Conservation practices of certified Fairfield Township tree farm on display

Fairfield, Westmoreland County tree farm tour

Tour set for 9-30-17

Sometimes you have to put up with a little dead wood — if you live on 50 acres, about half of it covered by trees.

Rus Davies learned that the hard way when he discovered a pest was killing the ash species that is scattered among his five large stands of trees in Fairfield Township.

“You have to look for a D-shaped hole in the bark,” Davies said, pointing to the sign of an emerald ash borer invasion that has left a tree bordering his driveway denuded of foliage. Over the past several years, he's counted 43 more dead ash trees in the roomy backyard between his ranch house and pole barn, and he estimates at least 60 others have fallen victim to the beetle.

Davies is inviting the public on a free tour of his property Saturday to learn how he's managed it, under the auspices of the Pennsylvania Tree Farm Program and the American Forest Foundation, and how he's dealt with crises like the ash borer.

Seeking advice from a forester, Davies concluded the lifeless trees will have to stay where they are for now. He explained the lumber in the stricken trees isn't worth much, so it would be prohibitive to have a logger make a selective cut of only those trees.

“With the ash, the mortality happened so fast,” he said.

At the same time, Davies isn't keen on felling more valuable neighboring trees just to make the project feasible. He's interested in an eventual “commercial cut” of some of his trees, but not just yet, he said.

A previous “salvage” cut made more sense. He harvested 80 oak trees on his property that were damaged by gypsy moths but still had value as timber. The damage occurred even after he signed up in 1990 to have the county spray 36 of his acres by helicopter to help control the insects.

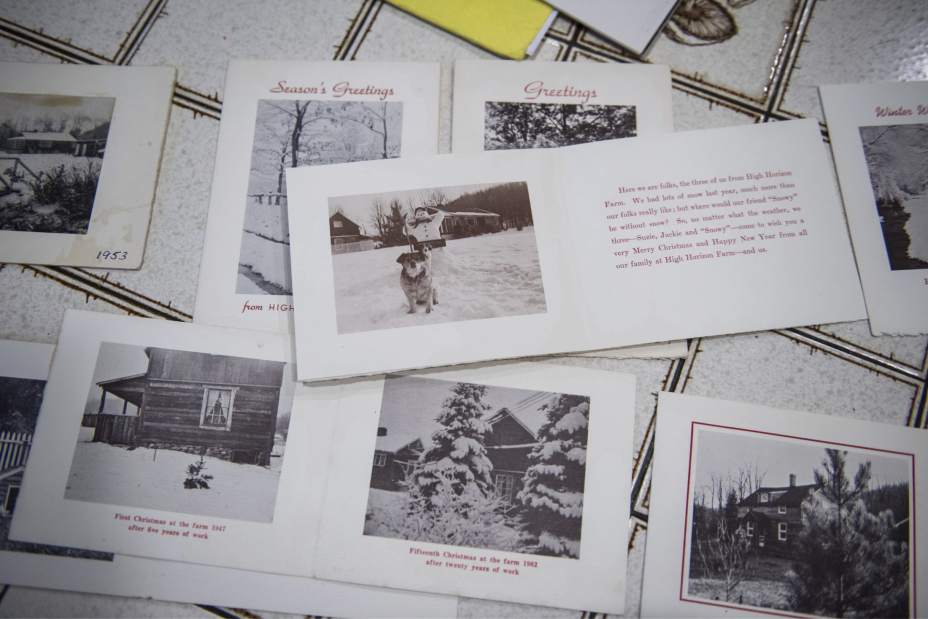

Davies is a careful steward of his rural spread, nestled alongside the Chestnut Ridge and dubbed High Horizons.

There are certain things he can't do with the expansive property, such as subdivide it, develop a commercial enterprise on it or host a loud music festival — according to the terms of a perpetual conservation easement enforced by the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, from which he purchased the acreage in the late 1970s.

He agreed to a management plan for his wooded property and periodic inspections of it when he registered it as a certified tree farm under the Pennsylvania Tree Farm Program in the 1980s.

Tony Quadro, a forester and assistant district manager of the Westmoreland Conservation District, said Davies' active attention to his tree farm has allowed it to retain certification for the past three decades.

“In the mid-1970s, there was a push to have everybody in the tree farm program. There used to be somewhere around 40 to 50 (tree farms) in the county,” Quadro said. “There are fewer of them now because they made the standards and practices a little more stringent. The feeling was, even though they're fewer in number, they're better tree farms.”

Davies noted his management plan balances sustainable development of marketable timber with a desire to protect the wildlife that roams his property.

“We've got a lot of turkey and deer and the occasional black bear,” he said. He's also sighted red foxes and a bobcat.

On some acreage where trees have sprouted in former fields, he noted, “We have a lot of early succession (tree) species, crabapples and hawthorn. That's good for wildlife, but not for commercial timber.”

Gradually, those trees will be “overtopped” by more valuable hardwood species such as cherry, oak and hickory, Davies explained.

There is an economic advantage to having a wooded area of at least 10 acres recognized as a tree farm, according to Tom Fitzgerald of West Wheatfield, Indiana County, who chairs the state Tree Farm Program for 10 counties in Southwestern Pennsylvania. The resulting timber will be more marketable, he said, noting some companies “insist that their publications be printed on paper made from certified wood.”

A native of suburban Pottsville, Davies learned to love the natural setting of his Fairfield home when a new job brought him to Southwestern Pennsylvania in the late 1970s.

“It's inspired my conservation ethic,” he said of the farm.

Though their methods may differ, Davies is following at least part of the intent of the property's former owner, Mary Kolb, who posted the grounds as a wildlife sanctuary before willing it to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy. Kolb was executive director of the Frick Educational Foundation in Pittsburgh and was visited at High Horizons by famed environmentalist Rachel Carson.

Davies noted Carson's classic “Silent Spring” was required reading in his youth.

Davies is a board member of the Westmoreland Woodlands Improvement Association, which is organizing the tour of his tree farm. The group's mission is to encourage good management of woodlands for aesthetics, timber, water quality and control, wildlife habitat, plant propagation and recreation.

In the past, Davies harvested some of his trees to heat his home, but he now uses propane. “I got tired of cutting seven cords of wood a year,” he said.

Jeff Himler is a Tribune-Review staff writer.