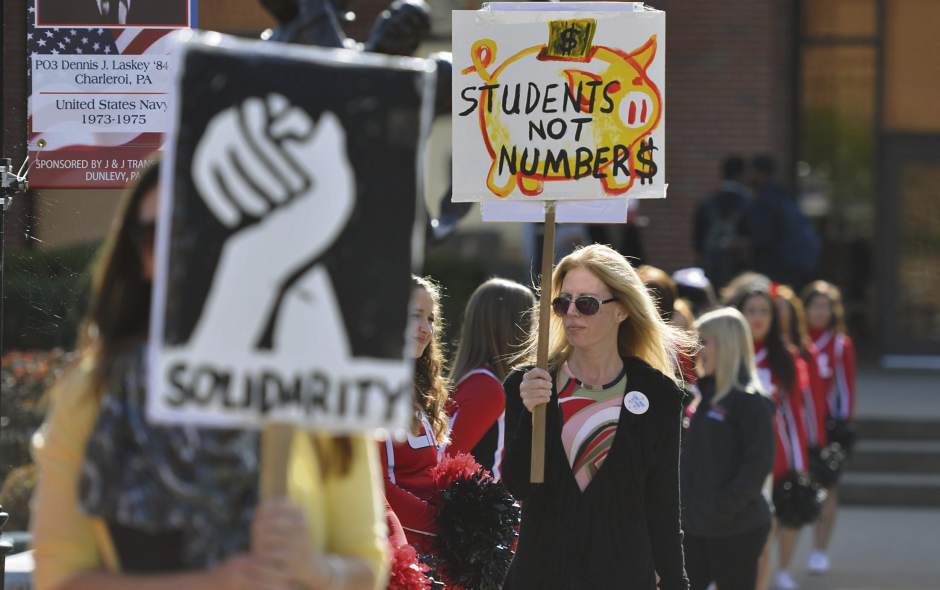

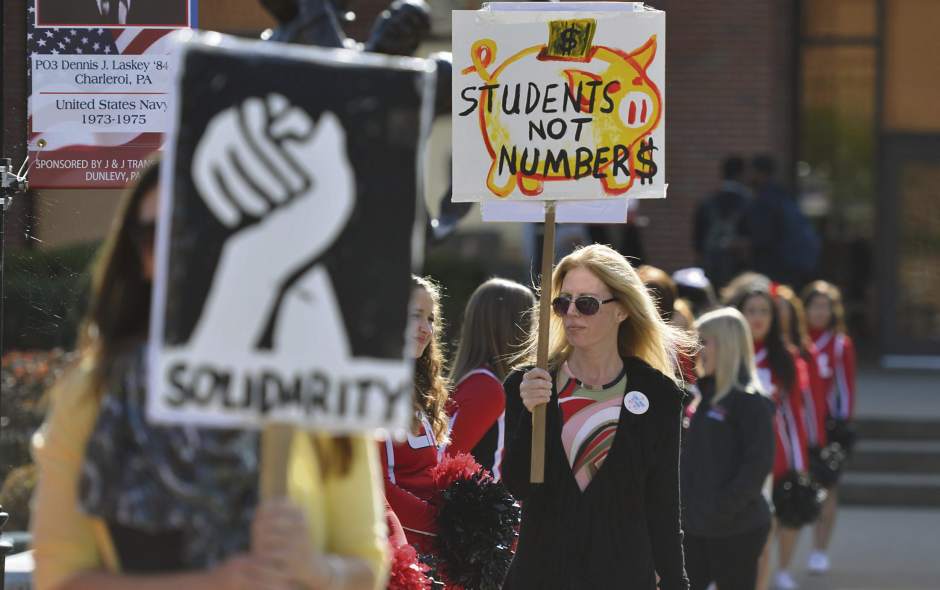

Labor dispute puts university students in middle

Chad Dobbins was worried.

An email from a professor in his MBA program at Clarion University of Pennsylvania had an ominous ring to the 38-year-old Brookline father of two.

