Grieving Hempfield parents speak on son's death, organ donation

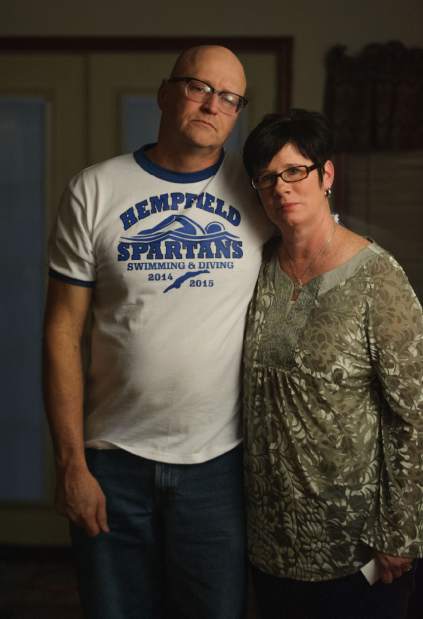

Meg and Bill Shiffler faced a sudden, wrenching goodbye.

As their teenage son fought for his life at UPMC Presbyterian, doctors told them swelling had severely damaged his brain.

It was time for the unthinkable — talking about Judson “Jud” McQuaid Shiffler's decision to be an organ donor.

“It's a blur,” says Bill Shiffler, 54, of the agonizing time in the hospital surrounded by family and friends. “It's a nightmare. You become numb. It's like a bad movie. And you can't fathom what you are hearing and what the doctor is telling you.”

The Shifflers spoke about their son's Dec. 30 death for the first time to create awareness about organ donation, a choice they supported. Five people received Judson's organs — his heart, kidneys, liver and pancreas. His lungs and eyes were donated to research.

Bill Shiffler, an Irwin native, and his wife Meg, a Greenfield native, sat in the living room of their Hempfield home remembering the boy with the quirky sense of humor who started swimming as a fifth-grader at the Greensburg YMCA.

The Hempfield High School team captain signed up to be an organ donor the day he got his driver's license.

“Dad, this is what I need to do,” he told his father. “If something happens, I am not going to need my organs in heaven, so if someone could use them, I would want that.”

Two years later, as he drove home from swim practice — one he didn't have to attend because of his good grades — he crashed his tan Chevy Cavalier into a hillside. His death devastated his parents, sister Natalie, relatives, members of his swim team and others in their community.

“I am so proud of him being an organ donor, but I just miss him so much, you know?” Bill Shiffler says.

Tears to fill a pool

Judson Shiffler was a WPIAL Class AAA champion in the 50-yard freestyle. He was the first individual gold-medal winner in boys swimming at Hempfield, where he held three school records.

He liked to swim in the fourth lane of a pool because he considered it the fastest. On the day after the accident, his teammates gathered in lane 4.

They talked, laughed, cried, and shared stories about their leader, the one who showed them more than the perfect stroke in the water.

“Jud helped save five lives that day — five people who no longer have to wait and who can see the sunrise,” says coach Kevin Clougherty. “I had Jud in class, and we were discussing the role of the individual in society. He said, ‘It's easy to say if you want to make the world a better place. The challenge is doing it, making the change.' ”

