Wayward record of Pittsburgh's early years recovered by archivist

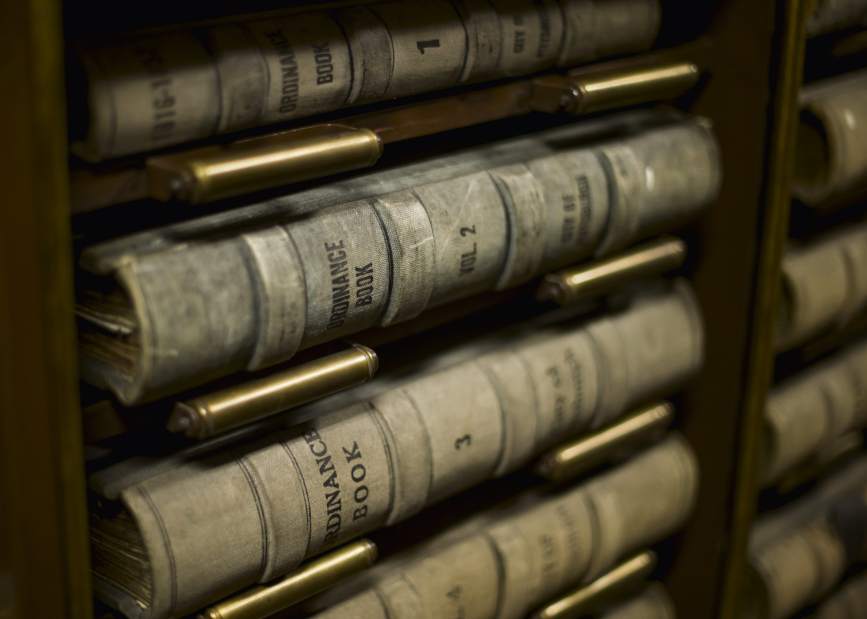

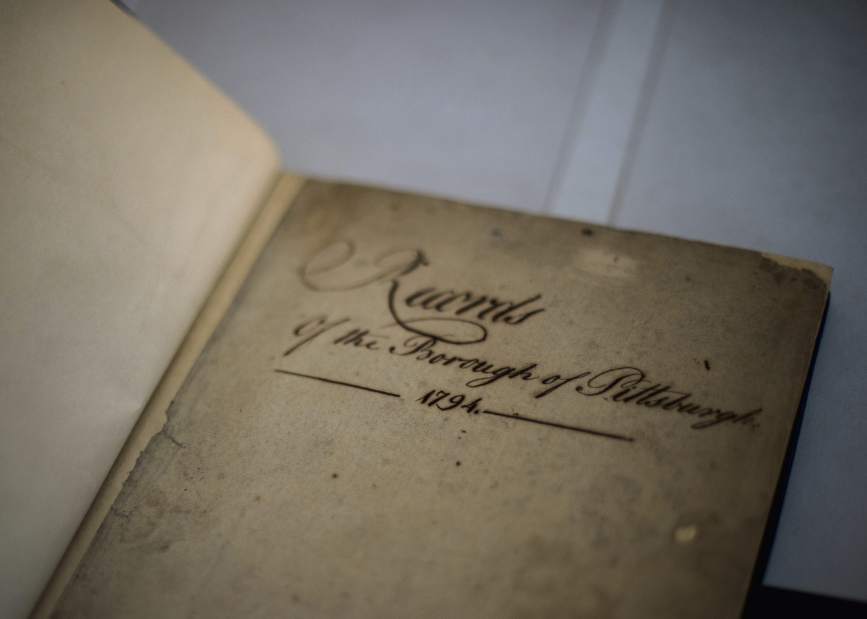

For 122 years, a book containing the only official record of Pittsburgh's first nine years as a borough resided in Philadelphia.

Nick Hartley, 28, said someone made off with the leather-bound volume about 1895, and in 1912 someone sold it for $150 to the Pennsylvania Historical Society.

