Carnegie Museum of Natural History unveils new dino discovery

There are many subtle gradations of excitement out there, from pennant-race baseball thrills to kid-on-Christmas-morning exhilaration.

Then there's the excitement of paleontologists who discovered a complete titanosaur skull — and a new species of dinosaur.

Giddy doesn't begin to describe it.

The scientists shared the experience at Carnegie Museum of Natural History on April 26 when the discovery of the new dinosaur was announced.

Museum paleontologist Matt Lamanna described a video he saw of the actual discovery in a remote part of Argentina, done by his longtime colleague and collaborator Ruben Martinez, of Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia San Juan Bosco, Argentina.

Lamanna said he watched as bits of rock were chipped away. As the scientists began to realize the vertebrae they had unearthed were connected to more, and the trail kept going up the neck ... Could it really be a head?

“The moment of truth was when (Martinez) flicked off a piece of rock, and there was enamel from the teeth glinting in the sunlight,” Lamanna said.

Intact skulls are supremely rare. This one is likely the best-preserved skull in existence for a titanosaur. A bright-white replica of the skull sat before the scientists. The original remains in Argentina.

Martinez named the dinosaur Sarmientosaurus musacchioi, after the small town close to the discovery site, and the late Eduardo Musacchio, a paleontologist and friend of Martinez and Lamanna who died in a plane crash in 2011.

The discovery was reported in the PLOS One (Public Library of Science) journal on Tuesday.

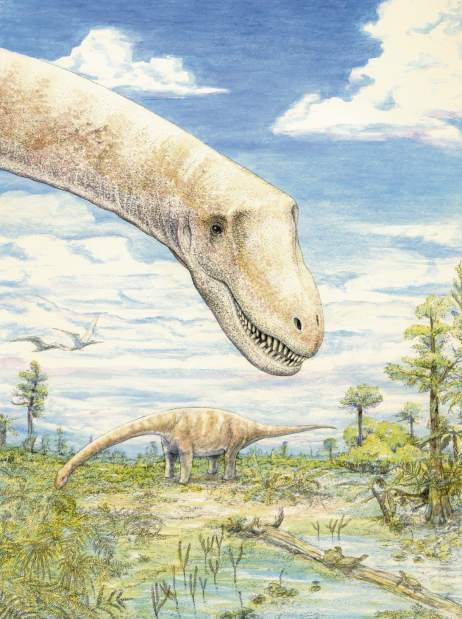

The Sarmientosaurus is part of the grouping known as titanosaurs, which are the largest animals to have ever walked the Earth. They are plant-eating, tiny-brained sauropods like the better-known Diplodocus, from which the “Dippy” statue outside the Carnegie Museum is modeled.

The Sarmientosaurus weighed 8 to 12 tons, and was 40 to 55 feet long. For comparison, a large elephant is about 5 tons.

“Discoveries like Sarmientosaurus happen once in a lifetime,” said study leader Martínez. “That's why we studied the fossils so thoroughly, to learn as much about this amazing animal as we could.”

Martinez had the idea to do a CAT scan of the delicate skull and send the information to paleobiologist Lawrence Witmer of the Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine in Athens, Ohio, one of the world's experts in the skull anatomy of vertebrate animals. Witmer made a 3-D-printed replica of the skull, and another of its brain, created by measuring the skull cavity where the brain would have once been.

“Years ago, to study the brain, you'd have to saw the skull in half,” Lamanna said. “The brain is about the size of a lime. Sarmientosaurus wasn't doing advanced calculus, or anything like that. But even though they didn't have a lot of brain power, they were able to last millions of years, while their brains stayed more or less the same.”

An intact skull can tell researchers so much, from what the creature ate, to information about its large eyeballs and an inner ear tuned to hear low-frequency airborne sounds. This could indicate that it may have communicated with other titanosaurs, or was able to find the rest of the pack by their footfalls.

Scientific discoveries seem to move as slowly as lumbering dinosaurs. The skull was actually found it in 1997.

“It had never been given an official name and studied until now,” Lamanna said. “Sometimes it takes awhile to squeeze all of the information out of a dinosaur.”

Replicas of the skull and brain will be on display at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in a few days, with some interactive displays designed by Witmer and his team.

Details: www.plos.org or www.carnegiemnh.org

Michael Machosky is a Tribune-Review staff writer. Reach him at mmachosky@tribweb.com or 412-320-7901.