Former giant U.S. Steel reorients goal to get profit

At the height of its production in the 1940s, U.S. Steel employed 15,000 workers at its sprawling Homestead Works along the banks of the Monongahela River.

If the company follows through on layoff warnings issued this year, U.S. Steel would have fewer employees than that at all of its American facilities combined.

The birth of U.S. Steel in Pittsburgh in 1901 through the purchase of Andrew Carnegie's empire by J.P. Morgan and Elbert Gary amounted to the largest business enterprise started at that time. It made two-thirds of steel produced in the United States.

As it prepares to move from Pittsburgh's tallest skyscraper to a five-story office building Uptown, the former giant does not rank among the top 10 steel producers in the world. A push to streamline operations, cut costs and invest in technology — dubbed the Carnegie Way initiative for its famous forefather — likely will change its once-imposing figure more.

“It's a symbolic transformation, that move,” said James Craft, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh's Katz Graduate School of Business. “U.S. Steel and Pittsburgh have both made transformations in who they are. They reflect each other.

“The name is the same, but the look is different.”

U.S. Steel officials declined requests for interviews on how the steel producer became such a dominant force and what has happened since to the corporation and the industry at large.

“We've taken aggressive and decisive actions to address the extremely challenging conditions we are currently facing in North America,” CEO Mario Longhi, who has led U.S. Steel for two years, told analysts in April, citing competition from cheap imports and a collapse in energy industry activity.

Western Pennsylvania workers, union officials, community leaders, analysts and preservationists have held front-row seats to the transformation during the past half-century. The Tribune-Review spoke with several about the company's transformation.

Ron Baraff

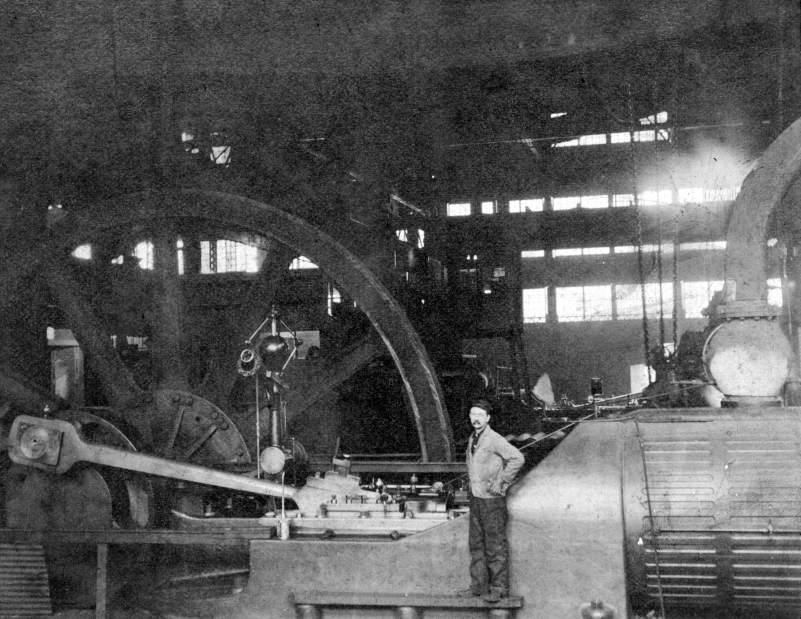

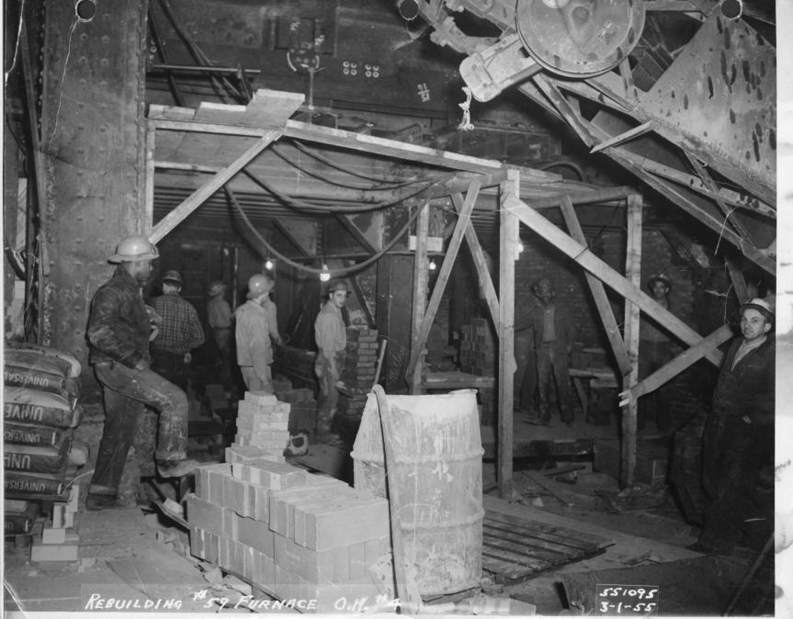

When Carrie Furnaces 6 and 7 came online in Rankin in 1907, the man-made volcanoes were “technological marvels,” said Ron Baraff, director of museum collections and archives at the Rivers of Steel National Heritage Area.