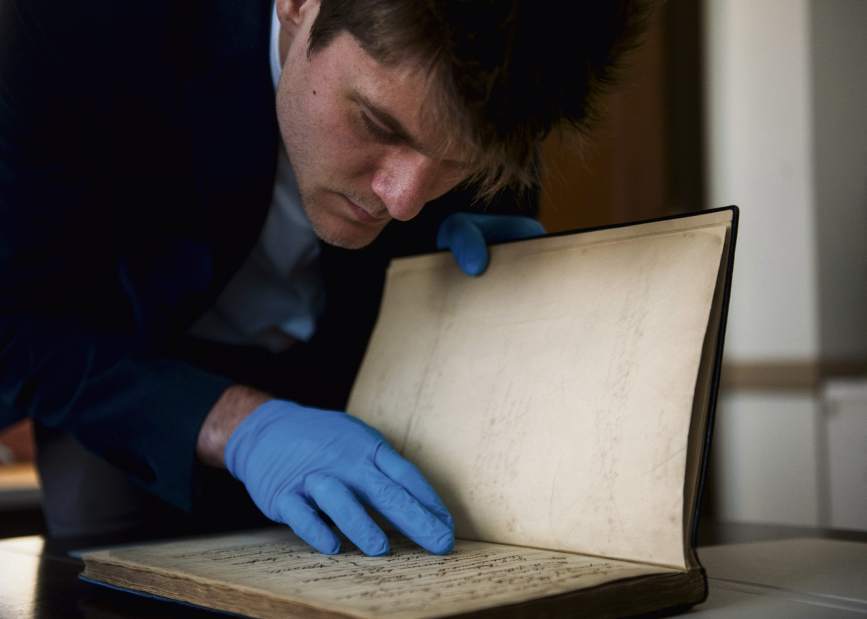

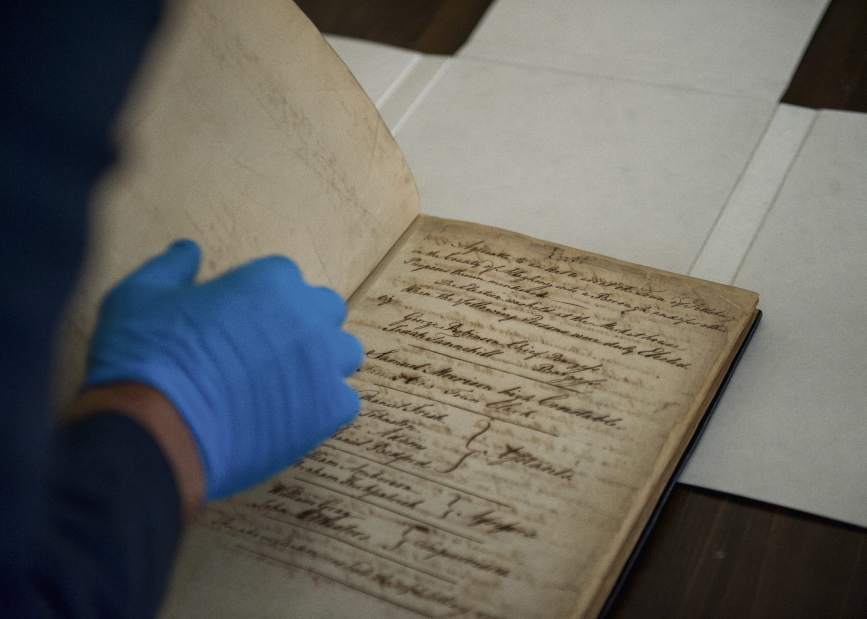

He was elated May 22 — more than a century later — to recover the book containing the fledgling government's minutes from 1794-1803.

“I drove to Philadelphia and got it,” he said.

Hartley, Pittsburgh's first historical document archivist, is mining history from dusty corners in government offices across the city.

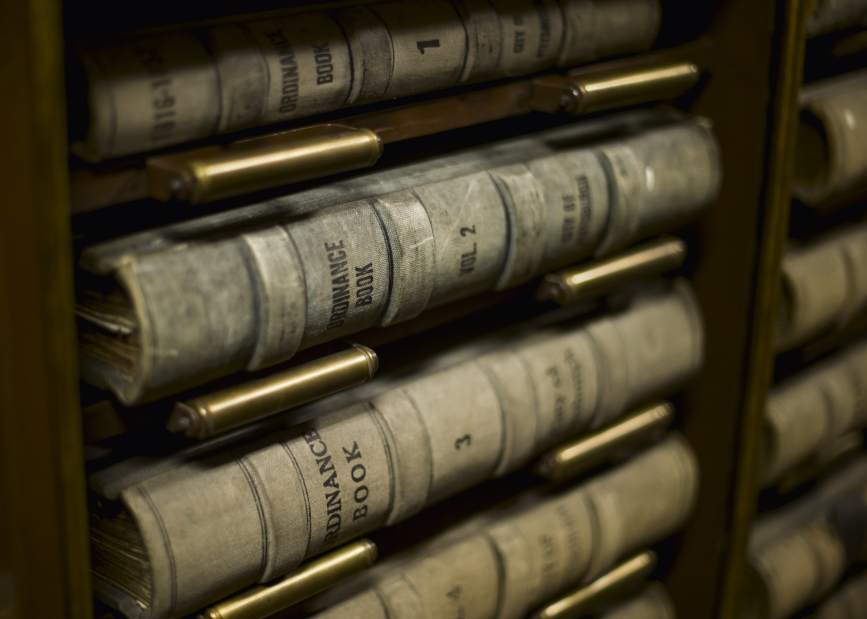

He has uncovered legal records containing rare 19th century information about Pittsburgh residents, drawings of city school buildings from the 1920s and maps that document city growth from its beginnings as a frontier outpost.

