High-tech vision: Nonsurgical device allows blind to gauge surroundings

Bennett Lehman is blind, but he's learning how to, in a sense, turn his tongue into an eye.

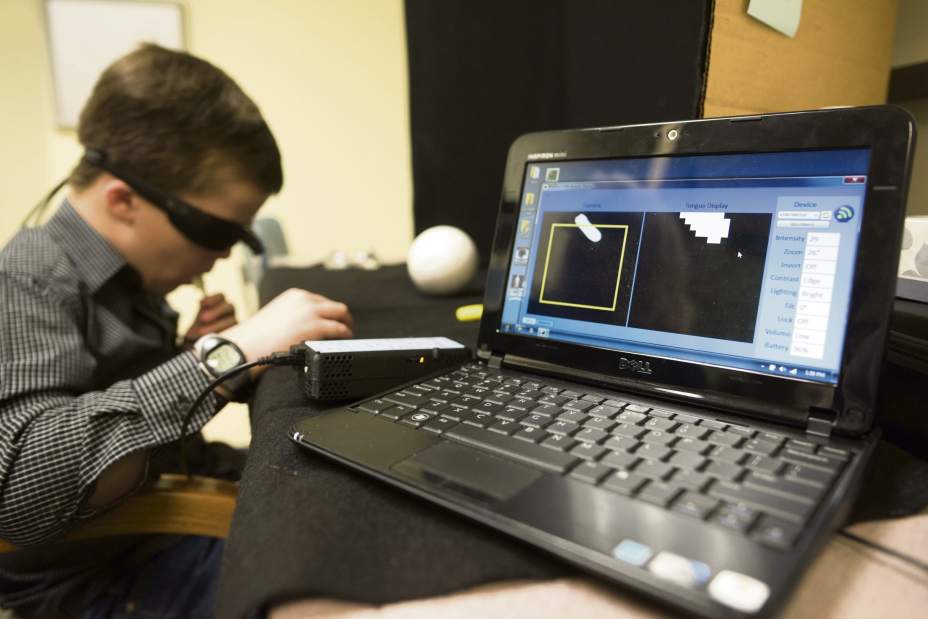

Last week, with his parents and doctors looking on, the 8-year-old boy located, then grabbed, a yellow highlighter pen placed in front of them. He did the same with a ball.

Lehman achieved this by running his tongue across a device containing hundreds of electrodes. He wore a pair of sunglasses containing a video camera connected to the device.

"There's some tingling and hotness on my tongue," he said, describing the sensation.

Bennett is part of a study involving children using a non-surgical visual prosthetic called the BrainPort V100. Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC is conducting the study with the gadget created by Wisconsin-based Wicab Inc. So far, eight children have enrolled.

"I think this may change people's lives because it can help them see and stuff," Bennett said. "Probably, it could change my life. It's amazing that they can come up with this type of technology."

The BrainPort is a vision aid that enables the blind and severely visually disabled to gauge their immediate surroundings and determine the way the brain interprets information. The battery-powered device has a tiny video camera that is mounted on a pair of sunglasses and a minuscule lollipop-type mouthpiece containing 400 electrodes.

The camera is designed to collect images, alter them into electrical signals and send those signals to the lollipop gadget. The lollipop, in turn, sends sensory information to the brain. Users describe the feeling as pictures being painted on the tongue with tiny, tingling bubbles — Braille for the mouth.

Bennett wore camera-equipped sunglasses inside UPMC Eye & Ear Institute as Jacqueline Fisher, the study's clinical research coordinator, placed items in front of a black felt screen. She placed each shape in front of him, asking, "Are you feeling something now? What do you think it might be?" After a few seconds, Bennett accurately answered. "Is it the pen?"

"Good job," Fisher said. "Fantastic."

He also used it to read the short word, "cat."

"Pretty amazing," said Dr. Ellen Mitchell, a UPMC pediatric ophthalmologist and assistant professor of ophthalmology at University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. "It doesn't give them vision; they don't actually see, but what it does is it gives a visual representation of what they are seeing on their tongue. With training, people like Bennett can actually decipher what they are seeing."

BrainPort has been available across Europe since 2013, and the Food and Drug Administration in 2015 approved it for use in the United States. The device costs around $10,000 and has been studied extensively in adults.

Bennett traveled to Pittsburgh with his parents and older brother from Jefferson, Wis., to participate in the study last week. Within two hours, he began picking up skills with the BrainPort's assistance.

"Part of the training is they are able to feel the objects, like the pen or sphere, before we actually have them scanned, and decipher what they are," Mitchell said. "On his tongue, he would feel something in the shape of a circle to help him identify that."

The device exhibits how brains of the blind can be retrained to recognize objects. There's still a cord that connects the camera glasses to the lollipop, but a wireless device is in the works, and Mitchell hopes to add those to the UPMC study.

Bennett's sight deteriorated after birth. He has a rare genetic eye disorder called Axenfeld-Reger syndrome and glaucoma and lost complete sight, besides light perception, at age 4.

He heard about the BrainPort studies for children at school and convinced his mother to pursue a trip to Pittsburgh.

"He was really excited and kept saying, 'Mom, let's try it,' " said his mother, Amy Lehman, who is a teacher for visually impaired students. "Bennett researched everything he could find. The one thing he said he'd like to do by himself is use the bathroom. Right now with having no vision, just the light perception, one of us has to walk him into the bathroom and say, 'The toilet's on the left, the sink's on the right.' Just for him to have some independence with this would be great for him."

Bennett concurred.

"In my classroom at school, when they move desks around, I have no clue where anything is," he said. "Just to not have a friend or teacher show me everything would be great."