Prints of Pulitzer-winning photo conjure memories of massacre

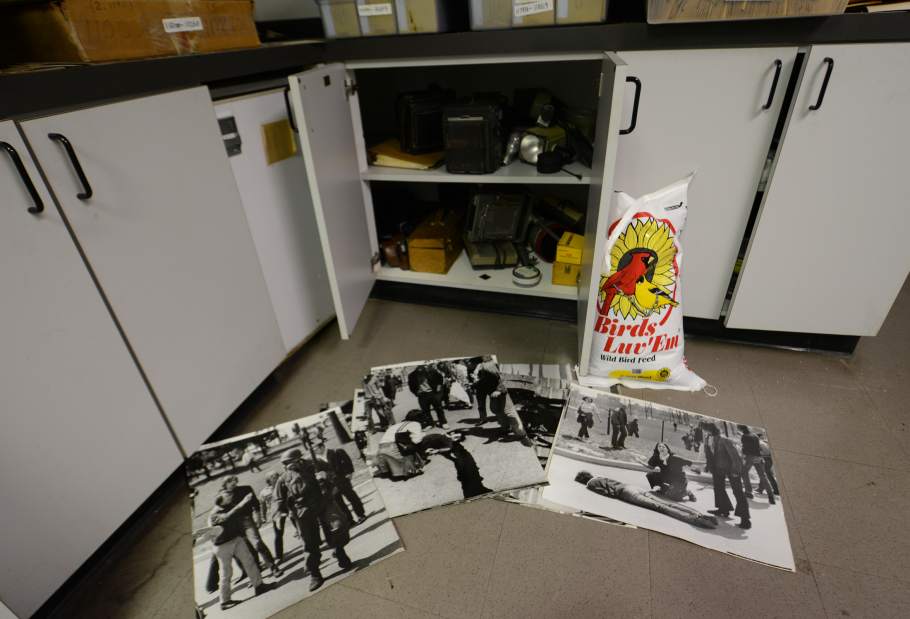

In the photo department at the Valley News Dispatch in Tarentum, there is a small room that has become a depository for all things antiquated and no longer useful.

A staffer recently unlocked the door and stepped in. He found boxes of negatives so old that their cardboard bottoms ripped open when lifted. In long-shut cabinets — some so ancient that the doors fell off their hinges — he found obsolete camera gear, stacks of newspapers and, mysteriously, bags of bird feed.

Then he opened a corner cabinet. There were cameras dating to the 1940s. And a dark space in the back.

He reached in and found a stack of old prints.

Though they were 46 years old, he recognized the photos at once.

“I'd heard stories about how the Valley newsroom handled the situation,” photographer Lou Ruediger said. “But finding them ... this is a real jewel.”

***

John Filo thought he had missed everything.

The Kent State University photojournalism student had been out of town that early May weekend in 1970 when protesters, incensed by the U.S. invasion of Cambodia, burned down the ROTC building and caused problems elsewhere. The National Guard was summoned.

“I was thoroughly depressed,” said Filo, who was 20 at the time. “I thought it was all over.”

That Monday morning, he talked to his professors.

“They said the story had changed: It's about student protests now,” he recalled. “They said, ‘You have an hour for lunch. Go out and see if you can get some student protest shots.' ”

So he went.

With no press credentials — his request had been denied even as his three roommates got gigs shooting for national publications — he found students congregating down a hill from some Guardsmen. The students were peaceful. Nobody expected problems.

Then a protester ran toward the Guardsmen. Well over 100 feet away, he waved a black flag in the air.

The Guardsmen raised their rifles, and Filo lifted his camera. And he got the shot.

“I said, ‘This is it!' ” Filo said. “I was really happy with it because it took a little foresight, a little movement, a little timing. It was the best picture I'd taken in my life.”

Then, with no warning, everything changed.

The Guardsmen opened fire.

Filo assumed they were firing blanks, so he never moved, even as others scattered. He noticed one Guardsman kneel and aim his rifle at him. Filo aimed his camera back and shot.

So did the Guardsman.

“There was a modern sculpture in front of me and to my right, and next to me was a tree,” Filo said. “The gun goes off, the sculpture just clangs and tree bark splinters off. I'm like, ‘Oh, man — some guy is using live ammunition.' I thought it was only one of them.”

It wasn't, and all around him, students took cover.

“People hiding behind trees, hiding behind 4-inch curbs ... any type of shelter,” he said. “How did I not get hit? I'm the only idiot who stood through the whole thing because I could see no reason for them to use live ammo. So I didn't believe they were.”

The shooting stopped.