The message warned that university faculty could strike beginning Wednesday if state and union negotiators failed to reach a new contract agreement. The two sides resumed a three-day bargaining session Friday.

“If there's a strike, and they stay out, I won't get my funding,” Dobbins said of the loan financing his online studies while he works as a construction project manager.

His loan terms require that he take at least six credits each semester.

A condensed, seven-week course worth 1.5 credits — which would bring him to that threshold — is scheduled to begin Oct. 24.

“I'm sweating it a little,” Dobbins said from a work site in Texas.

About 5,500 faculty members and coaches at Pennsylvania's 14 state-owned universities have worked without a contract since June 30, 2015.

Both sides announced Saturday that they had reached agreement on at least one point: No one would comment on the ongoing negotiations, expected to last through Sunday, “to help minimize distractions,” according to a joint statement.

Experts say the increasingly tense labor dispute threatening to disrupt classes for Dobbins and more than 104,000 other students at state-system schools — including California, Clarion, Edinboro, Indiana and Slippery Rock universities in Western Pennsylvania — is just the most-recent symptom of changes that began rolling across campuses nationwide several decades ago.

Shifts in underwriting the costs of college triggered the change, said William A. Herbert, executive director of the National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions.

State support in 1983 covered 63 percent of costs for Pennsylvania's state-system universities. Such support accounted for about 25 percent this year.

“The continuing decline in public support for higher education since the Reagan era has placed financial pressures on all concerned: faculty, college administrators, students and parents,” Herbert said. “Among the consequences of the decline in public funding are more difficult campus-based collective bargaining and the nationwide student-debt crisis.”

Herbert cited the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, City College of San Francisco, and the University of Illinois at Chicago as schools that endured faculty strikes in the past two years.

Protracted contract negotiations in the Pennsylvania state system are not new. Although professors have never walked off the job, talks have grown increasingly tense this year with administration proposals calling for greater control over teaching assignments, increased caps for the use of adjuncts and greater use of online education.

Such concessions are needed to give universities the flexibility needed to thrive in the 21st century, said Frank Brogan, chancellor of Pennsylvania's State System of Higher Education. He said 30-year-old contract language needs to give way to modern management needs.

Howard Bunsis, an accounting professor at Eastern Michigan University who chairs the American Association of University Professors Collective Bargaining Congress, said he has heard such claims from universities across the nation.

“The administrators use words like flexibility and nimbleness. Those are just code words that they don't want to pay people for the important work of teaching our students,” Bunsis said. “They want to pay them as little as possible and give them as little say as possible.”

Bunsis called it the “corporatization” of higher education.

Protected by longstanding contract language that limits the use of adjunct faculty to 25 percent of the teaching load, Pennsylvania's state-system universities have escaped much of the impact of the trend. Nationwide, adjuncts have grown from 43 to 70 percent of college and university faculty since 1975, according to the Department of Education,

At private colleges and universities across the region, the use of adjuncts varies dramatically — ranging from 48 percent at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh to 22 percent at St. Vincent College in Latrobe.

State-system officials want to increase the cap on adjuncts to 30 percent. Many of its schools have yet to hit the current 25 percent cap.

A few schools, however, need more adjuncts to accommodate special programs such as music education, state-system spokesman Kenn Marshall said.

Kenneth Mash, president of the Association of Pennsylvania State College and University Faculties, worries state-system proposals could reduce the number of tenure-track positions, stretch science professors thin and reduce pay for some adjuncts, who would have to teach five classes per semester to be considered full time rather than four as currently required.

“If they aren't offered a fifth class, that's a pay cut for our lowest-paid teachers,” Mash said.

The union leader also worries that students who are paying more than ever could suffer from proposals that would expand online education and class sizes.

“If you come to one of our institutions, you come because they are teaching institutions,” Mash said. “So many of our students are first-generation college students, and it takes nurturing for them to succeed.”

Back in Texas, Dobbins said he was oblivious to the debate until he opened that email from his professor.

After taking on loans and juggling work and family commitments, all he wants to do is finish this semester on time.

Debra Erdley is a Tribune-Review staff writer.