lingered near the British liner the Queen Elizabeth that day, waiting for his “boys” to disembark, avoiding the press. He would later say, “I didn't want the moment to end.”

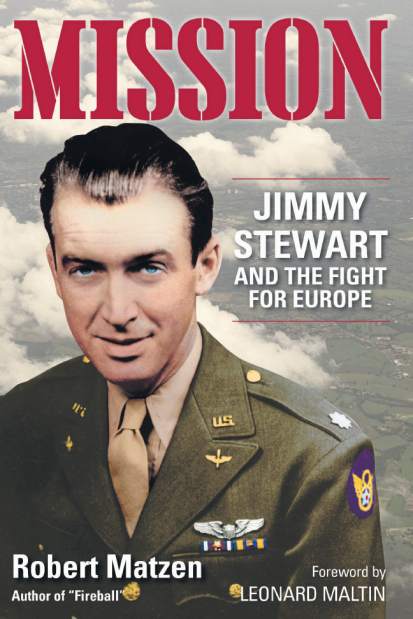

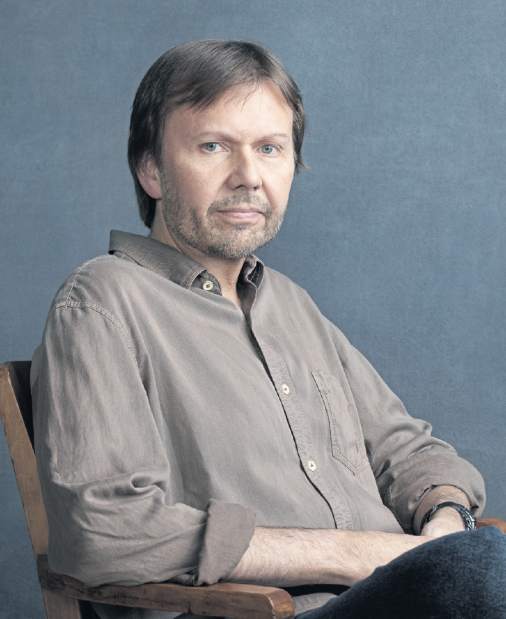

“He felt like he was part of something very important,” says Robert Matzen of Bethel Park, author of “Mission: Jimmy Stewart and the Fight for Europe” (GoodKnight Books, $28.95). “It was part that, part what they did, who they fought and how important that was. It was part the camaraderie of being with those guys and pulling off what they did, doing it together.”

Matzen will appear Nov. 19 at the Jimmy Stewart Museum in Indiana, Indiana County.

“Mission” provides an in-depth look at Stewart's military service and how it became (until he married Gloria Hatrick McClean and had children) the most important event in his life. Before World War II, the Indiana native had achieved fame and acclaim for his acting, winning an Academy Award in 1941 playing a newspaper reporter in “The Philadelphia Story.” He was a ladies' man who had dalliances with Norma Shearer, Ginger Rogers, Marlene Dietrich, Dinah Shore, Margaret Sullavan and Olivia de Havilland.

But the small-town boy who had been a film projectionist at the Ritz Theater in his hometown and who reveled in the appearance of a barnstorming pilot in Indiana when he a child — early indications of his love of film and flying — was subject to fits of boredom. When World War II broke out, Stewart was eager to enlist and leave behind the growing disenchantment he felt in Hollywood.

Stewart, however, was classified as 1-B and given a deferment because he was 6 feet, 4 inches tall and weighed 139 pounds. Louis B. Mayer, the co-founder and head of MGM Studios, was especially keen on Stewart keeping his deferment and fulfilling his military obligation at the Army Air Corps Motion Picture Unit at Wright Airfield in Dayton, Ohio.

Stewart persisted and was reclassified 1-A. When he got his first combat assignment, it was “a key moment in his life,” Matzen writes.

“He finally was able to influence the right guys,” Matzen says, “the right leaders who were willing to take a chance and get him that assignment. Why they were willing to stick their necks out for him, that's tough. But they did.”

The leaders who had faith in an older pilot — most of Stewart's fellow pilots were at least 10 years younger than he was — were rewarded.

“The breadth of his experience, the fact that he had a close association with someone like Louis B. Mayer, that he had dealt with Hollywood's top brass, meant that he could deal with military brass,” Matzen says. “He could make more mature decisions than these young guys. He had a good head on his shoulders and was very smart. And he was a clear communicator. I heard from more than one person the fact that you heard his voice on the interphone (in aircraft) was very important because you understood every single word he said. When you were at 20,000 feet in battle conditions, that's very important.”

When Stewart returned home, he initially had trouble restarting his acting career. Hollywood had changed and younger leading men were in favor. When director Frank Capra offered him the role of George Bailey in “It's a Wonderful Life,” Stewart initially resisted the role. Fortune smiled on Stewart, but not right away: The movie that would eventually define his career, and even his life, was not a hit.

“It's a Wonderful Life” has passed the test of time and become one of the rare films of the era that holds up today. But affection for the movie should transcend nostalgia. Matzen couches it this way: One year prior to Stewart filming a Christmas scene in a desert, he was commanding a squadron in life-threatening situations.

“When you look at ‘It's a Wonderful Life' from now on, you should have a greater appreciation for him because of what you now know that went on in his life,” Matzen says. “What went on behind his eyes when he played George Bailey is incredible.”

Rege Behe is a Tribune-Review contributing writer.