Fred Rogers' legacy continues through company he started

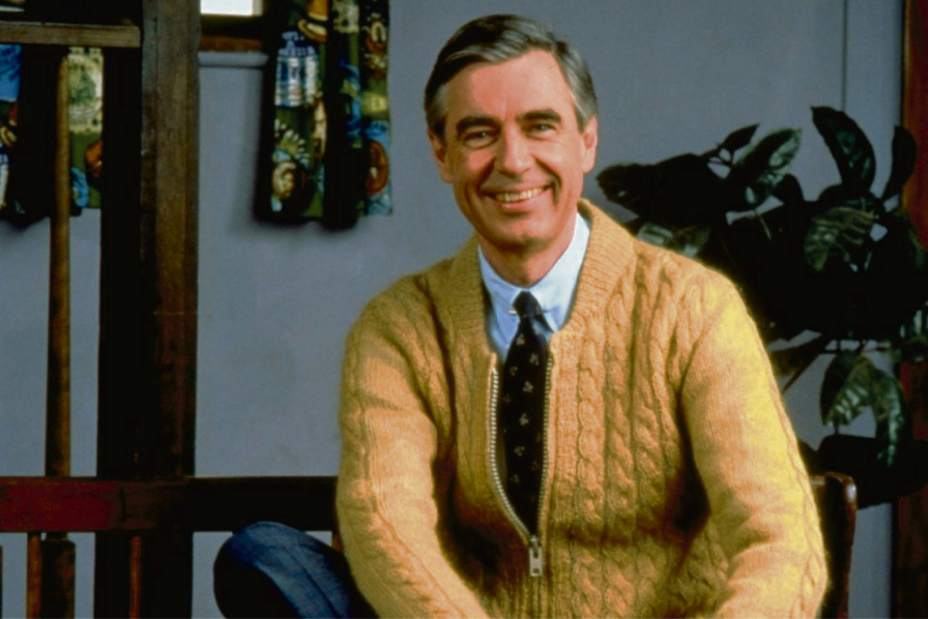

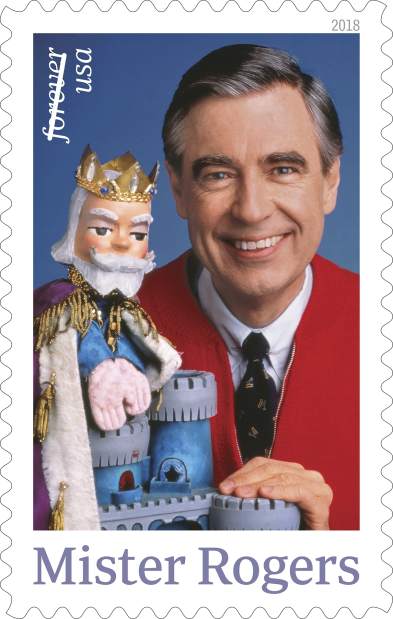

When Fred Rogers died in 2003, some wondered how the children's television production company he started more than three decades earlier would go on.

Just fine, it appears.

Although the last reruns of "Mister Rogers' Neighborhood" aired in 2008, the company that he built continues to thrive in children's television and digital media.

A pair of animated TV shows, a live-action show, a variety of licensed items — toys, bedding, clothing, books, DVDs and special apps — round out the product line. The Fred Rogers Co. listed revenues of $20.2 million and assets of $28.2 million on a federal tax filing for 2016, the most recent year for which figures are available.

That's a long way from the $30-per-episode budget Rogers had to work with in the 1950s for "The Children's Corner," his first entry to children's TV at WQED Pittsburgh with host Josie Carey. But it's nowhere near the $130 million a year in revenues logged by the Sesame Workshop, the nonprofit behind Sesame Street.

But Rogers was never in a race to keep up with anyone.

This day in #PGHistory : We are introduced to our favorite neighbor, as "Mister Roger's Neighborhood" premieres nationwide. (1968) pic.twitter.com/4jaHhg6QH5

— Pittsburgh Clothing Co. (@PGHClothingCo) February 19, 2018

And those entrusted with continuing Rogers' company upon his death took the same careful, measured approach. Even the motto of the new iteration of Family Communications Inc. — the nonprofit company Rogers founded in 1971 — reflects the importance of protecting the company that today bears his name: The legacy lives on, it states.

Pittsburgh is Mr Rogers' Neighborhood. https://t.co/N7g36gc8m8

— bill peduto (@billpeduto) February 19, 2018

Bill Isler led the company from 1983 until he retired at the end of 2016. He said its board carefully weighed its resources and vetted the research on childhood development before opting to create an animated series based on one of Rogers' puppets — Daniel Striped Tiger — as its flagship enterprise. The company joined forces with Angela Santomero, a student of Rogers who co-produced the Blues Clues children's program on PBS, to execute the new project.

After an intensive development, the half-hour show that features work by the Animated Mind Story Group debuted in 2012. When production wraps up this year, it will have an archive of 105 half-hour segments.

Paul Seifken joined the company in 2013, after working as a high school English teacher and serving as director of children's programming at PBS. He took the helm after Isler's retirement. Daniel Tiger builds on the kind of warm, caring approach Rogers brought to talking with young children about feelings, he said.

Rebecca Dore, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Delaware who studies developmental psychology and how children learn from media, said there are a lot of similarities between Mister Rogers' Neighborhood and Daniel Tiger's Neighborhood — despite format differences.

"Both Mister Rogers and Daniel Tiger are warm, relatable characters. Both use a lot of songs. Both focus on pro-social behavior and emotion regulation strategies," Dore said.

In addition to Daniel, the company has launched Peg+Cat, an animated math-based program aimed at 3- to 5-year-olds, and the Odd Squad, a live-action show aimed at 6- to 8-year-olds, again using math to solve problems.

Recently, the company partnered with Jesse Schell of Schell Games, a Southside-based game developer from Carnegie Mellon University, to design apps that drive home the same lessons.

"I think Fred would have liked Jesse Schell," Isler said. "Fred never wavered in his belief in the importance of childhood and that we had to make television and all technology appropriate for children. When new technology came in, Fred wanted to know what was appropriate and why."

In addition to its programs and licensing agreements, the company partners with local nonprofits and organizations to funnel its research back into the community in projects such as summer camps and teacher training.

The money that flows into the company from licensing and programming all goes back into the mission, Seifken said.

"We're a nonprofit, and PBS is our broadcaster," he said. "Unlike a commercial network that would pay the entire cost of production, PBS pays a fraction of that. So, a large percentage of cost of production falls on the producer. We need to find multiple source of revenue. There's some underwriting revenue and some foundation support.

"It is an interesting puzzle we need to put together," Seifken said.

Debra Erdley is a Tribune-Review staff writer. Reach her at 412-320-7996, derdley@tribweb.com or via Twitter @deberdley_trib.