Modest Lawrenceville library holds a place in history

It is sometimes the least imposing of our old buildings that have the best stories to tell.

The 118-year-old Lawence-ville branch of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, while it has a beautiful Beaux Arts-inspired facade of Roman brick and white terra cotta, doesn't have the massive grandeur of some of Pittsburgh's other libraries.

It sits along Fisk Street, one of the sloping residential streets of modest, closely built, Victorian-era brick homes that lead down from Penn Avenue to Butler Street. The library is relatively small, but after you go in, you feel you are in one big, high-ceilinged space with a curved, apse-like back wall at the rear. Huge 10-foot- to 12-foot-high windows light the room from all sides.

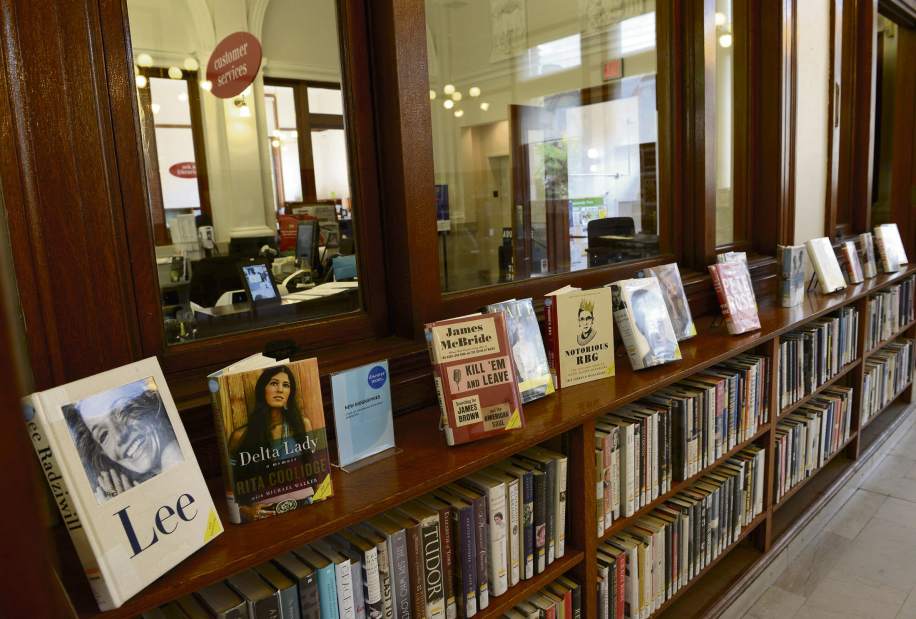

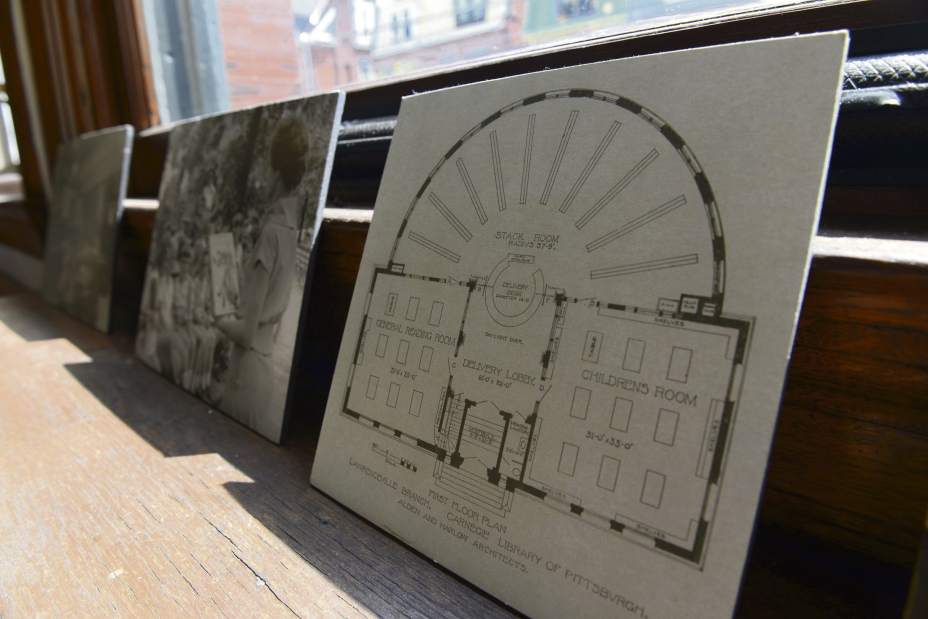

The first time you visit, the floor plan is instantly readable: very simple and very basic, as would befit a Beaux Arts plan. There is a children's area on your right — it's enclosed by oak-framed glass walls that rise from about waist-high to about two-thirds the height of the room — and an adult reading area to your left, similarly enclosed in glass and wood.

