George F. Will: Frederick Douglass championed American individualism

WASHINGTON

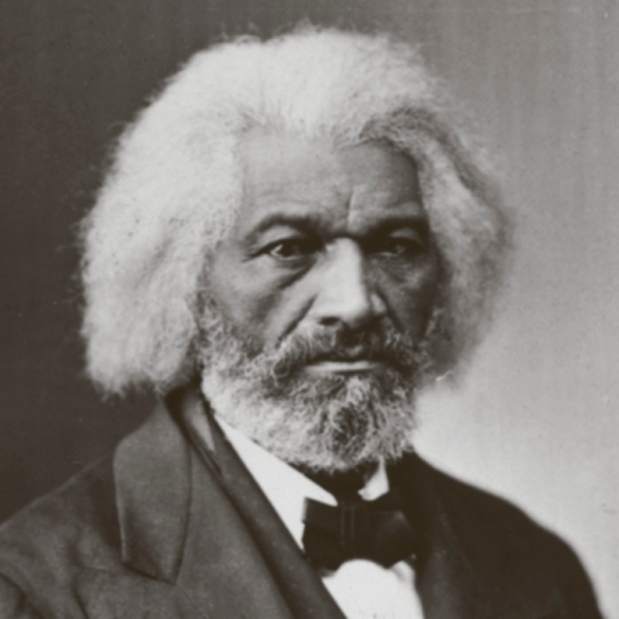

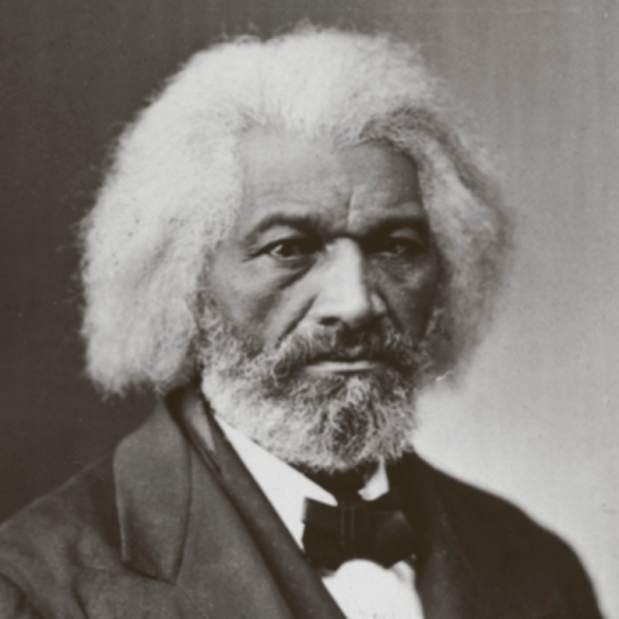

It was an assertion of hard-won personal sovereignty: Frederick Douglass never knew on what February day he was born on a Maryland plantation 200 years ago this month, because history-deprivation was inflicted to confirm slaves as non-persons. Later in life, Douglass picked the 14th as his birthday. This February, remember him, the first African-American to attain historic stature.

In an inspired choice, the libertarian Cato Institute commissioned a short Douglass biography by the Goldwater Institute's Timothy Sandefur, who says Douglass was, in a sense, born when he was 16. After six months of weekly whippings — arbitrary punishment used to stunt slaves' dangerous sense of personhood — he fought his tormentor. Sent to Baltimore, where he was put to work building ships — some of them slave transports — he soon fled north to freedom, and to fame as an anti-slavery orator and author. His 1845 “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass” is, as Sandefur says, a classic of American autobiography.

Abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison said there should be “no union with slaveholders.” They said what the Supreme Court would say in its execrable 1857 Dred Scott decision — that the Constitution was a pro-slavery document. Douglass, however, knew that Abraham Lincoln knew better. “Here comes my friend Douglass,” exclaimed Lincoln at the March 4, 1865, reception after his second inauguration. After Appomattox, Douglass said: “Slavery is not abolished until the black man has the ballot.” If so, slavery ended not with the 13th Amendment of 1865 but with the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Douglass opposed radical Republicans' proposals to confiscate plantations and distribute the land to former slaves. His individualism, says Sandefur, was based on self-reliance. Although Douglass entered the post-Civil War era asking only that blacks at last be left to fend for themselves, he knew that “it is not fair play to start the Negro out in life, from nothing and with nothing.” A 20th-century Southerner, President Lyndon Johnson, agreed.

By the time of Douglass' 1895 death, sinister sentimentality about the nobility of the South's Lost Cause saturated the nation: The war had really been about constitutional niceties — “states' rights” — not slavery. This, Sandefur says, was ludicrous: Before the war, Southerners “had sought more federal power, not less, in the form of nationwide enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act and federal subsidies for slavery's expansion.”

Nevertheless, Confederate monuments were erected in the South. As an academic, Woodrow Wilson paid “loving tribute to the virtues of the leaders of the secession, to the purity of their purposes.” As president, he relished making “The Birth of a Nation,” a celebration of the KKK, the first movie shown in the White House.

Douglass died 30 years before 25,000 hooded Klansmen marched down Pennsylvania Avenue. That same year, Thurgood Marshall graduated from Baltimore's Frederick Douglass High School, en route to winning Brown v. Board of Education . Douglass, not Wilson, won the American future.

George F. Will is a columnist for Newsweek and The Washington Post.