Late Pittsburgh photojournalist's talent, legacy revealed to daughters

Lynn Rice stares at the framed black-and-white photo.

It is late in the day, and the room grows dark. At her feet is a box of family relics. In a corner is a grandfather clock, its ticking the only noise in the room.

“Look at those eyes,” she says in a near-whisper, cradling the image of her late father. “The eyes tell the story. But what story he's trying to tell, I don't know ...”

In life as in death, Ed Salamony kept his stories to himself.

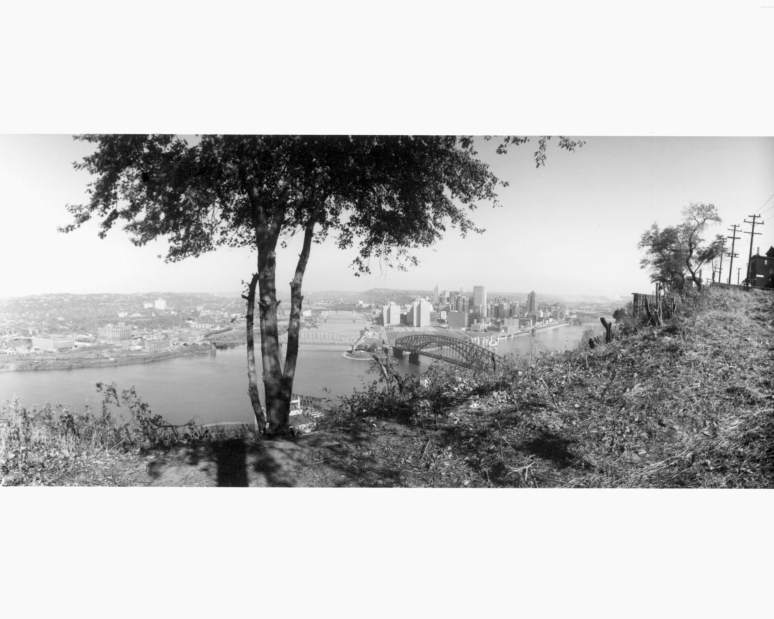

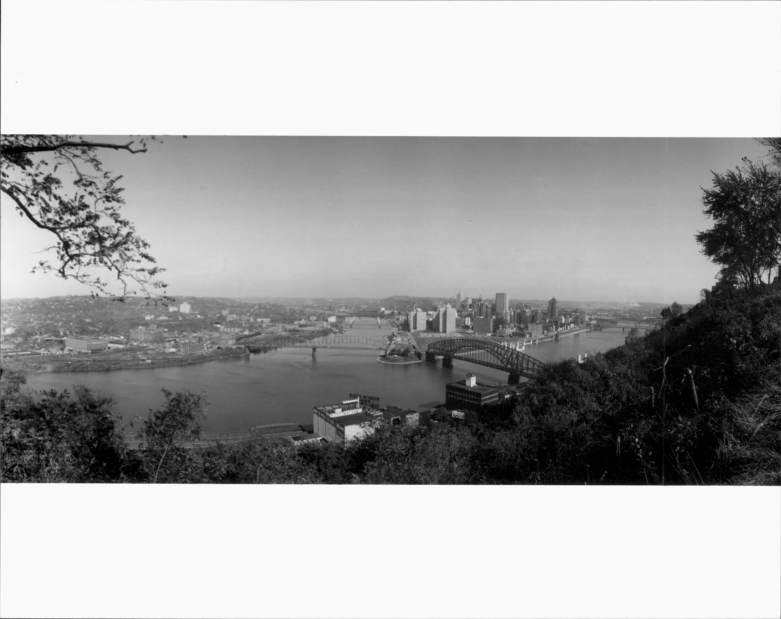

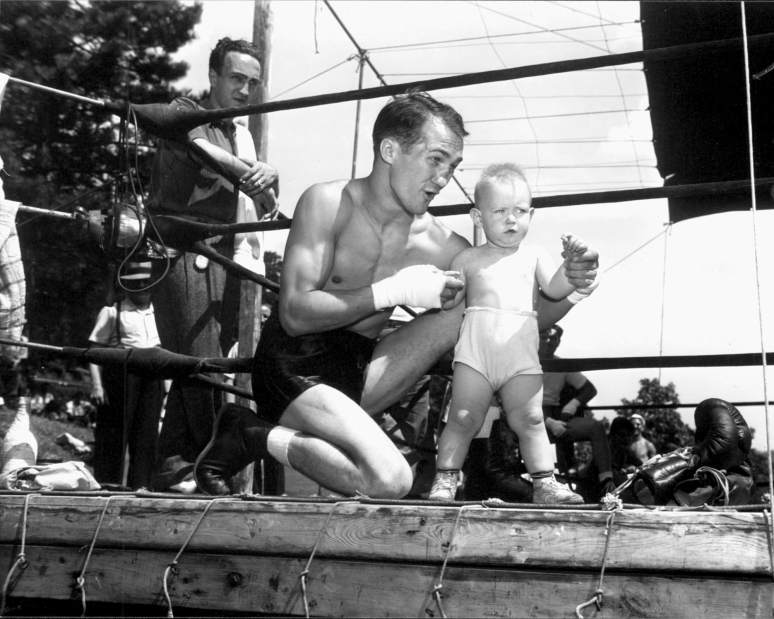

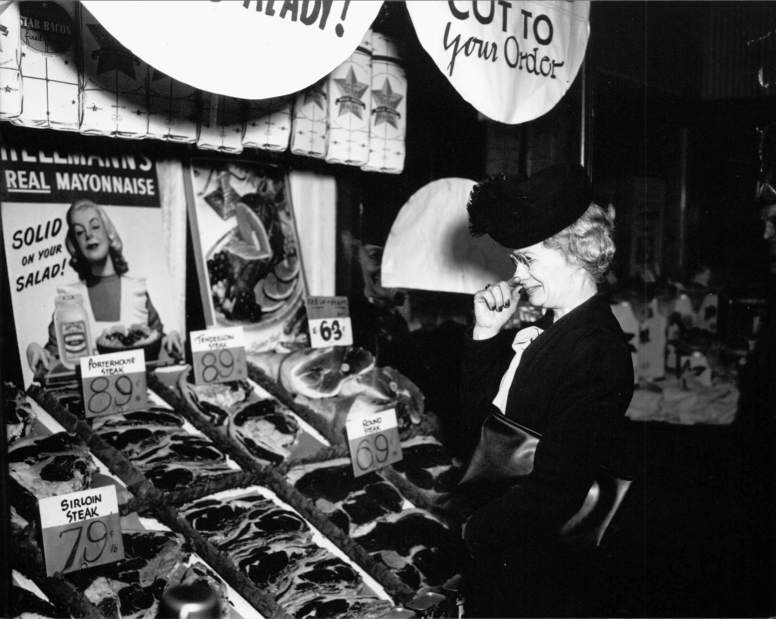

An accomplished photojournalist, Salamony worked for the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, starting in 1934. He was a war correspondent in Italy during World War II, and in 1953 became president of the Pittsburgh Press Photographers Association. He covered the Great Depression, presidential visits, Roberto Clemente and the day-to-day tragedy and triumph of a Pittsburgh that no longer exists.

He saw more than most.

But when he went home to his family, he never spoke of it.

Not a word.

“He kept it separate,” said Rice, 76, of Pleasant Hills. “I'm not sure my mother even knew.”

Salamony died in 1999, 15 years after his wife. He sat down for dinner one night and passed peacefully in his chair. A neighbor found him in the morning. He was 89.

In his final days, Salamony dug up his old glass negatives, apparently with the idea of developing them to share — finally — with his daughters.

He sought help at Bernie's Photo Center in the North Side, where he met Frank Watters, director of the Photo Antiquities museum next door. The men became friends. Watters visited Salamony at his South Hills home, and they smoked cigars on the porch and talked about photography.

In time, Watters agreed to get the negatives developed — three sets, one each for Salamony's daughters and one for the museum.

It's not clear what became of the daughters' prints. They never received them.

But the third set has sat virtually untouched in a box in Watters' office. Aside from 20 images of a Shantytown that arose in the Strip District during the Depression, which Watters displayed in an exhibit in 2002 and again this year, almost no one has ever seen the prints.

Which is a shame, Watters said. Because they are spectacular.

