Survivors of St. Patrick's Day Flood of 1936 remember rivers' rampage

They were evacuated in rowboats, some separated from their parents as they sheltered with distant family or strangers. They returned to find their belongings damaged or washed away — if their houses remained at all.

But today's survivors of the massive St. Patrick's Day Flood of 1936 don't remember the fear their parents likely felt as the Allegheny and Kiskiminetas rivers and adjacent creeks rose to historic levels. Rather, they remember a child's excitement.

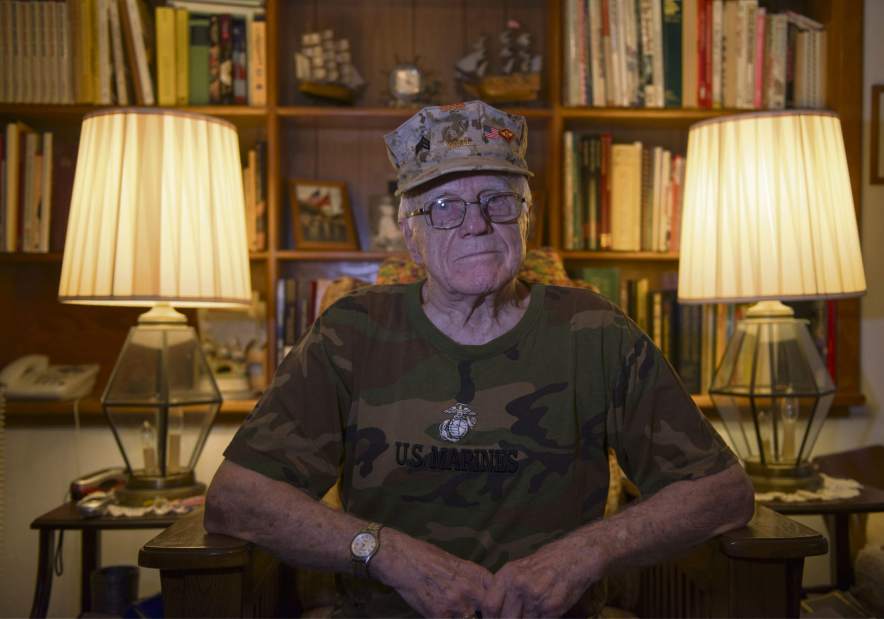

“I don't remember being scared,” said Anthony DiGirolamo. He was 13 when he climbed into a rescue boat from a second-story window in his family's Brackenridge home.

“It was an adventure for me,” said DiGirolamo, now 93 and living in Lower Burrell.

“We thought it was exciting,” said Maxine Bures Sweeney, 87, a Harrison resident who lived in Freeport 80 years ago. “I think I really didn't understand what all was happening.”

Sweeney's family left their Market Street home and briefly stayed with relatives in Leechburg. The water infiltrated their Freeport home's second floor — ruining bedding and any items they had not stored across the street in the second story of a lumber mill.

Gloria Christian Mangone, 87, said at first she was scared when her family left their East Sixth Avenue home in Tarentum amid concerns that an upriver dam would fail. But her fears turned to enthusiasm when her family was selected to spend the night in the home of Charles Howe, publisher of what was then the Valley Daily News.

“It was exciting, going up to Howe's house,” said Mangone, who now lives in New Kensington. “They were considered rich people. We stayed in their attic. Looking out the window down over the Valley was really exciting for us kids.”

Historic water rise

Mangone had a bird's-eye view of flooding not seen before or since in the Alle-Kiski Valley.

“Never, in all of modern history, was the river so high,” proclaimed New Kensington's Daily Dispatch and Tarentum's Valley Daily News in an article that appeared in both papers on March 19, 1936.

That's still true — the 46-foot crest reached on March 18, 1936, is the highest in recorded history on the Ohio River at The Point in Pittsburgh, according to National Weather Service records.

The 1935-36 winter season remains the ninth snowiest on record. Southwestern Pennsylvania experienced its third-rainiest March ever — including nearly 2 inches on March 17. The rain combined with melting snow to swell waterways over their banks.

The Kiski River at Vandergrift rose to a depth of nearly 42 feet — more than 15 feet above flood stage.

The Allegheny River depth also set records that still stand at the four local dams from Clinton in South Buffalo to Harmar, according to the weather service.

The dam between Natrona and Braeburn did not fail as Mangone's family feared, but the raging river eroded the Lower Burrell side and cut a new channel that threatened the Braeburn Steel Co. and the damaged railroad tracks and road.

