Islamists call for 'Day of Rejection' in Egypt

CAIRO — Huge crowds remained in Tahrir Square on Thursday, celebrating the military's ouster of Mohamed Morsy as Adly Mahmud Mansour, chief of Egypt's constitutional court, was installed as interim president.

The jubilation extended to Egypt's moribund stock market, which rebounded 7.3 percent.

Mansour, little known to many Egyptians, pledged to hold elections based on “the genuine people's will.”

But the spokesman for Morsy's Muslim Brotherhood, whose leaders continue to be rounded up, said the group would not cooperate with the new regime. Gehad el-Haddad called on Egyptians to make Friday a “Day of Rejection.”

That protest, to begin after weekly prayers, poses an early test of Morsy's support and how the military will deal with it.

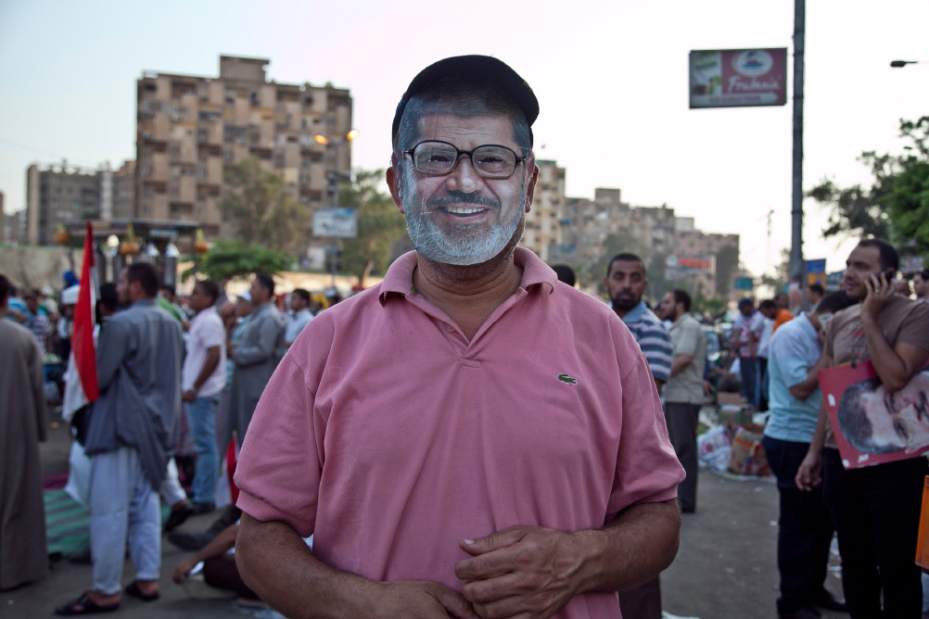

Islamists rallied in a suburb of the capital, many in the mostly male crowd carrying clubs or metal poles.

Their anger showed how divided the most populous Arab nation remains — and how great the risk of violence may be.

“With our souls and blood, we will sacrifice for you, O Morsy!” shouted one man.

Muataz Moussa, 35, who insisted he is not a member of the Brotherhood, said “desperate” Egyptians would turn to al-Qaida because of the Brotherhood's failed foray into democratic politics.

The Brotherhood won control of Egypt's parliament in 2011 elections; Morsy won election last June. All that ended when the military arrested Morsy; several aides; the Brotherhood's supreme leader, Mohamed Badie; and other officials, and placed the government in civilian hands until elections are held.

Security sources said Badie, the spiritual leader of the Brotherhood for the past three years, was arrested in the northern city of Marsa Matrouh, near the Libyan border.

The army said it acted to end economic collapse and growing unrest; many Egyptians have feared that Morsy and the Brotherhood were turning Egypt into an Islamist state.

“I am a law-abiding citizen, and the army is surrounding us from everywhere,” Moussa said. Gesturing to the men around him, he added: “Now all these people here … they are a time bomb.”

He said Egypt has been divided “into master and slaves, just like it was under (Hosni) Mubarak,” the dictator deposed in 2011's revolution. “We are the slaves,” he said bitterly.

Several of the men dismissed as “thugs” the wide spectrum of Egyptians who turned out in the millions nationwide to demand Morsy's resignation; they blamed the media for the protests.

“We want you to send a message to the West,” said teacher Sobhi Ali Youssef. “What about freedom and democracy now?”

He said Islamists “went to the ballot box, but the enemies of democracy refused this. We will all stay here, united, until Dr. Morsy is made president again.”

Others in the crowd promised to demonstrate nationwide and to engage in civil disobedience.

Muhamed Ismail, 36, said he returned to Egypt from Chattanooga, where he owns a jewelry shop, to support democracy.

“What we see now is a complete assassination of democracy,” he said. “When you have an Islamist or a group of people and you put them in the corner, what do you expect to happen? If you put a cat in a corner … she is going to attack.

“I expect violence and bloodshed everywhere, 100 percent.”

Armored vehicles blocked roads near Cairo University as soldiers scuffled with about a dozen chanting protesters who held pro-Morsy signs.

The United Nations, the United States and some other world powers avoided condemning Morsy's removal as a military coup. To do so might trigger sanctions.

Army intervention was backed by millions of Egyptians, including liberal leaders and religious figures who expect new elections under a revised set of rules.

Egypt's armed forces have been at the heart of power since officers staged the 1952 overthrow of King Farouk.

The protests that spurred the military to step in this time were rooted in a liberal opposition that lost elections to Islamists. Their ranks were swelled by anger over broken promises on the economy and shrinking real incomes.

The downfall of Egypt's first elected leader, who emerged from the “Arab Spring” revolutions that swept the region in 2011, raised questions about the future of political Islam, which only lately seemed triumphant.

Betsy Hiel is the Tribune-Review's foreign correspondent. Email her at bhiel@tribweb.com. Reuters contributed to this report