Meet 'Bridges,' a computer that beats you at poker while decoding your genome

Bridges isn't the biggest, fastest or most powerful supercomputer in the world.

But the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center's newest monster machine is likely the biggest, fastest and most powerful supercomputer available to almost anyone.

Space on Bridges is open to research scientists studying biology, geology, archeology, economics and other social sciences who encounter enormous amounts of data but don't typically have the access or the know-how to analyze and process that data on a supercomputer.

"It's bringing supercomputing to the main experts from non-computing fields," said Nick Nystrom, principal investigator in the Bridges project and senior director of research at the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center

"Honestly, we're not afraid of the complexity."

Nick Nystrom, Senior Director of Research at Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center, works in the Bridges Supercomputer at the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center facility in Monroeville.

Photo by Andrew Russell

The amount of data generated in many research projects often outstrips the computing power of the machines available to those researchers, Nystrom said. That's the gap Bridges fills.

Bridges reduced the computing time from months to hours for Jay Apt, a professor of engineering and public policy at Carnegie Mellon University's Tepper School of Business and the co-director of CMU's Electricity Industry Center, and his graduate student, Michael Fisher. Apt and Fisher wanted to study the economic forces driving companies to install large batteries at their buildings to supplement their peak energy use and bring down the cost.

To do this, the pair collected a year's worth of electricity usage data for more than 600 buildings. The more than 18 million data points amounted to more than their personal computers could handle. They couldn't find space on other supercomputers until they found Bridges.

"The crux of it is it turns something that would takes months on my personal computer into hours on a supercomputer," Fisher said.

The pair finished their calculations on Bridges last year and published a paper in Environmental Science and Technology. Fisher said he hopes their work helps policymakers understand what drives companies to use batteries.

The Federal Reserve in Kansas City has signed up for space on Bridges to manage the country's finances. A group of meteorologists will use Bridges to predict where and when tornados and other devastating storms will strike this spring. Ruby Mendenhall, an associate professor of sociology and African-American studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, is heading a team of researchers who are using Bridges to comb through nearly 1 million books, articles and letters to find and understand the historical experiences of black women.

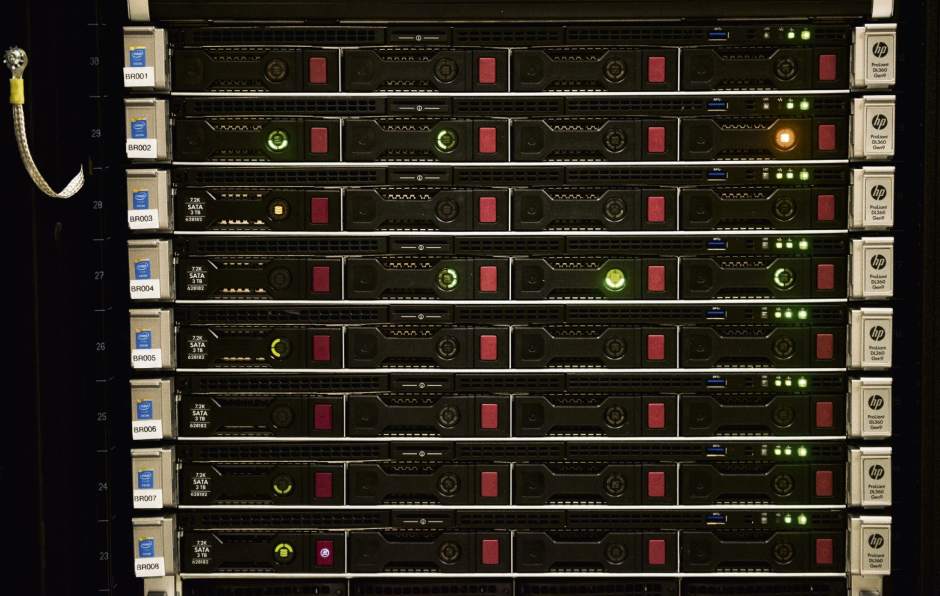

The Bridges project is housed at the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center facility in Monroeville.

