Pitt study explores people with HIV leading healthy lives into older age

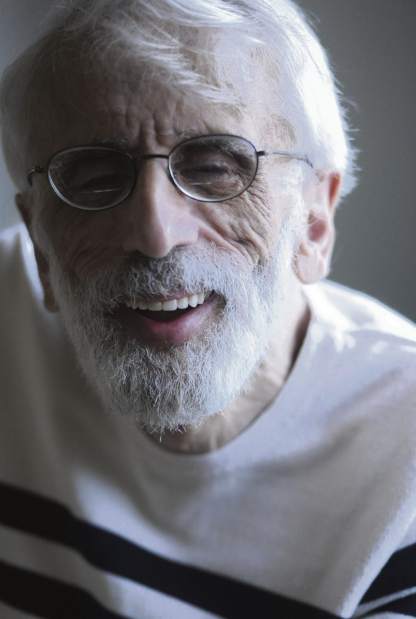

Treatments for HIV have evolved through several generations since August “Buzz” Pusateri tested positive for the virus 30 years ago.

The latest drugs promise a near-normal life span with few side effects for people newly diagnosed.

But side effects of earlier drugs, and damage the drugs couldn't prevent, linger in Pusateri's 77-year-old body.

In addition to two pills for HIV, he takes medicine to relieve numbness in his feet likely caused by early treatments. He wears a beard to cover facial scarring that new patients won't get, and some of his body's fat has migrated to his midsection, creating a condition known as lipodystrophy.

“It's been an up-and-down battle,” said Pusateri, of Oakland. “Really, with this HIV, you never know what's going to happen to you.”

Pusateri is among the oldest in a group of people observing a milestone many never imagined: 2015 is the first year the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has estimated more than half of people living with HIV may be older than 50.

“No one would have believed this 30 years ago,” said Ron Stall, director of the Center for LGBT Health Research at the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health.

Stall recently received a $2.1 million National Institutes of Health grant for a three-year study of what he calls “resiliencies” or the social and emotional characteristics of men who stayed healthy while living with HIV or who are at risk of contracting it.

Stall is beginning the study amid increased attention from doctors and medical researchers on how the human immunodeficiency virus and its treatments affect aging. Without treatment, life expectancy for someone with the virus is about 10 years, he said.

“When I first started doing this I never dreamed I'd be concerned about geriatric medicine, but here we are,” said Dr. Deborah McMahon, clinical director of UPMC's HIV/AIDS program. McMahon said she started working in HIV clinical care and research in 1988.

Treatments reduce patients' viral loads to extremely low levels in the blood, but don't cure HIV or AIDS. The virus remains in long-lived cells and continues to activate the body's immune system, McMahon said, causing inflammation that may accelerate chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease. HIV is linked with higher cancer risk. Essentially, McMahon said, HIV may accelerate aging.

Studying ‘strengths'

The first drug to treat the virus, known as AZT, inhibited the ability of HIV-infected cells to reproduce but caused anemia, nausea and vomiting. As treatments advanced, including the major development of protease inhibitors in the 1990s, newer drugs attacked HIV-infected cells at a later point in their life cycle. The two-pronged approach proved effective in lowering the virus to undetectable levels.

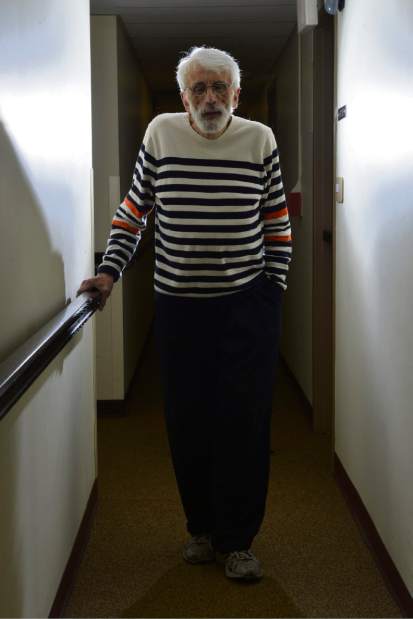

No treatments existed when the first available blood test showed Pusateri was HIV-positive in 1985. The virus worked unabated, devastating his immune system, and hospitalized him with a severe bout of pneumonia for the first time in 1991.

He took AZT and tried multiple drugs through the 1990s, including those known as d4T and ddI, which likely caused the neuropathy in his feet. In 1998, he started seeing McMahon, who prescribed a cocktail of drugs that dropped his viral load to an undetectable level.

As he approaches 79, the average life span of an American male, Pusateri is healthier than many younger men without HIV, McMahon said.

His success living with the virus makes him a likely candidate for Stall's resiliency study, which will survey men who participated in the Pitt Men's Study, a 30-year-old research project with residents of Pittsburgh, Baltimore, Chicago and Los Angeles. Stall's study will include 1,850 men from the study, including those who are HIV-positive and HIV-negative.

The study will examine specific qualities and conditions in the men's lives, Stall said. It will look at impacts of factors such as the resolution of internalized homophobia, the preservation of personal relationships, family building and connection with community, he said.

Stall said he will look for associations between those characteristics and how well people stick to a medical regimen their doctor recommends, which experts said is the most important element of living with HIV.

“Normally in the health sciences, we study deficits — we study weaknesses,” Stall said. “I'm trying to flip it, say, ‘Aren't strengths important, too?' ”

Support systems

Pusateri said he volunteers with patient-advocacy organizations, goes to church and receives help and support from two nieces. He credits his health in part to a positive outlook.

“I remember thinking to myself, ‘I'm not going to die,' and I just pushed that out of my mind,” he said. “I'm a very optimistic person.”

In nearly 30 years of seeing patients, McMahon said she has noted the value of resiliency and support from family and friends in getting patients to take care of themselves.

“Just in general, anyone who has a support system does a bit better,” she said. “And as you get older that becomes more important, because you start to rely on people.”

At the 30-year-old Pittsburgh AIDS Task Force, about half of 700 clients are older than 50, the organization said.

“It's a good thing that there are better medications, that people are living longer,” said Jason Herring, the organization's director of programs and communications. “That's one of the reasons we're here. ... But they are living with issues that normally you'd see in much older people.”

The organization is encouraging older people to get tested for HIV, saying doctors and patients can mistake HIV's symptoms for the normal effects of aging, missing the opportunity to start treatment early.

“Older folks may have more guilt built up and don't want to think about it,” Herring said. “They're in a mindset several years behind where we are now.”

Wes Venteicher is a Trib Total Media staff writer. Reach him at 412-380-5676 or wventeicher@tribweb.com.