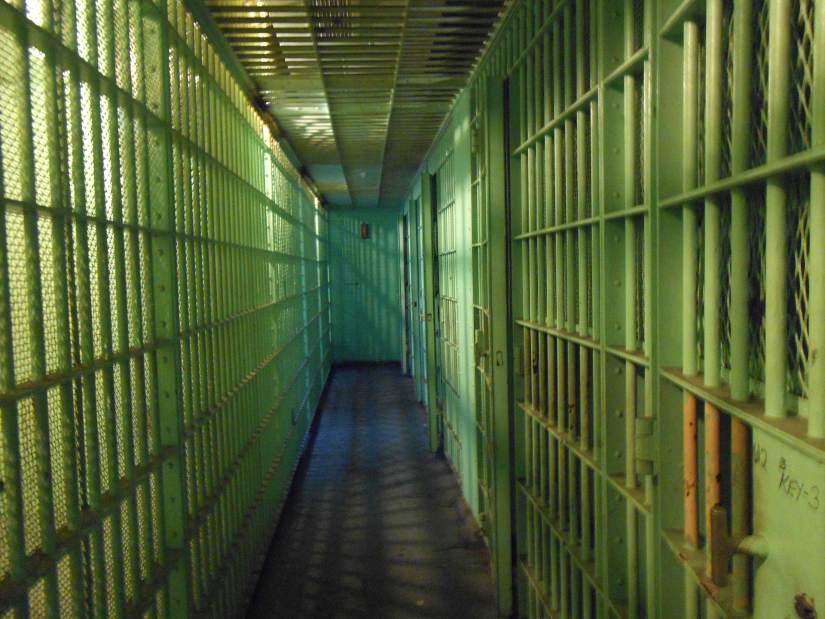

Nearly 20,000 state prison inmates are set free every year in Pennsylvania, yet records show that as many as half of them are locked up again within three years.

But a new study, conducted by a University of Maryland researcher for the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, may show the way to lower recidivism rates.

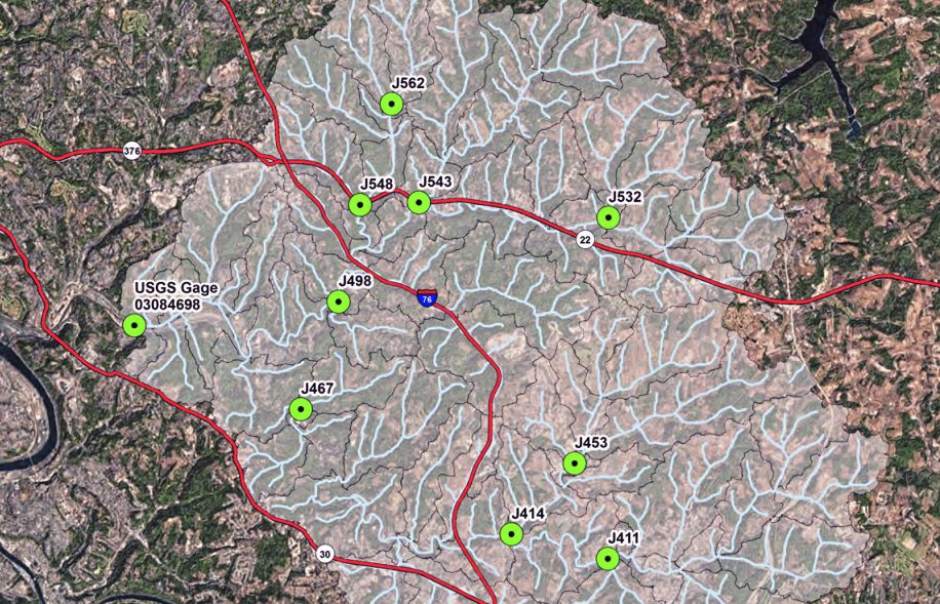

Officials randomly divided 647 inmates from Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and Harrisburg who volunteered for the study into two groups. Those in one group were paroled to their home city; those in the other group were dispersed to one of the other two cities.

Results of the two-year study by researcher Kiminori Nakamura defied long-held common wisdom, said Brett Bucklin, director of planning, research and statistics for the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections.

Time-honored theories hold that inmates who maintain community ties have a better chance of staying out of prison once they are released. But the Pennsylvania study found that those paroled to urban communities other than their own had lower recidivism rates than those who returned to their hometowns.

Bucklin said a 7 percent reduction in recidivism among the out-of-town parolees is statistically significant and could lead to cost savings in the state's parole budget, which is about $200 million per year.

Although Pennsylvania's prison population has declined from a high of about 52,000 in 2010 to about 48,300 now, officials recorded a 46 percent increase in parole violations — many of which sent former inmates back to jail — over the last decade.

Nationally, about 600,000 state prisoners return to the streets every year. While crime rates are falling, recidivism has changed little.

The new Pennsylvania study, which cost $98,400, followed one from 2015 that looked at what happened when inmates were paroled in communities across Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina and flooding devastated their New Orleans neighborhoods. Unlike the Pennsylvania study, which followed strict research protocols, experts referred to David Kirk's follow-up with the Louisiana inmates as a naturally occurring experiment.

Kirk wrote that his follow-up with post-Katrina parolees suggested they were less likely to re-offend when they were dispersed across the state rather than returned to neighborhoods with a concentration of former inmates.

“The conventional wisdom holds that it is better to send people home, but this suggests having a fresh start, a new beginning, an opportunity to forge new relationships in a new community may be beneficial, especially for older re-entrants and re-entrants with drug addiction and less social attachment,” Bucklin said.

Claire Shubik-Richards, executive director of the Pennsylvania Prison Society, hasn't studied the new report, but she has some questions about it.

“What I found interesting about it is that a lot of what we do here at the Society is trying to keep people on the inside connected to their networks on the outside,” she said. “There is a study that found there are certain types of family connections, particularly to a mother or child, that really made a difference in a person getting resettled in the community.”

While officials here aren't proposing routinely relocating parolees, Bucklin said they are weighing the study results as they seek options to reduce recidivism.

John Wetzel, Department of Corrections secretary, said the study could have far-reaching implications for helping parolees remain in the community.

“We release roughly 20,000 men and women back to the community every year, and this study demonstrates that there is no single answer to the best release plan for their future success,” Wetzel said.

Debra Erdley is a Tribune-Review staff writer. Reach her at 412-320-7996 or derdley@tribweb.com or via Twitter @deberdley_trib.