Photo by Andrew Russell

And it's playing poker, powering Libratus, a pokerbot developed at Carnegie Mellon University that is challenging four of the top heads-up, no-limit Texas Hold'em players in the world in a rematch of the Brains vs. Artificial Intelligence tournament at Rivers Casino on Pittsburgh's North Shore.

"Extremely, extremely tough," Jason Les, one of the professional poker players challenging Libratus, said of the pokerbot.

After eight days and more than 40,000 hands played in the 20-day, 120,000-hand tournament, Libratus is up nearly 472,000 chips. Les said Libratus has improved its play and changed its strategy as the tournament has progressed. The humans, who get together after each day of play to study and strategize, took a risk with an unconventional strategy on Day 8 to try and throw Libratus off its game. It failed, costing the humans 200,000 chips and doubling Libratus' lead.

"Win or lose, it's proven to be a tough competitor," Les said before starting play Thursday.

Pro poker player Jason Les squares off against Libratus, an artificial intelligence program playing Heads-Up, No-Limit Texas Hold'em at Rivers Casino on Jan. 11, 2017.

Photo by Nate Smallwood

Bridges is powering Libratus from its home about 17 miles away in the basement of a sleek, all-glass office building tucked about a mile off Northern Pike in Monroeville. The supercomputer talks to Libratus, to the Pittsburgh Supercomputer Center's main office in Oakland and to its users across the United States over an Internet2 Network connection, essentially an internet only for academic and research purposes.

The Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center received $17.2 million from the National Science Foundation for Bridges. It cost $9.65 million to build the supercomputer. The remaining funding will be used to run it through November 2019.

Bridges went online last year and recently received an upgrade to add more computing power and storage.

