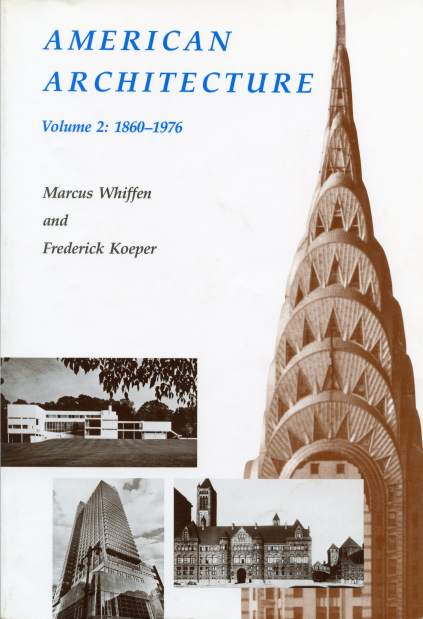

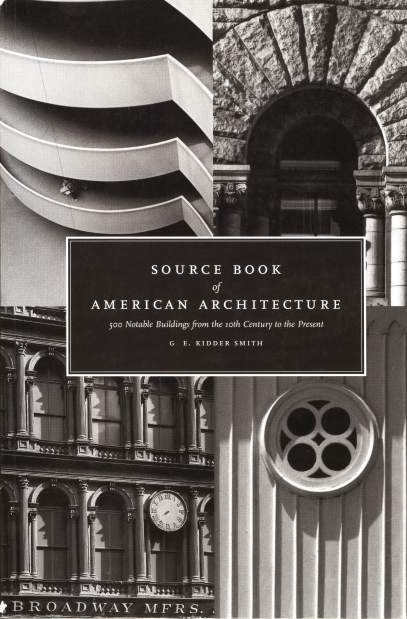

They are two of the most widely used histories of American architecture. They feature on their covers photo-collages of significant buildings:

One emphasizes New York's Chrysler Building, with smaller pictures of a big modern house on Long Island, a famous skyscraper in Philadelphia, and then our Allegheny County Courthouse and Jail.

The other shows the spiral interior of Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim Museum, a window of a country church in Missouri, a cast-iron storefront from the 1850s, and our Allegheny County Courthouse and Jail.

Do you get the sense from this that there must be something tremendously important in American architectural history about the Allegheny County Courthouse and Jail?

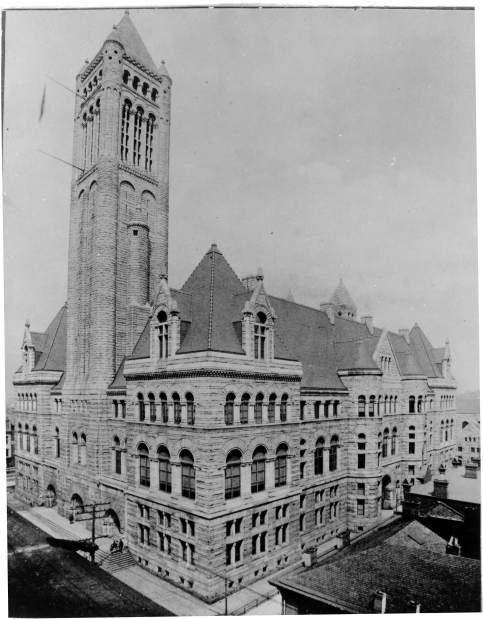

These two county buildings have long been considered by most historians to be among the most significant architectural landmarks in the nation.

Our 1888 courthouse, sometimes neglected and often dismally “modernized” by successive waves of uncaring or unaware county bureaucrats, is going to be 125 years old next week. And this building may in fact — at long last — get the honor it deserves in its own town.

The jury, so to speak, is still out on just how extensive and how well-done any rejuvenation of the courthouse may be, but County Executive Rich Fitzgerald has appointed several committees to consider just that. Preliminary plans are likely to be announced within the next few months.

The courthouse and jail were designed by the eminent Boston architect, H.H. Richardson. Historians view Richardson as part of a triumvirate of highly original American architects from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with Wright and Louis Sullivan, being the other two.

Richardson was by far the most honored — and imitated — architect of his day. But he died young, at age 47, as construction of Pittsburgh's courthouse was under way.

He said at the time, “If they honor me for the pigmy things I have already done, what will they say when they see Pittsburgh!”