The Army Corps of Engineers managed a crew of nearly 1,000 workers who used sandbags and rocks brought by train and barge to fill the 200-foot gap.

One of the steamboats assisting in the effort, the Elizabeth Smith, sank near the dam on March 25.

Other infrastructure was damaged or destroyed. Bridges along the Kiski River were wiped out, including the Apollo Bridge and a railroad bridge just upriver. The pedestrian bridge between Hyde Park and Leechburg was damaged, as was the footbridge to West Leechburg Steel Co., stranding workers at the plant.

Houses swept downriver

Property damage was immense. Houses swept from their foundations blocked the road to Leechburg in the North Vandergrift neighborhood of Parks Township.

The same was the case in Creighton in East Deer, where houses shifted onto then-Route 28 amid a double whammy of floodwaters from below and landslides off Boquet Hill from above.

More than 200 Kiski Valley homes were swept downriver. The Daily Dispatch wrote of people standing on the Vandergrift Bridge, rescuing residents from floating buildings.

After rowing away from their Ann Street home in Oakmont, the family of Joseph Hemmes never saw the house again. It washed down the Allegheny River and likely split apart against the Highland Park Bridge.

“The water came up, and everything went,” recalled Hemmes, now 90 and living in New Kensington. “You never seen it move like it did.”

Hemmes' daughter, Jerri Christie of Cheswick, said her family spoke of the disastrous day.

Hemmes' mother, Mary, baked bread that morning, and his father, Paul, went to work at the Scaife Co. metal manufacturing plant in Oakmont before returning home — with a boat — to rescue his family, which included six children.

Mary Hemmes had time to grab little aside from diapers for her baby. One document saved was Joseph Hemmes' birth certificate. The barely legible form includes a handwritten note from his mother that the “defacing is due to being in Flood of Mar. 18, 1936, at (foot) of Ann St.”

Herculean cleanup

In Brackenridge, the Stieren Avenue home of the Bavetz family flooded but stood firm.

“I bet there's still mud up in eaves of the basement,” said Frank Bavetz, now 89 and living in Harrison. “Things were built good back then.”

Not only did the house survive, so did his mother's prized new Maytag washing machine. It just needed a rebuilt motor after being flooded.

Also surviving were portraits from Austria of his father, uncle and grandparents. The framed photographs, now hanging in his Natrona Heights basement, still bear the water marks from the 1936 flood.

Cleanup was a herculean task, especially because many communities, ironically, had to conserve water as plants could not function. Electric and natural gas services were spotty as utilities dealt with damages.

“Mud, mud, mud!” is the memory of Mildred Paletta, who was a 6-year-old living in Brackenridge. “There was a lot of cleaning.”

And it wasn't just homes affected — businesses faced an unprecedented cleanup. Newspaper accounts referenced damage to major employers, including Alcoa in New Kensington, Allegheny Steel in Natrona, Braeburn Steel in Lower Burrell, Pittsburgh Plate Glass in Creighton, the United Engineering foundry in Vandergrift, West Apollo Steel Co. and the American Glue Co. in Springdale.

Scores of small businesses were inundated. Anthony DiGirolamo remembers cleaning his family's Brackenridge house on Third Avenue as well as the neighboring warehouse and Tarentum store for their retail and wholesale fruit businesses.

“We were shoveling mud for what seems like days,” he said. “We put lime around to kill bacteria.”

Health officials feared outbreaks of diseases such as typhoid. Vaccines were brought in, and residents were advised to sprinkle lime on flooded surfaces and to boil their drinking water.

DiGirolamo said his family had to discard all of their produce. The labels fell off the canned goods at neighboring Weissburg Meat Market; DiGirolamo said they put the cans in a “potluck” bin and sold them for 5 cents each.

“It took about 10 days before the business got going again,” DiGirolamo remembers. “We were in the house about two weeks after we started shoveling mud out. I never saw so much mud.”

Sunny outlook

Despite the devastation, St. Patrick's Day flood survivors can recall positive experiences.

Paletta remains being thankful for the help of the International Order of Odd Fellows and others who assisted them with clothing and other necessities.

“It was not a joyful thing, but everyone was very helpful,” she said.

Bavetz remembers being thankful for one aspect of flood destruction: “One good thing, it took out all the outhouses.”

Hemmes sums up the St. Patrick's Day Flood experience: “No matter how you look at it, it was quite a feat.”

Liz Hayes is a Tribune-Review staff writer. She can be reached at lhayes@tribweb.com or 724-226-4680.