“This is where U.S. Steel helped create America's 20th century,” Baraff said, standing in the shadows of the 92-foot-tall blast furnaces that once churned out more than 1,000 tons of molten iron a day. He oversees tours of the furnaces and surrounding buildings.

The hulking furnaces — the only examples from that era standing — symbolize what made the company so strong for the first half of their life and their eventual decline.

They consumed four tons of ore, coke and limestone for every ton of iron they produced for use downriver at what was U.S. Steel's largest mill at Homestead Works. They consumed copious amounts of labor to keep them working.

“You'd work six days a week, 12 hours a day, and every other Sunday,” Baraff said, noting a lack of union strength until after World War II. “... You were just another raw material.”

U.S. Steel relied on the size of its workforce and equipment to a fault, Baraff said, failing to reinvest in the furnaces before it was too late. When the last furnace went cold in 1978, they were long obsolete.

The company abandoned the site, letting it fall into ruin before Congress established the heritage area in 1996. Despite what some visitors believe, U.S. Steel does not financially support the site, Baraff said.

“I think (U.S. Steel) sees this site as a failure and not a success,” he said. “I see a heroic story here.”

Raymond Bodnar

Raymond Bodnar remembers all the people streaming into his hometown of Munhall, buses full of workers at the mills collectively known as Homestead Works.

“They were coming from Uniontown and Westmoreland and all over southwestern Pennsylvania,” said Bodnar, 81, the borough's mayor. “They were just hiring constantly.”

He recalls going to the hiring office at 9 o'clock one morning in 1951; he went to work on the 3 p.m. shift that day and spent the next 41 years employed by U.S. Steel.

“I couldn't believe the amount of steel coming out of there,” said Bodnar, who worked on the 45-inch rolling mill and a 160-inch treating line before moving to the corporate office, then at 525 William Penn Place, Downtown.

“I would have bet you my life that never would have closed.”

Some of his neighbors recall a company that laid off workers just shy of eligibility for benefits.

Bodnar remembers libraries, swimming pools and air conditioning U.S. Steel provided for communities in the valley, and the items the company donated to towns to maintain roads and bridges.

The cost of maintaining the mills with increasingly burdensome union contracts became too much, though.

“The competition got too heavy, not just from other companies but from their own plants,” he said.

When the last mill closed on the site in 1986, U.S. Steel walked away, leaving the communities it once supported alone to deal with redevelopment.

“I knew eventually something would be built, but I thought we would have been dead and gone by then,” Bodnar said of The Waterfront retail and entertainment complex that eventually took its place. “But now we have people coming in from out of town again — from Swissvale and Braddock and Monroeville.”

Tom Conway

Tom Conway says he has watched a “long historic slide” for the steel industry since he started as a millwright in the 1970s.

As slow as companies such as U.S. Steel were to embrace technology and deal with competition, elected leaders failed to protect the industry from cheap imports, he said.

“It really is about allowing your market to sort of be overtaken by people who are positioned to be able to undercut you,” said Conway, who as international vice president for Pittsburgh-based United Steelworkers of America has been involved in union contract negotiations for decades.

“Look at the current climate: It's frustrating and flabbergasting in this gas market, in the Marcellus shale, you can't get your steel to market because Korea can do it cheaper.”

He acknowledges that onerous labor contracts weighed the company down in the 1980s when U.S. Steel could have made the moves toward efficiency that it's making today. The company did not help itself, Conway said.

“There was an arrogance to them,” he said.

As the union prepares for a round of contract talks, the company has agreed to reduce its use of outside contractors and its overhead.

“I see this most recent iteration of management; they're making decisions that are smart,” Conway said. “We spent decades in a daily knife fight with U.S. Steel over, ‘You have a contractor doing what employees should do.' We have begun to turn that corner.”

James Craft

Longhi's influence on turning U.S. Steel into a more efficient and focused company is showing, said the University of Pittsburgh's Craft.

Before the most recent round of layoffs, U.S. Steel in 2014 posted its first profit in years. It's building next-generation electric arc furnaces in Alabama that would allow it to use scrap steel, be more competitive and lower costs. It recently recalled nearly 150 laid-off workers there.

“The changes suggest U.S. Steel is reorienting itself to be more competitive. But just think if they had done this in the '70s and '80s,” Craft said.

Changes were aimed at diversification or expansion, he said, noting the company's purchase in 1982 of Marathon Oil.

He expects U.S. Steel to emerge from this cycle as a different company.

“Its goal isn't to be the biggest anymore; it's to be profitable,” Craft said.

David Conti is a Trib Total Media staff writer. Reach him at 412-388-5802 or dconti@tribweb.com.