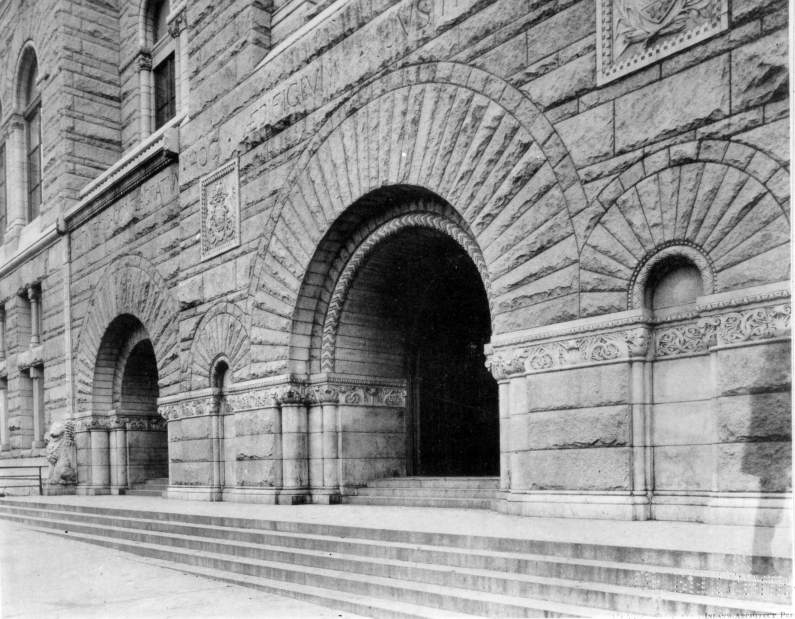

The courthouse today is full of contradictions. You can still find some of the grandeur and “majesty of the law” that Richardson envisioned. His magnificent four-story interior stair hall is intact, and the spaces that unfold around you as you climb his steps provide, perhaps, the finest architectural experience in the city.

In other ways, though, the building has become depressingly workaday and has suffered some sad indignities that compromise some of what Richardson envisioned.

The courthouse was set on what was called Grant's Hill, the highest land in the Golden Triangle. It was intended to overlook the city with a commanding presence. But Henry Clay Frick built a 20-story skyscraper directly across from it in 1902, blocking off the views both to and from the still-new courthouse.

And that was just the start.

Subsequently, city fathers decided to finally excavate “The Hump” — a steep rise in streets that made it difficult to access Grant's Hill. By 1912, Grant Street in front of the courthouse had been lowered an astonishing 15 feet in total. A plaza-like platform was built at the front to preserve the original entrances. But this didn't last long, as the platform was removed in the 1920s to enable the widening of Grant Street.

That necessitated a significant lowering of the entrances so that, sadly, when you enter this distinguished building today, you are doing so through its basement.

Compounding matters, space-starved city and county officials later wedged new offices into the interior — using the original high-ceiling space of the courtrooms, and permanently lowering courtroom ceilings.

Beyond that, virtually all the once-elegant interiors came, over the years, to be awash in ugly fluorescent lighting and drably painted hallways. Courtroom ceilings were lowered again as air conditioning was installed. Awkward and seemingly improvised entrance spaces for remodeled offices — and even for what is now County Council chambers — still abound. Convenience and ease of renovation has trumped any architectural awareness.

Those are among the bad things. At the same time, there's still a lot of good. Besides the grand stair hall — which you can experience after taking a latter-day stairway up from the basement entrance — the building has one fully restored, high-ceilinged courtroom that readily recalls the majesty Richardson had in mind. In the hallways, once-miscellaneous furniture has essentially been banned and replaced by deftly designed wooden benches, and strips of fluorescent lights have been replaced by period fixtures. The Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation and local historians have worked on these over the years.

A popular improvement has been the conversion of the courtyard of the courthouse — once a parking lot — into a parklet in the late 1970s. It's easy to enjoy this space and its central fountain, and be awed there by the number of windows that Richardson inserted into his heavy stone walls.

It's not clear to anyone yet how much restoration of the building will be possible and affordable. But a lot can be done even without major expenditures.

Aside from improving the individual courtrooms, some of which have a dated and worn modern style, attention can be paid to reception areas and entrances for individual offices. Beautiful period lighting fixtures should be retained, but possibly a sophisticated, modern supplemental lighting system — well hidden — can be devised to further illuminate halls and architectural details.

Finally, a program of “interpretation” should be undertaken, providing displays that illustrate and explain the differences between the historical monument that Richardson designed and the heavily used building of today.

Beyond that, can there be more restored courtrooms? Could somebody devise a better entrance? That all has to be determined. But it's good that a rethinking is under way.

John Conti is a former news reporter who has written extensively over the years about architecture, planning and historic-preservation issues.