Postcards: Hotelier in Egyptian town of Abydos holds dear Temple of Seti I's powers

ABYDOS, Egypt — The ancient Temple of Seti I is slightly elevated above this sleepy farming town backed by mountains.

This once was a sacred spot, a center of cult worship of the god Osiris, judge of the dead and king of the Underworld.

Today, the L-shaped temple is a cooling escape on a 100-degree day.

“I want to tell you something about this temple,” says a local hotelier, who calls himself “Horus,” after one of ancient Egypt's best-known gods. Unlike that falcon-headed deity, this modern Horus is 57, bald, and wearing an ankle-length cotton gown called a galabiya.

“This temple is built for healing,” he confides conspiratorially. “That is why when anybody from ancient Egypt entered this temple, they felt something different inside. There is also a way to enter the temple so that the energy cooperates with your body.”

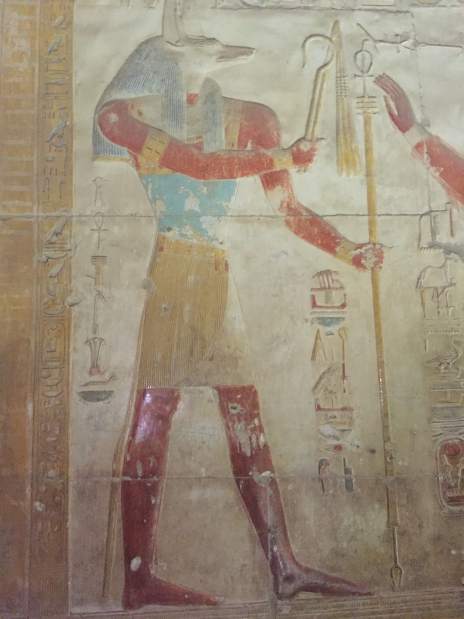

Pharaoh Seti I (1294-1279 B.C.) built the temple to celebrate many gods, and it became a place of pilgrimage. The delicate raised wall reliefs — the striking work of some of the best ancient sculptors — retain their brilliant blues, reds and yellows.

Seti I died before finishing the temple; his son, Ramses II (1279-1213 BC), completed it in a different style, cutting images into the stone instead.

High up on one wall, near a column, some mysterious hieroglyphics look like no others.

One symbol resembles a helicopter; some people believe a second represents an army tank or a boat. A third is described as a submarine or a spaceship, a fourth as a jetfighter.

To some people, these prove that advanced technologies or aliens mysteriously appeared in the ancient world. Or they prove the fabled city of Atlantis existed. Or that time-travel occurred.

“No, no … that is not right,” says Horus, echoing Egyptologists' explanations of the strange symbols. “It was two cartouches, one for Seti I and one for Ramses II, they are put on top of each other … so it is the mix-up of two cartouches.

“There was no aluminum or metal usage at that time, only copper.”

But he does insist that the ancients were more advanced “in magic … in spirituality and astronomy and life after death” than their everyday technology suggests.

Horus got his name as a boy from a British woman who settled here in 1959 and called herself Um Seti, or “Mother of Seti.” She believed she was Seti I's wife in a previous life.

“I had a dream and I explained the dream (to her), and she said, ‘Oh, you are Horus,' ” he explains.

This modern Horus co-owns the 86-room House of Life Hotel here, its façade brightly painted with ancient symbols and two faux obelisks flanking its steps.

He calls it a health-and-healing center: “We follow all of the ancient Egyptian methods of treatment and healing,” including incense, perfumed oils and music.

“Groups come here to take courses.” Others meditate in the temple: “They go into a trance … and we interpret the meanings of their visions.”

Inside the temple is a room where some visitors would “sleep for a week, and if they had any diseases, they would get cured,” he says.

He plans to open the hotel in October, when Egypt's tourism season starts anew; he plans “a big celebration … like the days of Osiris,” in May, with a long pilgrimage from the temple to the royal burial grounds and other parts of the temple complex, the walk taking the shape of a pyramid.

He hopes for 5,000 visitors, mainly people who have taken his healing courses over the years, and expects officials to open the temple for them at night.

The pilgrimage will follow a special pass between the mountains where pharaonic Egyptians “believed the energy comes from — the Stargate, as they called it in ancient times,” he says.

It will take “about 15 days … the men (will) shave their heads” and carry a “solar boat” that Horus intends to build.

The House of Life and its owner are oddities in this town, where most people till the land and camel-riding tourist police guard the temple complex.

“The locals, they say we are insane,” Horus concedes — but some still believe in the ancient powers, such as “women who can't have children. They go to the temple and afterward they wash up in the sacred pool, in the hopes of getting pregnant.”

Asked how he would treat a reporter's broken ankle, he adds: “We would take you to the mountain and treat you with sand, seven times, and you will walk out like a horse.”

Betsy Hiel is the Tribune-Review's foreign correspondent. Email her at bhiel@tribweb.com.