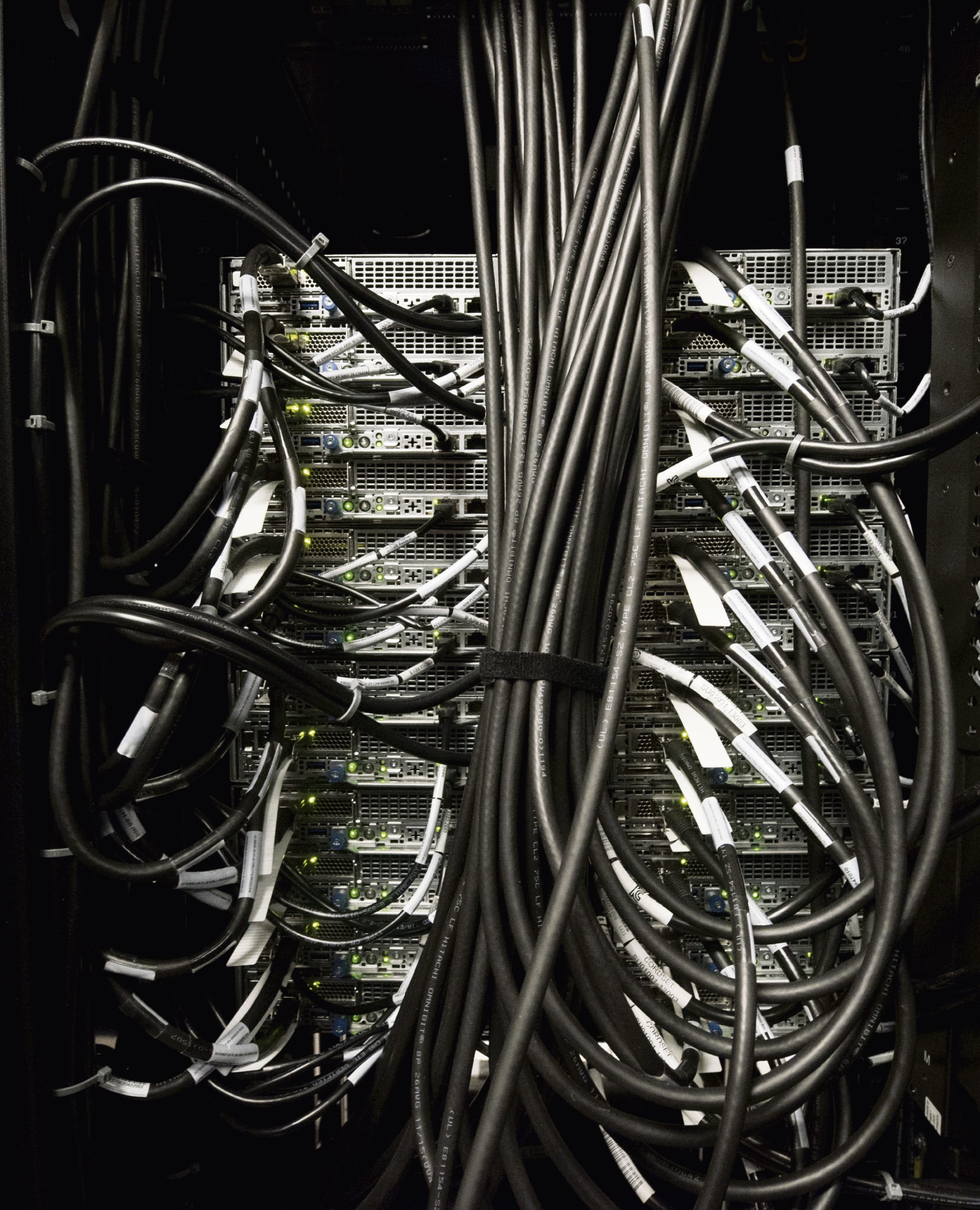

A supercomputer is basically several computers linked and networked together so seamlessly that it operates as one. There are more than 2,500 cables linking the components. Laid end-to-end, the cables would stretch about 4.5 miles.

Bridges lives behind a double-locked door. A keycard and access code is needed to open the door. It shares its room with other supercomputers, including one used by Uber to crunch its self-driving car data and Olympus, essentially a mini Bridges used by the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center's Public Health Applications group to study vaccine supply chains, pandemic modeling and more.

Humans don't visit often, Nystrom said. The Pittsburgh Supercomputing Centers staffs no one at the Monroeville building full-time and sends a technician only periodically for maintenance or to address problems. A robotic rover parked next to Bridges equipped with a camera gives virtual tours to people in the center's Oakland office and can investigate a warning light or other issue in a pinch, Nystrom said.

Bridges is 27 racks, each about 6 feet tall, of stacked computing equipment arranged in three rows. The supercomputer has 274 terabytes of random-access memory and 10 petabytes, equal to 10 million gigabytes, of storage. The computer is about 29,000 times as fast as a top-end laptop and has enough storage for 20,000 years of mp3 music files.

Bridges sounds like a boiler room. Vents in the floor pump in refrigerated air that gets sucked into the computer by hundreds of tiny fans to keep the machine cool. It feels 10 degrees cooler at the front of Bridges — known as "cool alley" — than in between the racks — known as "hot alley."

Bridges features three types of computing options, called nodes, with three memory sizes: regular, large and extreme. Regular memory nodes have 128 gigabytes of RAM, about eight times the computing power of a high-end laptop. There are 800 regular nodes.

Libratus is running on 600 to 700 of those nodes, Nystrom said. A small subset of those nodes makes decisions while playing. The rest work toward improving Libratus, studying hands, patterns and game play to make it a better poker player.

Large memory nodes have three terabytes of RAM, and Bridges has 42 of them. For perspective, Watson, the IBM supercomputer that beat two top Jeopardy champions, had 16 terabytes of RAM.

Scientists crunching data from genetic sequencing use Bridges' large memory nodes. If a scientist wants to analyze genetic data from several genomes, like bacteria in the human gut or in the soil, that work may spill onto Bridges extreme memory nodes, featuring 12 terabytes of RAM. Bridges has four of those because few projects reach that size or complexity, Nystrom said.

Nystrom said he sees the day coming when doctors working in a hospital can access Bridges to run tests and analyze samples nearly in real time. A doctor could take a biopsy, ask a patient to wait 15 minutes, do the sequencing and let them know what's going on.

"Rather than have them be in this period of fear for days or weeks waiting for lab results," Nystrom said. "That's part of what we're trying to enable, just accelerating the time to discovery. ... We need to know things now."

Aaron Aupperlee is a Tribune-Review staff writer. Reach him at aaupperlee@tribweb.com or 412-336-8448.