https://archive.triblive.com/lifestyles/theater-arts/gentlemans-guide-to-love-murder-gets-the-look-by-breaking-rules/

'Gentleman's Guide to Love & Murder' gets the look by breaking rules

Joan Marcus

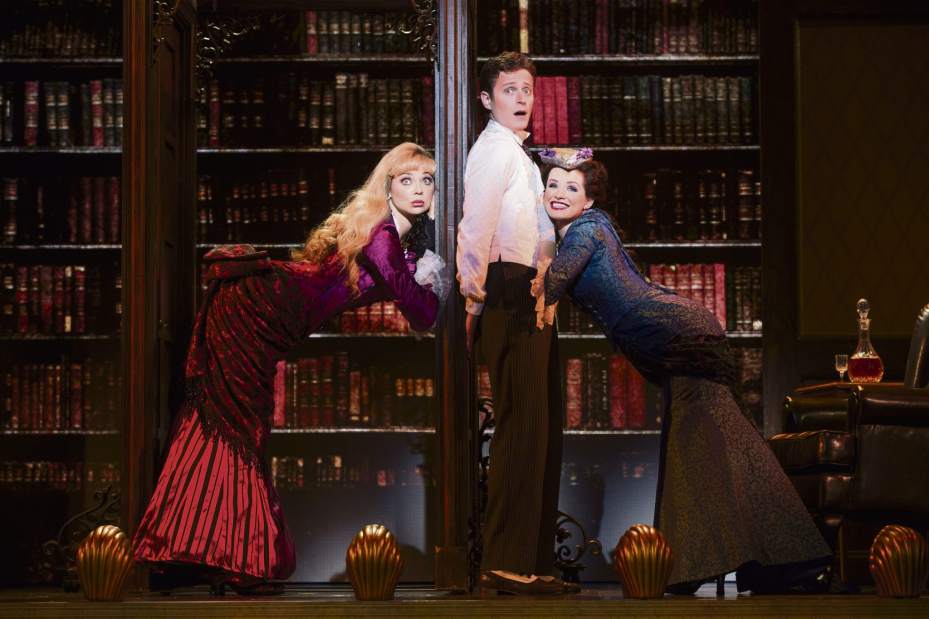

Kristen Beth Williams as Sibella Hallward, Kevin Massey as Monty Navarro and Adrienne Eller as Phoebe D'Ysquith in a scene from 'A Gentleman's Guide to Love & Murder.'

For costume designer Linda Cho, the best part of her job occurs long before she takes scissors to fabric or sees her costumes on stage.

Like many who create costumes or scenery for stage or screen, Cho enjoys researching the world in which the characters operate.

“It's an excuse to go to museums, watch movies and gather all the information,” Cho says. “It's like being a student again, but without the exams.”

Her work on the 2013 Broadway musical “A Gentleman's Guide to Love & Murder” — for which she received the Tony award for best costume design — was no exception.

In creating the costumes for the Broadway original, she drew on a variety of styles from Victorian-era clothing for older male characters to contemporary garments by Jean Paul Gaultier.

As the musical is still running on Broadway, she created a second set of costumes for the musical's national touring production, which begins performances Nov. 17 at the Benedum Center, Downtown.

“A Gentleman's Guide to Love & Murder” is set in Britain during the Edwardian period that spanned King Edward VII's rule from 1901-10.

The spoofy, farcical musical comedy is based on the 1907 novel “Israel Rand: The Autobiography of a Criminal,” which was the source of the 1949 film “Kind Hearts and Coronets.”

Writer and lyricist Robert L. Freedman and composer and lyricist Steven Lutvak pay homage to Gilbert & Sullivan operettas and music hall routines in their giddy romp about Monty Navarro, an impoverished gentleman who learns he is just a few murders shy of becoming the ninth Earl of Highhurst.

Eight members of the D'Ysquith (pronounced DIE-squith) family stand between him and the title. If he can eliminate them, he may be able to inherit the family fortune and regain the affection of the upwardly aspirational Sibella Hallward.

At the same time, he's got to juggle his mistress; his fiancée, who is also his cousin, and the constant threat of landing behind bars.

Creating period costumes for contemporary audiences comes with some special demands. To be successful, the clothing must invite the actors and audience into a long-gone world that had a very different look and outlook. At the same time, those hats, jackets, gowns and neckwear — and the characters who wear them — must appeal to those in the audience.

Completely authentic costumes would have dictated specific colors, lines and fabrics for specific activities or times of day — both for women and men.

Cho's designs create a bridge between period styles and present tastes “by making up my own rules,” she says. The customs of the period “would have been very prescribed. Women often changed four times a day.”

To illustrate, she describes a dressing gown Sibella wears in her first scene: “Some of the lines are Edwardian ... but obviously the bright pink would not be a color of the time,” she says. “Also there is a lot of skin and shoulders that would not be revealed.”

Cho had to design for demands of the production, such as multiple quick changes for ensemble members who may play as many as 12 to 16 roles during a performance. Actor John Rapson, for example, plays all the potential murder victims — from a do-good dowager to a Boer War vet.

“This show is all about quick changes,” she says.

She enjoyed creating a new set of costumes for the national tour, she says.

“It has been fun to do this all over again.”

Alice T. Carter is a contributing writer for Trib Total Media.

Edwardian flashback

“A Gentleman's Guide to Love & Murder” takes place during the Edwardian period roughly 1901-1910 — when Queen Victoria's son Edward VII ruled over Great Britain and its empire. It was an era of rapidly changing technology and social behavior, as well as a formal, elegant time with rules on the proper way to dress, eat, work and spend your leisure time.

Here are a few examples:

• An upper class woman was expected to change her outfit five or six times a day. She would wear a different outfit and hairstyle for each meal, when she received visitors, when she called on others, went to the theater or engaged in sports.

• Edwardian corsets were not as tight and restrictive as those of the Victorian period. Dresses, gowns and even blouses closed in the back. Ladies and even some female servants had to depend on someone to help them whenever they dressed or undressed.

• The house party was a popular way for wealthy people to spend their abundant leisure time. Generally running from Saturday to Monday, at a large country house, guests, particularly male guests, would engage in fox hunts, fish and shoot game birds. Evenings were filled with elaborate banquets, musical entertainments, card parties and games.

• Housemaids were expected to do their work without being seen or heard. If a member of the family they worked for or a guest did happen to encounter them, they were expected to stand, avert their eyes and not speak.

• At the end of an elaborate banquet or dinner party, the ladies would rise and leave the room together. They would reassemble for coffee in the drawing room while the men remained at the table for port, brandy and cigars before they rejoined the ladies.

Source: www.pbs.org/manorhouse/edwardianlife

Copyright ©2025— Trib Total Media, LLC (TribLIVE.com)