https://archive.triblive.com/local/westmoreland/jehovahs-witnesses-legal-battles-in-western-pennsylvania-laid-groundwork-for-religious-freedoms/

Jehovah's Witnesses' legal battles in Western Pennsylvania laid groundwork for religious freedoms

Submitted

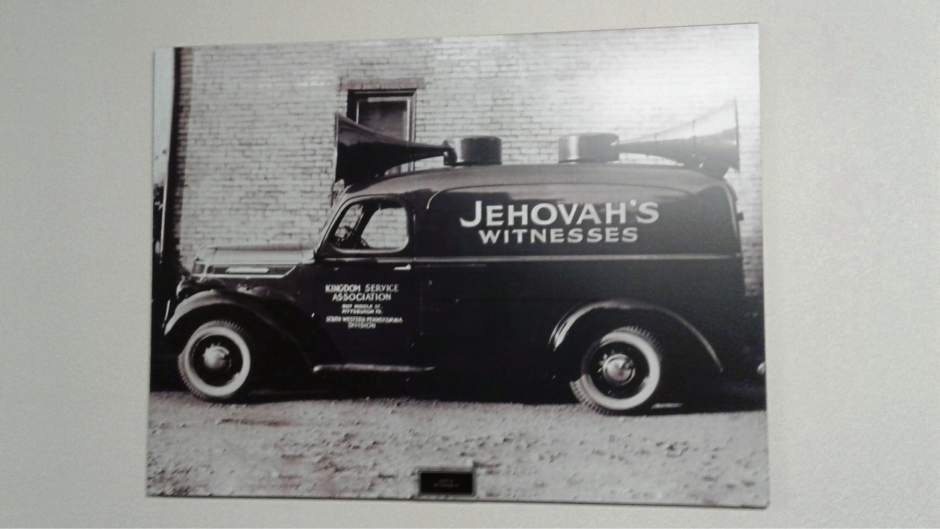

A Jehovah's Witnesses 'sound car' used in evangelistic campaigns in the 1930s. The speakers helped broadcast the religious sect's teachings and upcoming meetings in Greater Pittsburgh.

In 1939, the tranquility of a Palm Sunday morning in Jeannette was broken by the arrival of more than 100 people from out of town.

They parked their 25 cars outside the city limits and set up a makeshift headquarters at a local gas station with a public telephone — just in case there was any trouble.

The people, who called themselves Jehovah's Witnesses, descended on Jeannette starting about 9 a.m. — as residents were preparing for Palm Sunday services — and began knocking on doors. It didn't take long for the phone to start ringing at the police office, according to the court record.

In total, 21 Witnesses were arrested for violating a 40-year-old city ordinance requiring solicitors to obtain a permit before going door-to-door. Among them was a man named Robert L. Douglas.

Facing a fine of up to $100 or a jail sentence of up to 30 days, Douglas appealed his conviction, arguing that the city's permit requirement was an unconstitutional violation of his First Amendment rights. By 1943, the appeal had made its way to the Supreme Court under the name Douglas v. City of Jeannette.

The wave of Palm Sunday arrests did not dissuade the Witnesses from returning to Jeannette the following year. Buoyed by years of hostility from local authorities and the general public, Jehovah's Witnesses were nothing if not tenacious in their approach to evangelism. This time, eight people, including Robert Murdock Jr., were arrested.

Their legal challenge, titled Murdock v. Pennsylvania, arrived at the Supreme Court at the same time as the Douglas case from the preceding year. In May, the justices released four decisions, consolidating 13 cases, pertaining to the rights of Jehovah's Witnesses to proselytize and disseminate literature.

Twelve of the 13 cases went in their favor — an unprecedented victory for the small, beleaguered sect — making that day 75 years ago a seminal one not only for Jehovah's Witnesses but also for anyone who invokes the First Amendment guarantee of religious freedom, experts say.

Shaping religious freedom laws

The Jeannette cases, especially Murdock's, helped shape the body of law that continues to define the scope of religious free exercise to this day, said Holly Hollman, general counsel of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty.

“In the development of religious liberty law, the Jehovah's Witnesses have had a disproportionate impact compared to their relatively small size,” Hollman said. “These cases stand for many propositions that are still important for religious freedom.”

The Witnesses are credited with winning at least 30 major cases involving religious liberty issues since 1938. As recently as 2002, the Supreme Court, in Watchtower Bible & Tract Society of N.Y. Inc. v. Village of Stratton (Ohio), reaffirmed 8-1 its finding in Murdock that permit requirements for religious door-to-door canvassing violate the First Amendment.

“(Murdock) has modern viability; it's not just a relic of history,” said attorney Paul Polidoro of Watchtower Legal. “The Supreme Court made it crystal clear in 2002 that it's still controlling law.”

Hollman said that in the 1930s, Jehovah's Witnesses developed an assertive legal strategy to match their assertive evangelistic practices — practices that were often misunderstood and challenged, even attacked.

“You're more likely to have a clash with government policy if your practice is unfamiliar,” she said. “Clashes between people who are practicing their religion and the government most often come from religious minorities.”

Those clashes turned violent in 1940, as Jehovah's Witnesses came under attack for refusing to say the Pledge of Allegiance or salute the American flag. Bolstered by the Supreme Court case Minersville v. Gobitis, which upheld a Schuylkill County school district's flag salute requirement, communities resorted to violence against Witnesses and their Kingdom Halls.

“There's no question that between the 1930s and '40s, there were people trying to make it appear that our ministry was criminal, illegal, even subversive,” said Don Peters, an elder with the Greensburg Kingdom Hall.

Peters, 79, of Delmont said local child Witnesses who were expelled from public schools for not saluting the flag ended up going to an ad hoc Kingdom School in the village of Gates in German Township, Fayette County.

Meanwhile, adult Witnesses were scorned by communities for their alleged lack of patriotism and for confrontational evangelistic methods, including the use of record players and “sound cars” that broadcast the message in neighborhoods.

“There were several that were arrested and put in jail,” Peters said. “Several I talked to said they used to take their toothbrush with them (witnessing) because they knew they'd spend the night in jail.”

‘An uphill battle'

The outbreak of violence in the early 1940s was “one of the worst episodes of religious persecution in U.S. history,” said Shawn Francis Peters (no relation), author of “Judging Jehovah's Witnesses: Religious Persecution and the Dawn of the Rights Revolution.”

“Religious minorities always face an uphill battle in this country, even though this country was founded on religious liberty,” he said.

Peters begins the book by recounting an anti-Jehovah's Witnesses riot in Imperial, Allegheny County, in the summer of 1942. The incident, documented by the American Civil Liberties Union at the time, resulted in several Witnesses being beaten, and their property damaged, when they refused to salute the flag.

Such incidents were repeated in dozens of communities as the country, preparing to enter World War II, feared a “fifth column” of homegrown Nazi sympathizers, he said. By the time the Supreme Court overturned its controversial Minersville decision in 1943, the violence had died down.

Peters calls Jehovah's Witnesses the “unlikely heroes” of the 20th century fight for civil liberties by minorities in the United States — their record of litigation before the Supreme Court being matched only by the NAACP.

“These cases really do matter (because) they're helping to get civil liberties in the forefront of the (Supreme) Court's attention,” he said. “The rights revolution really starts in Jeannette and other places like it.”

Stephen Huba is a Tribune-Review staff writer. Reach him at 724-850-1280, shuba@tribweb.com or via Twitter @shuba_trib.

Copyright ©2025— Trib Total Media, LLC (TribLIVE.com)