The main desk is a few more paces in front of you, and behind it the library's book stacks radiate from the desk — like the spokes of a wheel — to the curved rear wall of the building.

The simplicity of the building, and the ease with which you discern its functions, make it an especially gratifying architectural experience.

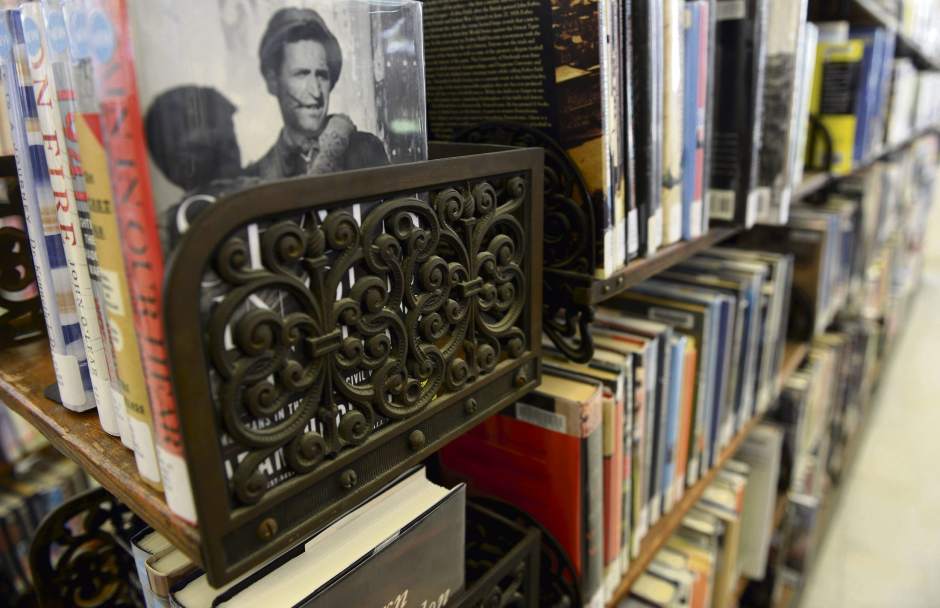

But there's more to it than that: This library is mostly intact from when it was built. When you look closely at the adjustable shelving in the radial stacks, for example, you realize that they are the original metal and pine shelves, with original decorative cast-iron fixtures at the end caps.

Though some changes have been made — computers, of course, have replaced card catalogs, and the librarian's desk area has been remodeled — it is nevertheless a building that functions today in just about the same way it did when the library opened in 1898. That's a rarity.

Then, when you dig just a little deeper, you learn even more. That children's area is believed to have been just the second specially designed and furnished children's room in any public library in the United States — an important feature now in use everywhere today. And radiating stacks? Most historians seem to feel that was the first use of those in the United States, too. The glass walls? They were designed for economy of management, which must have appealed greatly to Andrew Carnegie himself. They allowed one librarian, sitting at the central desk, to observe all the activities anywhere in the library.

Moreover, this was the first neighborhood branch of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh and it set a precedent in basic design and style for small Carnegie libraries built, not just in Pittsburgh, but all over the country in the first years of the 20th century. Its architects were Alden & Harlow, the designers of the big central Carnegie Library complex in Oakland, who quickly thereafter became a favorite of Andrew Carnegie and the staff members who administered his library endowments. (Carnegie endowed some 3,000 libraries throughout the United States, Canada and Britain.) Those staff members published the Lawrenceville design and sent it out to library building committees across the country — giving it an influence far beyond Fisk Street and Lawrenceville.

Alden and Harlow were probably the most prominent architects in Pittsburgh in the late years of the 19th century and the very first years of the 20th. Those were the years, you might remember, when Pittsburgh was incredibly rich and its banks held more money than those in any city other than New York. Frank Alden and Alfred Harlow not only designed the Carnegie Library and Museum in Oakland, but several of the best Downtown office buildings of the day and many of the finest mansions and other large houses for the “captains of industry” in the East End and in places such as Sewickley and Edgeworth, where the two architects also made their own homes.

Their firm was essentially the successor firm in Pittsburgh to H.H. Richardson, the designer of the Allegheny County Courthouse and Jail in the late 19th century. Alden had come to Pittsburgh to supervise Richardson's work here.

The firm designed no fewer than eight neighborhood library branches in Pittsburgh, most of which looked somewhat alike, as well as the Carnegie libraries, big and small, in places like Homestead and Oakmont. You can even track a Carnegie Library — designed by Alden & Harlow in the same basic style as what we have here — all the way to Michigan.

But whether designed by Alden & Harlow or by other architectural firms across the country, there are hundreds of libraries that can trace the elements of their design directly to the Lawrenceville library here.

John Conti is a former news reporter who has written extensively over the years about architecture, planning and historic-preservation issues.