One of the first things he learned after arriving in August was the existence of the old borough minute book. His former boss at the Heinz History Center in the Strip District — Matt Strauss, the chief archivist — had discovered it accidentally while browsing online Pennsylvania Historical Society records.

Pittsburgh City Council learned it was missing in 1895 and ordered the city clerk to find it, according to a council resolution from that year.

“They didn't find it,” Hartley said. “We now know, 122 years later, that it was taken in 1895, and I guess 17 years later sold to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.”

Nobody knows how it was removed from a council vault where records are stored, or how it arrived in Philadelphia.

The historical society gladly returned it at no charge after confirming Pittsburgh could store it, according to Charles T. Cullen, the society's interim president and CEO.

“We thought the noble thing to do, and the right thing to do, and the moral thing to do was return it to its rightful place,” Cullen said.

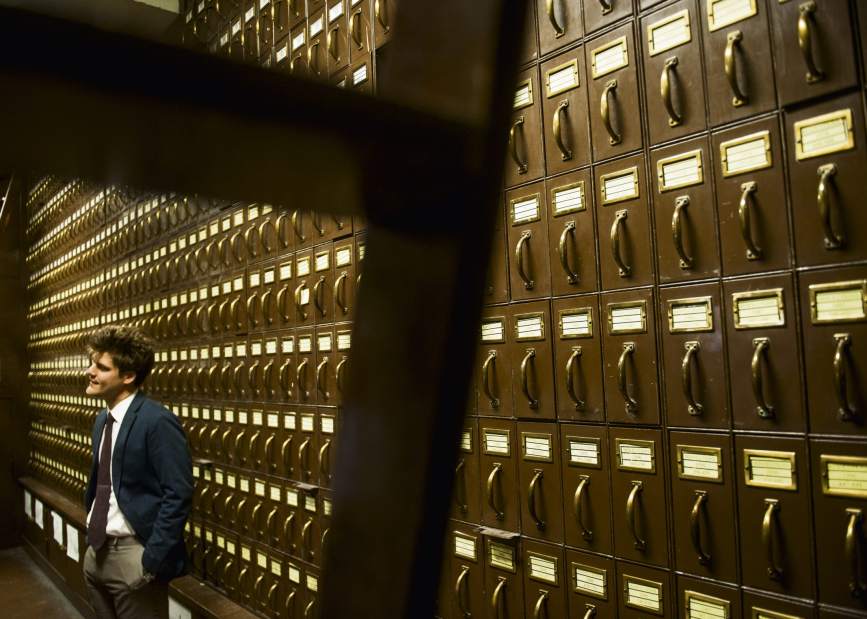

Hartley spends his days visiting city departments and searching through boxes of time-worn documents.

“The city has a lot of property, and if I want to know where things have been hiding for so long, I'm going to have to just visit the places and ask around,” he said. “With (the Department of Public Works), in particular, they have about 19 different offices in various divisions, and I visited each one.”

The book is the most exciting item he has recovered.

The second best find was hundreds of boxes filled with board of viewers' reports from Pittsburgh and former Allegheny City containing testimony from residents complaining about street improvements.

One of the complaints was from Pittsburgh coke-and-steel tycoon Henry Clay Frick.

Frick associates testified in 1912 that the widening of Cherry Alley devalued the Frick-owned block between Fifth and Oliver avenues, where he would eventually build the Union Trust Building. Frick was seeking $172,000 in compensation.

The reports contain personal information about city residents and property descriptions that cannot be found anywhere else.

“In most cases, the stories you can find in here would be totally inaccessible,” said Hartley, noting that the records were stored in an obsolete Department of Public Works office in Oakland.

Hartley found two books containing blueprints of school buildings dating from 1920 to the 1930s and volumes containing property maps that document the city's growth from its early days.

His next job, after surveying city records, is to craft a document retention schedule. He plans to advocate for creating a repository that would be open to the public.

Former City Councilman Patrick Dowd, who sponsored legislation in 2012 that led to Hartley's hiring, said he was ecstatic the city is finally working to preserve its historic records.

“This should have been done a long, long time ago,” said Dowd of Highland Park, a former history teacher and now the executive director of Allies for Children, a child advocacy group. “I feel badly that it took me that long to figure out that we needed to do it.”

Bob Bauder is a Tribune-Review staff writer. Reach him at 412-765-2312, bbauder@tribweb.com or via Twitter @bobbauder.