Kaufmann's murals have a tale to tell

Curator Blake Milteer leads you to an unmarked, locked metal door at the side of a gallery at the Fine Arts Center in Colorado Spings, Colo., and opens it to a bare concrete stairway.

You follow him down into a windowless, climate-controlled basement, turn left, take 10 steps, and there they are, bubble-wrapped in storage in front of you: 10 pieces of art that played an important part in Pittsburgh's history.

These huge 8-foot-by-15-foot paintings go back exactly 75 years — to a time when most women wouldn't dare go shopping Downtown without wearing a hat and gloves, and men were almost always in suits and ties.

They come from a time when Kaufmann's Department Store (now Macy's) was run by Edgar J. Kaufmann, a patron of art and architecture, a key figure in the first Pittsburgh “Renaissance,” and one of the most astute merchandisers of his time. He commissioned these paintings by muralist Boardman Robinson in 1929 and, for almost 25 years, they graced the high-ceilinged first floor of Kaufmann's Downtown store.

Why they are out here in Colorado Springs, though, is only part of a story.

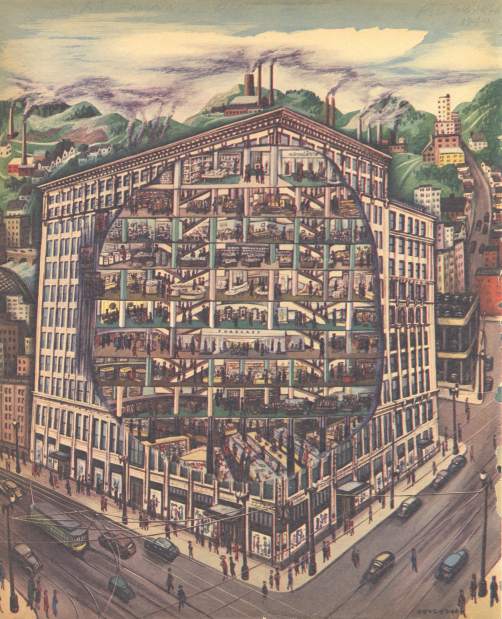

Kaufmann's in the 1930s and '40s was not just a department store, but something of a cultural center and art and design exhibition venue at the same time. In 1944, Fortune magazine did a full-blown article on Kaufmann, his merchandising ideas and his use of art in his store, illustrating it with a large cutout drawing of the 12-story emporium.

It's worth remembering Kaufmann and his contributions to the city now, 59 years after he died, at a time when Macy's is reported to be considering reducing the Downtown store to just its first four floors and the artistic interiors that Kaufmann shaped have long since been updated.

Based on articles in the local papers at the time, it was a major social event when the murals were unveiled in April 1930 in the newly renovated Kaufmann's first floor. The program included the mayor, the U.S. secretary of labor, who spoke on “Art and Labor,” and Kaufmann himself, who set forth his ideas on “Art and the Merchant.”

