Baseball great 'Terrible Ted' Page to get overdue respect

Nearly three decades of quiet obscurity will end soon for a former outfielder on arguably some of the greatest baseball teams ever to kick up dust on a diamond, though their skin color prevented them from proving it in the World Series.

A ceremony on Saturday at Allegheny Cemetery is planned to place a marker on the fresh grave of Theodore Roosevelt “Ted” Page, a member of the storied Pittsburgh Crawfords and Homestead Grays who was bludgeoned to death in 1984 in his Hill District home.

Until recently, his cremated remains waited unclaimed in a community vault at the Lawrenceville cemetery where he once raised money to mark the grave of former teammate and baseball legend Josh Gibson.

“I'm glad to know his ashes were found,” Leslie Davis, 53, of the Hill District said of the great uncle who treated her late father like a son. “I was ashamed of that. Now this mystery is solved.”

Page becomes the latest recipient of generosity from the Negro Leagues Baseball Grave Marker Project, an initiative started in 2004 by Dr. Jeremy Krock of Peoria, Ill., with help from the Society for American Baseball Research. The project has provided granite markers for 27 players, most of them installed without ceremony.

Krock, who will attend with his family, hopes to have a minister give a eulogy, read Page's biography, allow family members and the public to speak, and perhaps finish with a rendition of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame.”

“I'm proud we can honor these players in this small way,” said Krock, who is white. “We hope to keep the memory of the player alive and to keep the memory of Negro League baseball alive.”

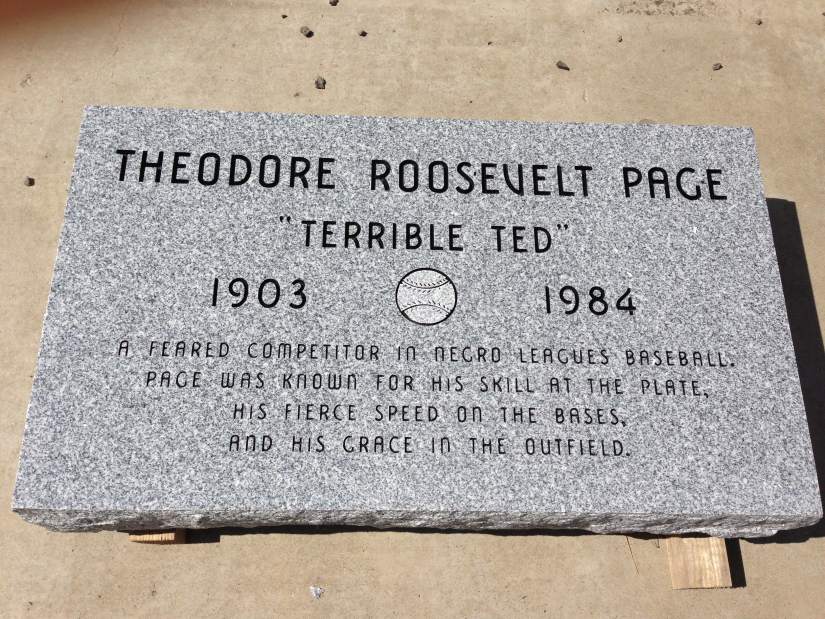

Krock and others worked for two years to raise money for Page's marker, which refers to his nickname “Terrible Ted” and states: “A feared competitor in Negro Leagues baseball. Page was known for his skill at the plate, his fierce speed on the bases and his grace in the outfield.”

Davis will be out of town for the ceremony but hopes other family members and people who remember Page will attend.

“I'm truly humbled and appreciative that these relative strangers appreciate what these old black men did almost 100 years ago,” she said. “It's a big vote of confidence and a sign of respect. I'm proud to have been related to this man.”

Born in Kentucky in 1903, Page grew up in Youngstown, Ohio.

He started in semipro, sandlot baseball in 1923, making $10 a game. He soon graduated to “big-time black baseball” on teams such as the Brooklyn Royal Giants, New York Black Yankees, the Grays and the Crawfords, where owner Gus Greenlee paid him $200 a month to play for his Hill District team. A knee injury robbed Page of his speed, and he finished his career in 1937 with the Philadelphia Stars.

After baseball, Page ran bowling alleys, including Meadow Lanes in Homewood. He wrote a sports column for the Pittsburgh Courier and became a public relations consultant for Gulf Oil Co.

A paperboy found Page, bleeding, on the floor of his Bryn Mawr Road home on Dec. 1, 1984. An intruder fatally beat him with a baseball bat. He was 81.

Pirates legend Willie Stargell and commentator Bob Prince, close friends, delivered eulogies at his memorial service.

“Playing baseball was an easier life than carrying bricks or cleaning windows,” Page said in the book “Voices From the Great Black Baseball Leagues,” published in 1975. “Baseball was something I had to do, really, because I didn't know how to do anything else.”

A scrappy, left-handed right fielder, Page was known for his ability to get on base. Often, his speed allowed him to lay down bunts and outrun throws to first.

Those bunts and his ability to hit a fastball allowed him to pummel legendary pitcher Satchel Paige, who in 1971 became the first former Negro leagues player inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y.

“ ‘I'm the worst pitcher in the world when you come up to the plate,' ” Page recalled his friend saying to him in the “Voices” book. “Why did I hit Satchel so easily? I don't know. You had some ballplayers I couldn't hit with a paddle or a broom.”

Page batted .335 for his career, with an average over .400 against white major league pitchers in barnstorming all-star games. In one exhibition game, Page claimed he hit two doubles to Babe Ruth's one. He said he collected hits off Jay “Dizzy” and his brother, Dean Paul “Daffy” Dean.

Of 300 members enshrined in Cooperstown, 35 are Negro Leaguers. Page is not one.

Among his former teammates are Gibson, Paige, James “Cool Papa” Bell, Oscar Charleston, William Julius “Judy” Johnson and “Smokey” Joe Williams.

Many of them played for the Grays and Crawfords in the early 1930s on what some consider to be the best teams ever. Page was one.

“Right on those two teams, you could have picked out maybe half of them who could have been Major League stars,” Page said in the “Voices” book. “I think I'm very lucky to be able to say that I played with all the great ballplayers, with and against them. ... I have tried to tell myself that had I played on a team that had fewer stars, I might have got more recognition. But how am I going to stand out on a team with Gibson, Satchel, Charleston, Bell? But I say, ‘By golly, I've got to be lucky to be on a team with men like that.' ”

Davis kept letters Bell wrote to her great uncle, promising to lobby to get Page into Cooperstown.

The Hall of Fame last inducted Negro League players in 2006, when it added a 16-member class that included John Preston “Pete” Hill, who grew up in Homewood. Hill died in 1951 and rested in an unmarked grave south of Chicago until the Grave Marker Project installed a headstone this spring.

As a child, Davis said she didn't know of Page's baseball exploits.

“The one thing about him is he didn't brag about anything. He didn't sit back and boast,” she said. “He was just Uncle Ted.”

Jason Cato is a Trib Total Media staff writer. Reach him at 412-320-7936 or jcato@tribweb.com.