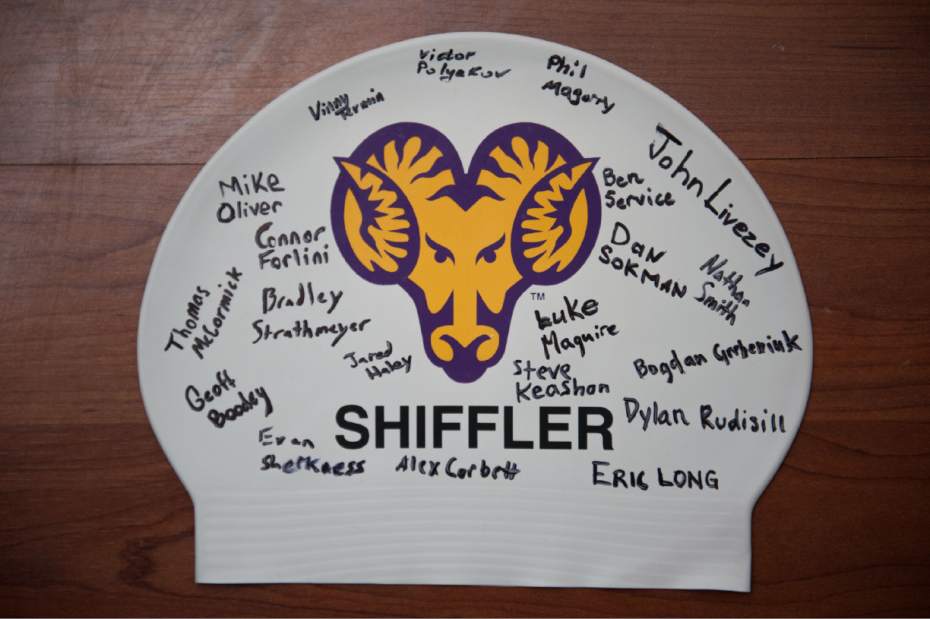

The star swimmer had shown his teammates his organ-donor designation on his driver's license. At the time, his teammates didn't give organ donation much thought, says junior Justin Katchur. Now, they all want to be organ donors.

“We all looked up to Judson. He worked harder than anyone else. He put in the effort every day,” he says.

Teammates described their captain as someone who would give up a spot in the lineup so other swimmers could compete.

“He was inspiring,” says sophomore Zach Rulli, who moved into Judson's spot in the freestyle leg of the medley relay. “I can never replace him. No one can.”

Although Judson Shiffler didn't like to be in the limelight, friends and family have made sure he's not forgotten. On the team's first meet following his death, his lane remained empty during the 200 medley relay. Three of his teammates swam. Opponent Greensburg Salem did not swim in that event as a tribute to Judson.

Then there was a banner presented to the family by members of the Franklin Regional High School. “Heaven just got a little faster,” it read. The phrase spread on Facebook during the days after Judson Shiffler's death and appeared on T-shirts the swimmers wore.

“We have our good days and our bad days,” says Meg Shiffler, 53. “We have cried a lot — probably enough to fill a swimming pool.”

Her son had qualified for every event at this year's WPIAL swimming championships. She and her husband attended the championship's opening day in February at the University of Pittsburgh.

On what would have been their son's event, his teammates huddled at the edge of the pool and waved to the couple. And on senior night at the high school, several of the swimmers escorted the grieving parents.

“We cried,” Meg Shiffler says. “We love the Hempfield swim team and all swimmers. We are all family, and Bill and I will continue to support them and encourage them to carry on what Jud started.”

Urge to swim?

Meg Shiffler says she would like to meet the people who received her son's organs someday. She and her husband aren't quite ready.

“I do wonder if they all have the urge to jump in a swimming pool since they have Jud's organs,” Meg Shiffler says. “I bet they do. And they probably want to jump into lane 4. We will have to wait to find out.”

Most people wait about a year or longer to meet organ recipients because the time allows the donor's family to heal emotionally and recipients to get physically stronger, says Misty Enos, director of professional services and community outreach for the Center for Organ Recovery and Education in O'Hara.

“The recipients may have survivor's guilt,” Enos says. “They know someone had to die for them to live. They are appreciative but might not have the words to express thank you for the life they have been given.”

Meg Shiffler says she often wears her son's athletic socks to keep her feet warm on cold nights and her heart feeling his presence. She saved the last two text messages he sent — one is a picture of a pizza he was sharing with his girlfriend, Molly Sternick, a junior swimmer for Hempfield.

Bill Shiffler bears a mark on his finger from a thorn that got stuck when he was climbing the hill at the site of Judson's accident. He had to see where it happened.

As they continue to heal, the Shifflers say they take solace in knowing their son lives on through others.

“The people he has touched through this — young kids wearing the bracelets and people wanting to be organ donors,” Bill Shiffler says. “We are so proud.”

JoAnne Harrop is a staff writer for Trib Total Media. She can be reached at 412-320-7889 or jharrop@tribweb.com.