Kids learn to bust a move at chess club in Hazelwood

Patrice Church studies a chess board and contemplates her strategy for capturing the king.

It's a Tuesday night at the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh in Hazelwood, and Church and her daughters, Isabella and Chloe Bolden, ages 9 and 8, respectively, are here to learn an ancient game often touted as a metaphor for skillfully navigating life's challenges.

“It said on the flyer, ‘Kids who play chess learn to think before they move.' I liked that,” says Church, who decided to sign up along with her kids.

“It's a little difficult trying to remember all of the ways the pieces can be moved, but I'm getting it,” she says. “My biggest challenge is not getting beat by a 12-year-old.”

Although parents are welcome, the club is designed for ages 10 to 16, and it has quickly taken off. Launched in November by the city of Pittsburgh Bureau of Police, the club has morphed from an initial gathering of four kids to more than two dozen, each looking to learn chess or to hone their existing skills.

“It challenges me to think,” says Kadence Boykin, 11, of Hazelwood, who was facing off against Flynn Godfrey, 11, of Greenfield. Godfrey has been coming every week with her sister, Zedueh, 9.

“They enjoy it,” says their mother, Gina Godfrey, who watches them play. “You hear a lot about how chess helps you develop cognitive skills, but that's icing on the cake. They're making new friends in a familiar environment, and it's held every week, so it's an activity they can count on. It's fun for them.”

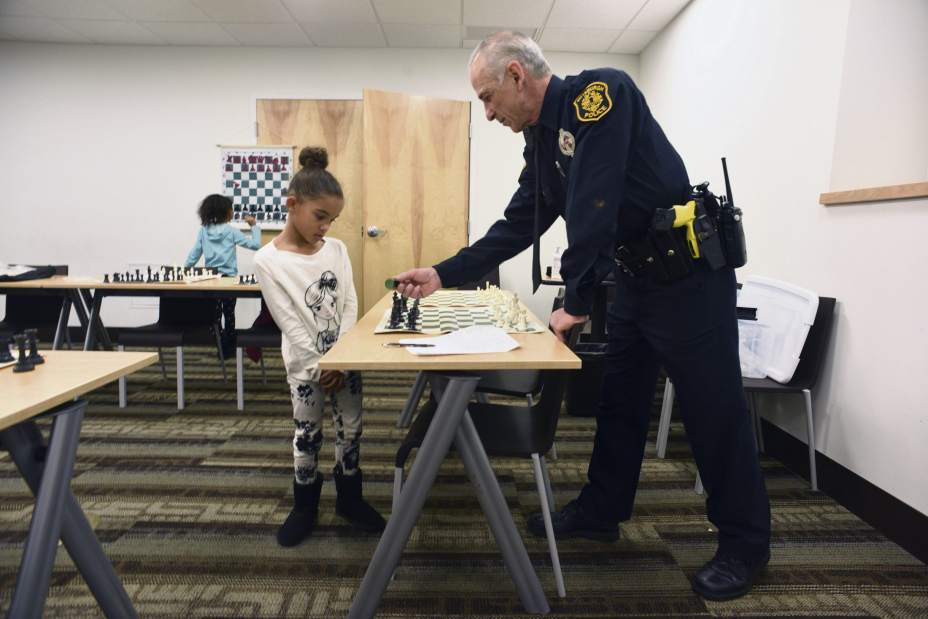

For the bureau of police, the chess club is about bringing a constructive activity to a higher-crime neighborhood and building greater trust in law-enforcement personnel, says Officer David Shifren, who started the club and hopes to see it taken citywide.

His inspiration, in part, was the Chess-in-the-Schools program in his native New York City. Since 1985, the after-school program has helped students in low-income areas develop critical-thinking and problem-solving skills. Educators say participants' test scores have improved, along with their ability to handle real-life situations. The program at Intermediate School 318 in Brooklyn has been called the best middle-school program in America and became the subject of the award-winning 2012 documentary film, “Brooklyn Castle.”

According to Afterschool Alliance, 80 percent of Americans want children to have safe after-school options.

“In a challenged neighborhood, kids don't always have positive activities to go to,” says Shifren, who patrols Hazelwood. “If this can save even one kid or a few kids from going off with the wrong crowd and getting into trouble with police, it's worth it.”

Chess teaches children the importance of abiding by rules, learning from mistakes, sacrificing small losses for bigger gains, winning with modesty and losing with grace, he says.

Although the bureau performs community outreach through organized sports, such as kickball, and the arts, it seized on chess as a way to encompass even more children.

“Dave (Shifren) really gets it,” says John Tokarski of the department of public safety, which provided the chess sets. “This introduces kids to public-safety personnel in a friendly way, as people who want to teach them.”

Church, a longtime Hazelwood resident, thinks the program was a smart move. “The culture here can be that the police are enemies, but that's not the case,” she says. “It's important to support the police and foster better relationships.”

“I enjoy the fact that police are doing this,” says James West, 17, of Hazelwood. “It gives them more of a presence among young kids, who can see, ‘Oh, the guy teaching me chess is an officer. He's a good guy.' ”

Hazelwood is a community in transition but still struggling to rebound from the closing of steel mills decades ago. According to neighborhoodscout.com, the average income in Hazelwood is lower than in 96.1 percent of U.S. neighborhoods, and it has a higher rate of childhood poverty than 73.8 percent. The number of reported crimes in Hazelwood is annually higher than the city, state and national averages.

In the face of such challenges, community activists have stepped up to help families improve their lives through organizations such as POORLAW (People of Origin Rightfully Loved and Wanted) and Center of Life. Neighborhood leaders have embraced the chess club as another grassroots effort.

“Kids need structure, and this gives them that, and they're learning at the same time,” says Saundra Cole McKamey, executive director of POORLAW, who praised Shifren in particular. “Children shy away from police because there's not enough positive outreach. David has no hidden agenda. He's doing this from his heart.”

The Hazelwood library is a hub of activity, especially during the week, when it becomes packed with children seeking somewhere to go after school, according to library manager Mary Ann McHarg.

“They'll come here when the bus lets them off around 3:30, and they'll stay for hours, and then they'll walk home,” she says. “The chess club has been fantastic in that the kids have responded. The number (of participants) has grown every week. What more could you ask for?”

As word of the club has spread, so, too, has support. Allegro Bakery in Squirrel Hill donated cookies one week, and Kim Allen, owner of Fat Rai's across the street from the Hazelwood library, has furnished pizza and posted flyers.

“I support it to the utmost,” says Allen, who fed the homeless on Thanksgiving Day and is sponsoring a purse drive for homeless women. “Kids need something like the chess club to feel this is their community and a community that's safe.”

Deborah Weisberg is a contributing writer for Trib Total Media.