William Penn Hotel remains regal through its 100 years

Every large city has a “Grande Dame” among its hotels — a prominently situated, architecturally significant, older hotel so entwined with the history of the city that it lends its prestige to the city as a whole.

These are hotels like the Plaza in New York, the Drake in Chicago, the Copley in Boston, the St. Francis in San Francisco and, indisputably, the William Penn here.

That's the way an old, employee-written history of the William Penn tells it, and it's an especially pertinent insight today. The hotel, known now as the Omni William Penn, will be exactly 100 years old this March — having reigned as the town's leading hotel for a large part of our city's history.

Whenever U.S. presidents have come to town, it seems like they've stayed at or given speeches at the William Penn. When the original Nixon Theater was just across Sixth Avenue, the hotel became known for all the show business stars and entertainers who stayed there. Some parts of the hotel once functioned as exclusive gentlemen's clubs in the 1920s and '30s, and there were several formal dining rooms and supper clubs, as well. Lawrence Welk first performed his “Champagne Music” at the William Penn in the late '30s, and the original bubble-making machine that Welk later used is on display in a hall behind the lobby.

And during Prohibition? Well, the hotel even sheltered what's said to have been a small “speakeasy,” hidden beneath its main stairways. It has recently been re-created there with a lounge that specializes in cocktails popular at the time.

The hotel has had eight changes in ownership in the 100 years since it was built by Henry Clay Frick to fulfill his desire to have a world-class hotel in the city. And it has undergone numerous renovations, updates and revivals since. Yet, amazingly, like its reputation, the architectural attributes of this grand hotel survive intact.

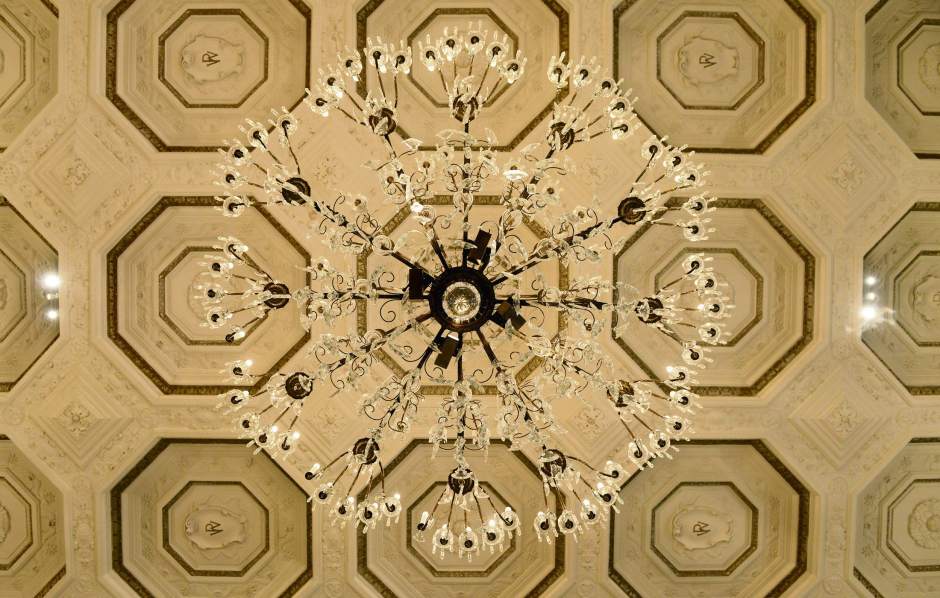

The balconied Grand Ballroom, a magnet for “high society” events over the years, looks almost exactly the way it looked when the hotel opened in 1916. The famous Art Deco-style Urban Room, adjacent to the ballroom, is close to totally intact from when it was added to the hotel in 1929. The sedate Terrace Room, a formal dining room at one side of the main lobby, is still a lot like the 1916 original.

And though the main lobby has often been altered in one way or another with successive ownership changes, losing along the way its original walnut paneling, that hasn't diminished its overall architectural dignity either.

It is still a warm and welcoming place, and the main lobby is filled with folks coming and going almost any time of any day. To add to all the activity, “High Tea” is served in the afternoon on the interior terrace. It attracts young people, as well as the occasional real Grande Dame.

The hotel was designed in a Renaissance Revival style — which means it features tall interior arches and round-topped windows in the main public rooms and lots of carved or molded Classical details everywhere, including sumptuously decorated ceilings and cornices, even in some hallways. (Wherever you go in this hotel, be sure to look up.)

Even a new fitness center for guests — a necessary amenity in any hotel today — is housed respectfully in a former club room where dark wood paneling and a marble fireplace date to the hotel's founding.

The original 1916 hotel and a 1929 addition were both designed by Benno Janssen, a local architect trained at the Ecole de Beaux Arts in Paris. He was one of the best and most prolific local architects this city has known. He was a favorite of the local establishment, practicing in Pittsburgh from 1905 until he retired in 1938. His patrons, besides Frick, included Andrew and Richard Beatty Mellon and Edgar Kaufmann.

Janssen designed the Rolling Rock Stables, Long Vue Country Club, the Mellon Institute, the Pittsburgh Athletic Association and an addition to the Duquesne Club, as well as other public buildings and many private residences. His numerous works for the Kaufmann family included the main building of the former Kaufmann's Department Store complex at Fifth and Smithfield, Downtown, as well as Edgar Kaufmann's Norman-style house, known as La Tourelle, in Fox Chapel.

In a beautifully illustrated survey of Janssen's career called “The Architecture of Benno Janssen,” author Donald Miller describes the man this way: “He was particularly attentive to romantic details that gave character to his buildings. Ambitious, courtly, almost reserved but approachable, he had qualities that would quickly advance him as an architect and businessman.” Janssen, Miller notes, joined all the best clubs in the city, and his manner and his friendships clearly advanced his career.

At one time, the hotel had 1,600 guest rooms and boasted of being the largest hotel between New York and Chicago. Those earlier rooms were far smaller, though, than what hotel guests expect today (even the beds were small). The rooms have since been substantially enlarged so that there are 597 today, including 38 suites.

The Urban Room

In addition to Benno Janssen's architecture, one specific part of the William Penn has landmark status of its own, and that is the Urban Room on the 17th floor, a 1929 ballroom adjacent to the main ballroom. It is named for its designer, Joseph Urban, an immigrant Viennese architect and New York stage designer who is famous for his modernistic work during the art deco era of the '20s and '30s.

He also did the interiors of supper clubs and ballrooms in his distinctive art deco style for a number of hotels across the country. But little of that hotel work survives — except for the room here.

The Urban Room feels both somber and elegant today. It has tall panels of reflective black Carrara Glass trimmed with gilt borders. In between are 14 elaborate murals that are essentially, as befits art deco style, geometrical and floral at the same time.

The room presents a bit of a conundrum for the hotel's owners today, though. The murals — once exceedingly colorful — have been considerably darkened over the years by smoke. Some, perhaps, was the smoke that was part of Pittsburgh's history, some the accumulation of cigarette smoke from thousands of banqueteers who have used the room over its 87 years.

To clean the murals carefully might take six months. But the room is also one of the hotel's main revenue generators, and closing it for six months isn't very desirable either. A solution hasn't yet been found.

John Conti is a former news reporter who has written extensively over the years about architecture, planning and historic-preservation issues.s