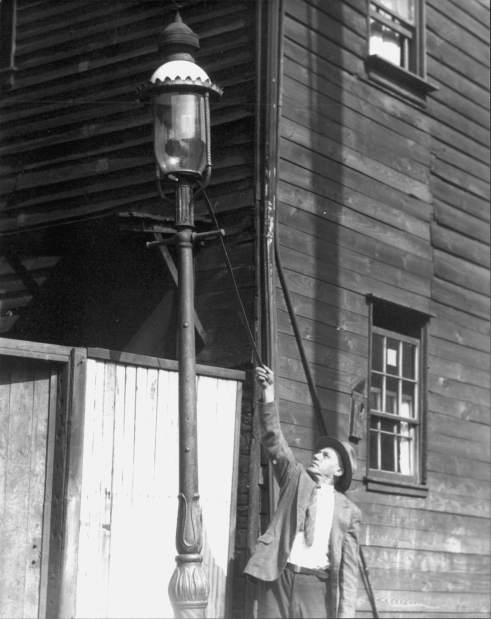

Salamony's artistry was in his ability to capture everyday scenes and give them deeper meaning, said Watters, who intends to reveal them to the world in an exhibit in the fall.

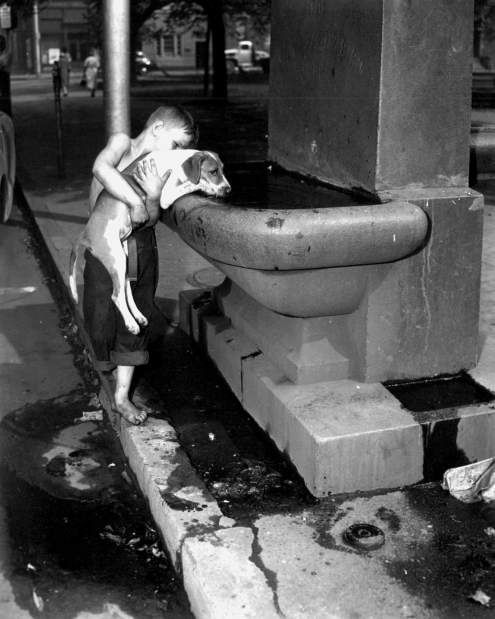

One photo is of women tossing ration booklets from windows at the end of World War II. The next shows violinists playing over a casket. Another captures a poor boy — shoeless, shirtless and covered in grime — holding a dog up to drink from a public fountain.

“Ed was a master at capturing a single moment in time,” Watters said. “I mean, look at that photo —its humanity. The kid is obviously a poor street urchin, yet he takes the time out to give the dog a drink on a hot day. It's my favorite photo of his.”

Salamony's second daughter, Mary Jo Gaitens, 68, of Mt. Lebanon, recently viewed some of the prints for the first time. She paused on one that shows firefighters battling a blaze on the Downtown side of the Monongahela River.

“Oh my God,” Gaitens said, staring in astonishment at the photo. “He would have seen this, come home, and ... said nothing.”

Rice, Gaitens and their brother Gene, who died in 2013, certainly knew what their father did for a living.

But they had no idea how talented he was.

And they cannot explain why he kept it a secret.

As a child, Gaitens regularly followed her father into his basement darkroom to watch him develop photos — mostly close-ups of people she did not know. But any information gleaned from the subjects came through observation, not explanation.

“I watched him go through all the processes, dipping it in all this dark water,” Gaitens recalled. “But he never told me what they were for.”

In truth, the girls will never understand their father's silence.

But they don't entirely care.

Ed Salamony was everything they ever wanted: a wonderful father, a kind man who never yelled or got angry, who was always there for them, even if he chose not to share the things he witnessed.

“I'm proud of him, of course I am,” Rice said. “But I don't care about that other part. I'm more ... I'm just his little baby girl. And that's it.”

She returns her focus to the framed photo. It shows her father, staring straight ahead and holding his old camera.

“The eyes tell the story. But what story he's trying to tell, I don't know,” she says in a near-whisper. “But his eyes are saying something.”

The clock in the corner continues to tick.

“They're talking to me,” Rice says.

“No? I see it.”

Chris Togneri is a Tribune-Review staff writer.