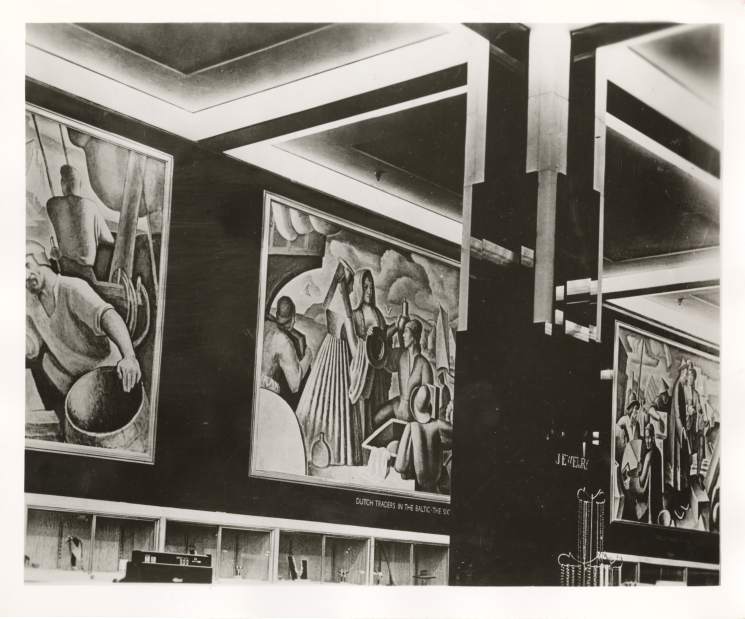

The dramatic and elegant first-floor renovation was produced in the then-modern art deco style by the accomplished local architect Benno Janssen, a favorite of Kaufmann's. It reflected ideas supplied by Joseph Urban, the most famous art deco designer of the time. The redecorated space featured columns encased in shiny black Carrara glass produced by Pittsburgh Plate Glass and an unusual indirect-lighting scheme provided by Westinghouse.

The display cases and counters were crafted of blond mahogany, and, in a Kaufmann innovation, set diagonally across the first floor.

“This new layout is the most radical that has been made in the retail field,” enthused one dry-goods trade journal.

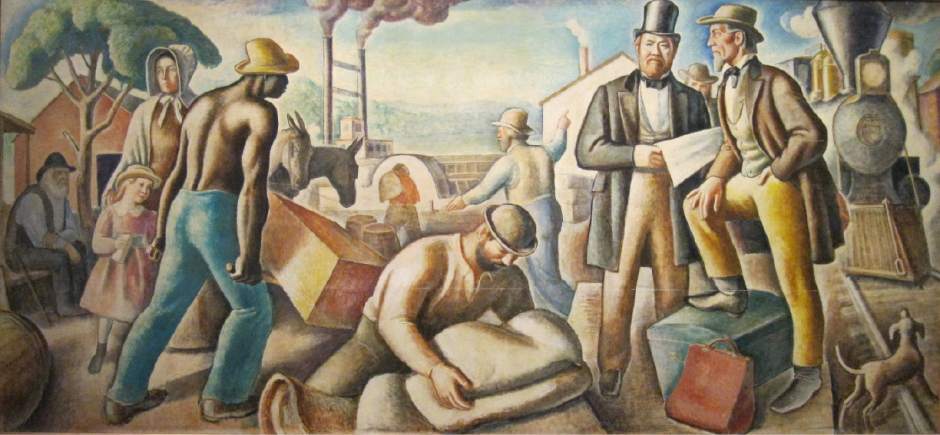

High above the floor were the Robinson murals, a cycle of 10 related paintings portraying the “History of Commerce.” The scenes narrated a story that started with trade among the Persians and Arabs and ended with “Trade and Commerce in the 20th Century” — muscular workers constructing a building with a city a little like Pittsburgh in the background.

The murals have historical importance on their own merits. Robinson was a friend and mentor to Thomas Hart Benton, the Depression-era muralist who, ultimately, surpassed Robinson in fame. Robinson and Benton innovated a style in which they used the abstract forms of Cubism to fashion their blocky figures, but nevertheless rendered them realistically. This style influenced the hundreds of murals subsequently painted during the Depression in post offices, municipal buildings and courthouses across the country.

The Kaufmann's murals were impressive enough to have been reproduced on arty postcards of the time and were widely published in art journals. Even Time mentioned them. In 1930, Robinson won the gold medal of the Architectural League of New York for what he did in Pittsburgh.

The murals came to Colorado Springs essentially because Robinson did. Robinson had abandoned the artistic hot house of New York City to teach at art schools in the Rockies. He helped found the Colorado Springs Arts Center and is a revered figure in art circles in this town. He died in 1952.

The murals, removed from Kaufmann's in a 1950s renovation, came into the care of Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, which sought to find a Pittsburgh museum to take them. But the huge murals are hard to display because of their size, and no one wanted them. History & Landmarks did put three of them up in the Sheraton at Station Square, but later had to move them for a renovation there.

The Arts Center in Colorado Springs subsequently purchased them in two batches in 1993 and 1996, as experts at the Carnegie Museum and at History & Landmarks decided this institution would be the best home for them. It exhibited them in 1996-97 and again in 2011 — devoting a 6,000-square-foot gallery to them.

The murals were loaned for a time to the adjacent Colorado College for display. They are in storage, and there's no plan to mount them as a show again anytime soon, though one or another of the panels may be brought out for display from time to time.

John Conti is a former news reporter who has written extensively over the years about architecture, planning and historic-preservation issues.