McCandless woman 1st in region with implant aimed at halting seizures

Each night before bed, Georgette Nichols brushes her teeth, washes her face and holds an electronic wand to her head to download brain wave activity from a computer chip embedded in her skull.

“No big deal,” Nichols, 46, of McCandless said with a laugh. “We all have our daily routines. This is now part of mine.”

For 34 years, Nichols endured unpredictable epileptic seizures that sometimes made her feel like an outcast.

“I'd be at work, and I'd just go into a trance and start staring,” said Nichols, a sales representative at JC Penney in Ross Park Mall. “When I'd come out of it, I always had a feeling of frustration. To be honest, I felt like a freak.”

The tiny device, which was surgically placed in Nichols' skull, is giving her newfound hope by sharply reducing the frequency and duration of her seizures. Known as the RNS Neurostimulator, or RNS system, the brain monitor sends bursts of electrical stimulation to halt oncoming seizures.

Nichols in January became the first patient in Pittsburgh to receive an RNS device in UPMC Presbyterian in Oakland. Since then, three more local patients have received the $50,000 treatment, which is offered in 81 medical centers across the country. Nationally, about 500 people have received implants, including those involved in clinical trials.

“This is the first time in the history of neurosurgery that we have a real brain-computer interface that can respond to a patient's brain activity,” said Dr. Mark Richardson, director of epilepsy and movement disorders surgery at UPMC. “It offers a lot of potential for us to learn more about epilepsy networks within the brain.”

About 3 million Americans have epilepsy, a chronic brain disorder that causes uncontrollable seizures, loss of consciousness, shaking and staring.

In most cases, direct causes of epilepsy are unknown.

Frank Fischer, CEO of the RNS device maker NeuroPace Inc., based in Mountain View, Calif., estimates that more than 500,000 Americans with epilepsy could be helped by the innovative treatment.

“The most impressive thing we've heard comes from patients or their family members thanking us for giving them their lives back,” Fischer said. “They're getting the opportunity to live the quality of life that they're entitled to.”

About 70 percent of implant recipients report at least 50 percent fewer seizures within six years, he said. However, an implantation does not necessarily mean patients can immediately discontinue their medicine. Nichols, for example, still takes three forms of anti-seizure medication.

17 years in development

The RNS system, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2013, was in development for 17 years.

Here's how it works: The battery-powered, programmable neurostimulator is implanted in a patient's skull, and leads or wires connected to electrodes are implanted in the brain area from which seizures originate. The technology is designed to short-circuit seizures by detecting abnormal brain-wave activity and delivering brief bursts of electrical stimulation through the electrodes to halt a seizure or shorten its duration.

Before FDA approval, clinical trials of the device showed a 38 percent reduction in seizure activity within several months for patients, according to Dr. Nathan Fountain, chairman of the advisory board of the Epilepsy Foundation in Landover, Md.

“The epilepsy community is excited about this because it's great technology. We're hoping we can use this to discover new things about epilepsy,” he said.

At the same time, doctors emphasize that they promote the approach not to cure seizures but to reduce them when medication is ineffective. The only certain epilepsy cure is targeted surgery to remove parts of the brain where seizures begin — an option unavailable to many patients, Fountain said.

The RNS option is not cheap, but it's generally covered by insurance companies. The device, along with equipment needed to download data, costs about $37,000, before surgery and diagnostic testing.

“It is expensive,” Fountain said, “but it's worthwhile if you're a patient who experiences a reduction in seizures.”

Proactive patients

Patients who receive the RNS device need to take an active role for true success. Besides wearing the device, they must upload data captured by the electronic wand to a server accessible by the doctor and NeuroPace engineers.

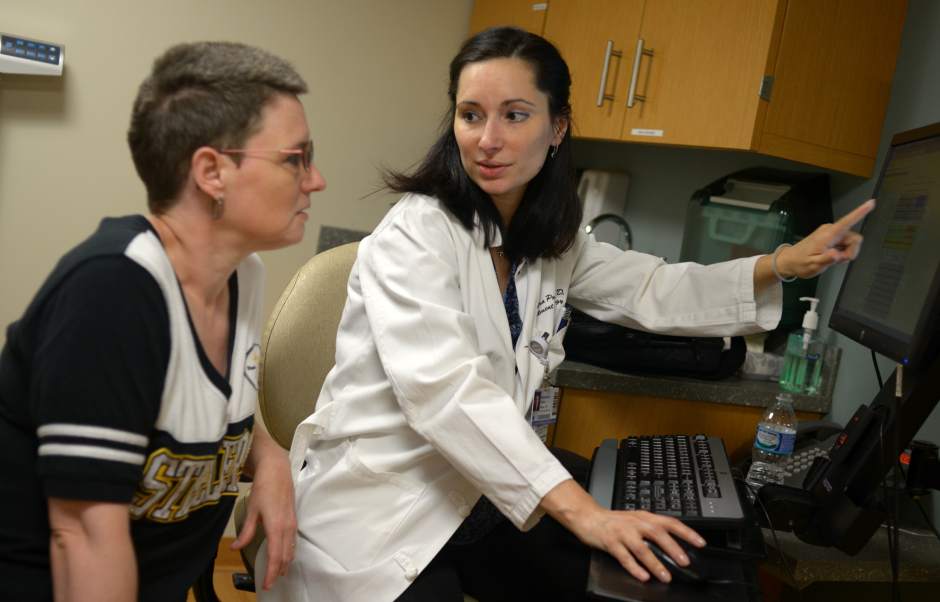

Patients transfer the data to a laptop and send it each week to doctors for detailed analysis. By doing so, “we can teach this little device how to properly detect the seizure signature,” said Dr. Alexandra Popescu, medical director of UPMC's epilepsy surgery program.

The data help doctors continually reset the RNS device to better combat seizures. In some patients, the process can take as long as two years for optimal benefits, Richardson said.

“Every person's seizure activity is very different,” he said. “But it's really exciting that we now have the opportunity to basically reprogram the device in ongoing fashion.”

Fischer estimated that just 10 percent of implant patients have not improved with the technology. Some patients, like Nichols, noticed significant improvements almost immediately.

“I averaged three to four seizures a week for most of my life,” she said. “Now I can go a week without any incidents. And the ones I have are shorter; less than 30 seconds. My husband noticed right away. I have a lot more confidence.”

Nichols' advice to other epileptics is to be proactive and never give up.

“Don't close your mind off to any kind of treatment,” she said. “A couple years ago, I had never heard of this, but I was always asking questions and doing research.

“Now I feel like I've got a brand new life.”

Ben Schmitt is a Trib Total Media staff writer. Reach him at 412-320-7991 or bschmitt@tribweb.com.