Schools, teachers attempt to tackle achievement gap in Western Pennsylvania

Western Pennsylvania's school administrators and teachers are working to improve outcomes for all students in schools that are becoming segregated by race and income. Black students are disproportionately represented in poor, urban areas, and white students dominant in suburbs.

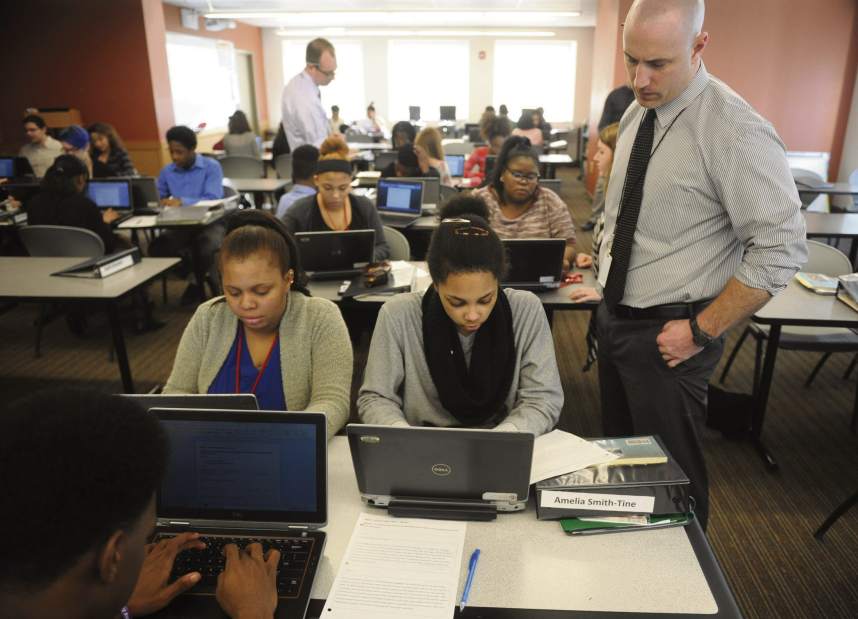

“We can't change anybody's race,” City Charter High School CEO and Principal Ron Sofo said. “We need to create more culturally responsive learning environments that are inclusive of all of our students.”

Black students lag behind their white peers on several metrics gauging their likelihood of success. Blacks demonstrate higher rates of absenteeism, suspensions and dropouts, and lower rates of enrolling in advanced or honors courses, going on to post-secondary education and finding family-sustaining jobs.

Mark Brentley, a former Pittsburgh school director, worries that racial disparity in schools contributes to a “permanent underclass” for blacks.

More than half the students in city schools are black, and the district hired consultants to train faculty and staff in “understanding institutional racism,” Superintendent Linda Lane said.

“We've had a lot of staff trained to better understand this thing we call race, the impact that it can have on children of our schools, and what can happen when we do not admit that all of us have biases,” Lane said.

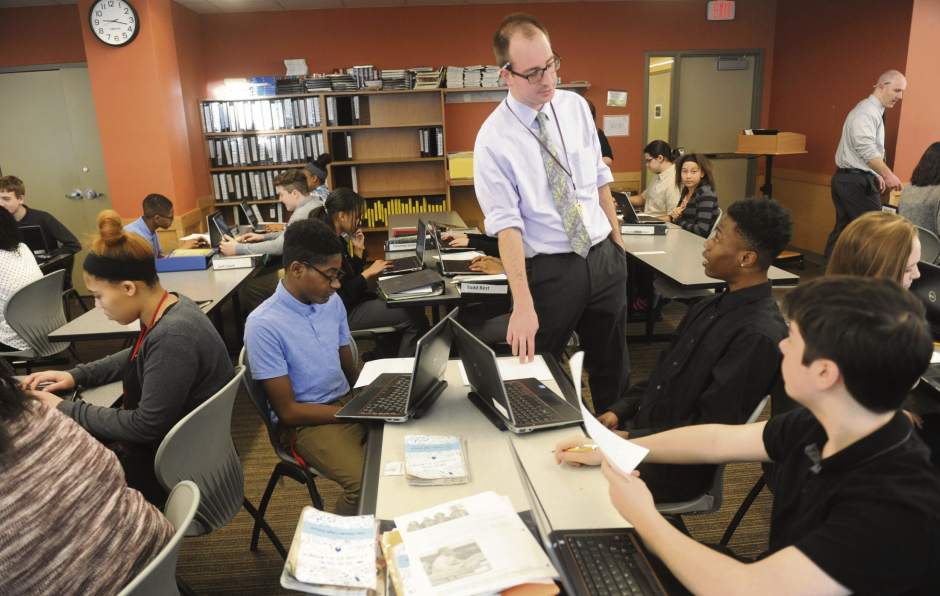

Across the region, efforts to close achievement gaps between white and black students range from rolling out broad initiatives to rethink curriculum and how it depicts minorities, to getting teachers to pay closer attention to which students they call on in class.

“We don't have a ton of diversity, but very rarely is it a negative thing,” said Heather Bigney, principal of Grandview Upper Elementary in Highlands School District.

The school in Tarentum is predominantly white, but it's predominantly low-income. It runs a conflict resolution program called Second Step that promotes tolerance and empathy. Bigney said her teachers strive to make children feel safe and recognize differing learning styles.

“Kids in poverty learn differently,” Bigney said. “They hear less words growing up, they communicate less, they have less experiences — if they struggle financially, they don't have the money to go to a play or go to the beach.”

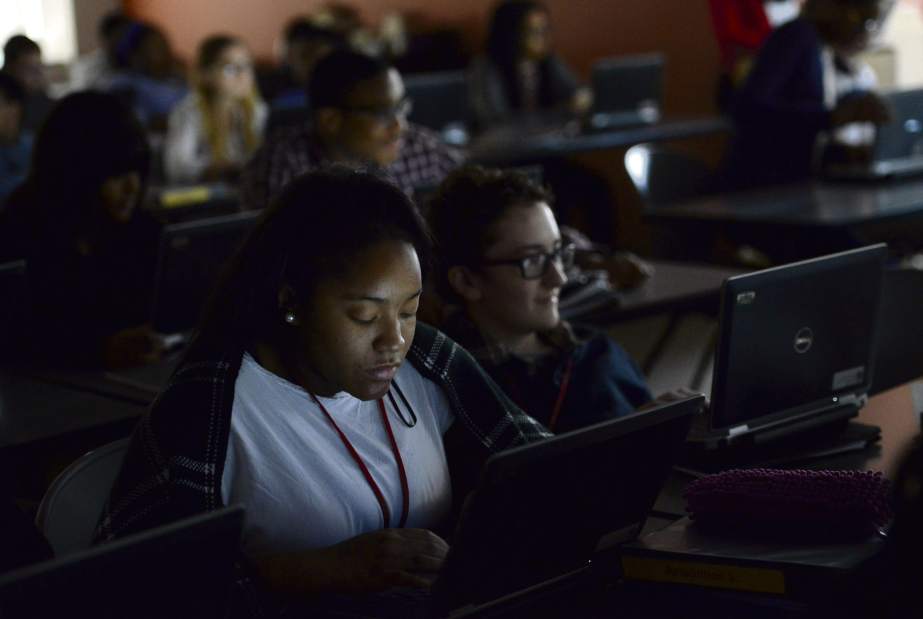

At City Charter High School, a relatively integrated school in Downtown Pittsburgh, students take a cultural literacy class that draws on literature, history and current events to stimulate discussions around racial issues in the region.

Natasha Lindstrom is a Tribune-Review staff writer.