https://archive.triblive.com/news/washington-county-judge-says-heroin-addicts-fare-better-in-treatment-than-prison/

Washington County judge says heroin addicts fare better in treatment than prison

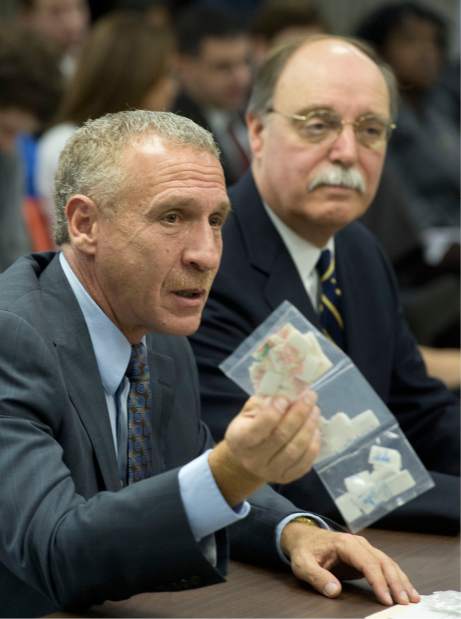

Barry Reeger | Tribune-Review

Detective Tony Marcocci, of the Westmoreland County Heroin Task Force, displays stamp bags of heroin while testifying to members of the State House Judiciary Subcommittee on Crime and Corrections with Westmoreland County District Attorney John Peck during a regional public hearing that focused on the law enforcement response to the state’s heroin epidemic at the Hempfield Township Municipal Building on Oct. 09, 2013.

(Part three of a six-part series on the effects of heroin on the Mid-Mon Valley.)

When John DiSalle served as a Washington County assistant district attorney from 1988 to 1996, prosecutors rarely saw heroin cases.

And those that came through the system generally involved middle-aged addicts.

“Now we have it across all walks of life, even middle school- and high school-aged children,” said DiSalle, now a Washington County Common Pleas Court judge. “It is more widely available, and it's inexpensive and easier to get than recreation drugs, even marijuana.”

DiSalle suggests the best way to battle the heroin epidemic lies with those abusing the drug.

“I think we must attack the market,” DiSalle said. “Of course, we have to prosecute the dealers, the ones bringing it and selling it. But as long as people are buying it, those drug dealers are going to find a way to bring it here.”

DiSalle said the judicial system is trying to focus heavily on treatment, education and rehabilitation.

He said it is possible to rehabilitate heroin addicts. But the more serious the addiction, the more difficult it becomes for rehabilitation, he added.

“I think people in recovery get a bad name,” DiSalle said. “There is so much in the news about those getting caught. We don't pay attention enough to those who are seeking help.”

DiSalle oversees the county drug court.

A person entering the 23-month program has to be screened and must have committed an offense serious enough to warrant a prison sentence of roughly two years.

The offender then is screened by the Washington Drug and Alcohol Commission Inc.

“The individual has to want to go into this program,'' DiSalle said. “I ask them, ‘Are you motivated and sincere about your recovery because we only have a limited number of spaces in program? And if you are only interested in attempting to avoid a jail term, I need to put someone in there that wants to recover.'”

The person starts with a drug and alcohol treatment program. From there, he or she receives education and performs community service.

“Accountability is key – they are tested often – and there are sanctions for violations of the program,” DiSalle said.

“They get incentives and rewards for doing well. It can be anything from recognition to actual nominal gifts like gifts cards to graduating out of the program early.”

The program has been successful and has saved money over the cost of traditional incarceration, DiSalle said.

Westmoreland County District Attorney John Peck understands the impact of heroin.

“It takes up so much of my day. It's everywhere,” Peck said.

“In terms of deaths as a result of heroin and the enormous amount of crime in an effort to obtain heroin, the enormous amount of crime in an effort to sell it and the enormous amount of crime in an effort to obtain money to buy it, yes it is an epidemic.”

Peck said his office is committed to obtaining treatment for addicts who run afoul of the law as an alternative to traditional prosecution.

Peck's office has placed collection boxes at police departments across the county to provide places for people to drop off unused prescription drugs.

“Half of the overdose deaths are due to prescription drugs, and a lot of people who abuse heroin are saying it began with prescription drugs,” Peck said.

“Treatment has to be a large part of it simply because it is the only way the epidemic can be stemmed.”

The veteran district attorney said efforts will continue to prosecute those who sell heroin.

“The supply always seems to be available,” Peck said.

Peck said state, county and local police are committed to arresting those who provide heroin that results in overdose deaths.

Peck said the heroin epidemic is the latest battle in the 50-year war on drugs.

“It consumes us, but it is a war that must be fought on every front,” Peck said.

When Washington County District Attorney Gene Vittone worked as a paramedic in Washington in the 1990s, he never responded to a single overdose call.

In 2014, 43 overdose cases were reported in the county. Over the past four years, 208 overdoses were reported in the county.

Vittone said heroin is “a multifaceted problem.”

One aspect requires greater enforcement efforts.

“We're going after the dealers,” Vittone said of his drug task force. “We're going after the people putting the poison on the streets.”

Another aspect is education, Vittone said. His office conducts seminars and educational programs in schools.

Vittone said one goal is to get help for addicts in an effort to reverse destructive and criminal behavior that comes with drug addiction. Another is to change public perception, noting that many who progress to heroin begin with pain pills – often after suffering workplace injuries.

His office launched a diversion program for nonviolent offenders that replaces incarceration with quick access to drug treatment.

The office uses drug forfeiture proceeds to supply police with naloxone, marketed under the trade name Narcan. The drug counters the effects of such opioids as heroin in overdose cases.

Vittone is working with Pittsburgh-based U.S. Attorney David Hickton on efforts to interrupt the supply of heroin into Washington County.

“Hopefully we're getting the word out that Washington County is not a good place to sell this stuff,” Vittone said.

Chris Buckley is a staff writer for Trib Total Media. He can be reached at cbuckley@tribweb.com or 724-684-2642.

Copyright ©2026— Trib Total Media, LLC (TribLIVE.com)