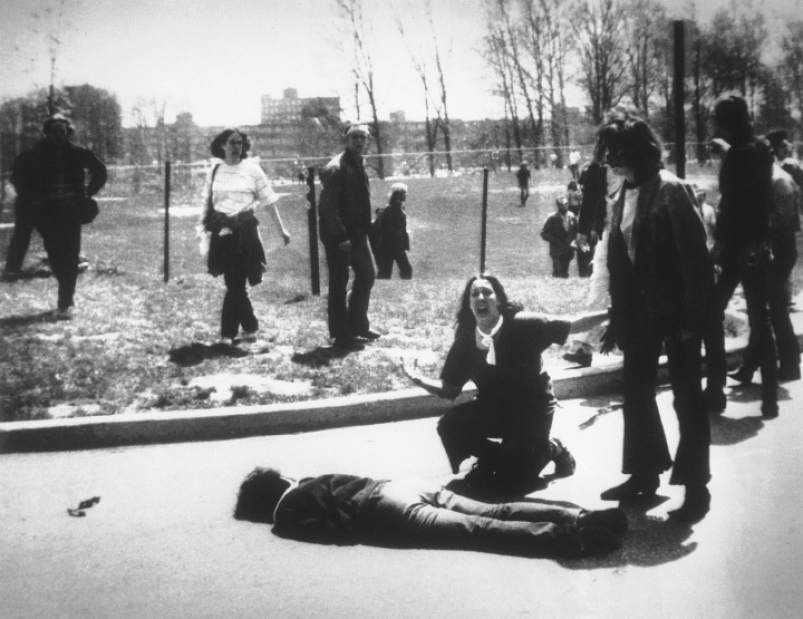

Filo saw a fellow student, Jeffrey Miller, directly in front of him, on the ground. A bullet had entered his mouth and exited the base of his skull. Blood streamed from his body.

Others were wounded, and students rushed to them. But they stayed away from the 20-year-old Miller. “Because he was dead,” Filo said. “When you looked at him, you knew: That's a dead person.”

Then she appeared.

Filo watched her run to Miller. He saw the realization and emotion build. And when she got to Miller, she dropped to her knees, raised her hands and screamed.

Filo pressed the button on his camera. Once again, he got the shot.

He did not know who she was. He did not know the image of her and Miller's body would become one of the most iconic photos in U.S. history.

All he knew was he needed to get this film developed. And that he had to get out of town.

“The initial radio reports said two students and two Guardsmen had been killed in a shootout,” Filo said. “Everyone thought, ‘Oh my God, it's another Nixon cover-up.' ... There were Guardsmen on every corner, the traffic lights in town were flashing, and more Guardsmen were arriving in military vehicles. I saw a Guardsman in a jeep literally cutting cables from telephone poles. They just dropped to the ground.

“I saw that, and I said, ‘I'm going to my apartment, grabbing some clothes, hiding this film and getting the hell out of this town.' ”

Filo worked for no one. But the Natrona Heights native had worked as a summer intern for the VND, then known as the Valley Daily News.

He raced out of town. He crossed the Pennsylvania state line, pulled into a rest stop and called chief photographer Chuck Carroll.

“Did you get anything?” Carroll asked.

“I think so,” Filo replied.

The entire photo staff awaited his arrival. The instant they saw the images, they knew they had something special. Editors wanted to hold it a day, to give the paper an exclusive.

Filo said no.

“It's now 5 or 6 p.m., and there's still this story of a shootout,” he said. “I said, ‘This wasn't a shootout. You have to start getting on the right story.' And that's what we did.”

They connected to the Associated Press photo line. An operator said Filo would have to wait to send images, that they already were receiving from the Akron Beacon Journal.

Filo told them: They weren't where I was.

“All right,” the operator relented. “Go ahead, TAR. What's your One?”

TAR stood for Tarentum. One meant the lead image.

Filo sent the photo of a girl screaming over Miller's body.

The line went silent.

Usually, there was chatter. Now, only white noise. Filo thought he had misdialed or hit a wrong switch.

Finally, the operator spoke: “Oh, man. Good picture. You have any more?”

The next day, Filo's lead shot was on the front page of major newspapers around the world. The photo, taken by an unemployed 20-year-old, won a Pulitzer Prize.

***

Forty-six years later, people still ask him about it.

Filo has not tired of answering.

“Because I definitely think I suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, and I think most people who were there that day did and continue to do so,” he said. “I had the nightmares. For many years, I was bothered by — How did I win a Pulitzer and Jeffrey Miller, who was 6 feet from me, ends up dead? How do you make sense of that? The answer is, you can't.”

He talks about it because to this day there is misinformation about what happened, he said. Some people tried to defend the Guardsmen, saying the dead students — Miller and three others — somehow had it coming: That they all had sexual diseases (they did not). That they were dope addicts (they were not).

“They had to vilify them to make it more palatable,” Filo said. “It still goes on, and it's just not true.”

Take the unnamed girl in the lead photo. Weeks later, it was discovered that her name was Mary Ann Vecchio, and that she was a 14-year-old runaway from Florida. “And there are still people who say, ‘She was a hippie runaway!' ” Filo said. “OK. Your point is?”

He talks about reactions. How at first, in the stunned silence, he took photos and nobody said a word. But then the mood turned, and people shouted at him for taking photos of a body.

One woman yelled at Filo to stop.

He yelled back: “Nobody is going to believe this happened!”

Filo understands her response. But he believes her second reaction is more important. Filo captured an image of it: She is kneeling by Jeffrey Miller's side, holding his hand.

“Because she didn't want him to die alone,” Filo said. “It's amazing how many people were affected by that day. She was as helpless as everyone else.”

Filo, 68, is vice president of CBS Photography Operations.

He has no idea why those prints were stashed in the dark corner of a room where he developed them or what they were used for. No one at the Valley does either. The editors working then are no longer alive.

This much is known: Staff stopped cleaning that room when Ruediger found the prints.

Because until the Valley can hire an archivist to properly preserve the other mysteries sure to be lurking there, that small room in the photo department will remain sealed.