In defense of 'price gouging'

When a Muslim extremist took hostages in an Australian café this month, effectively shutting down Sydney's central business district, the ride-sharing company Uber sprang into action by raising its prices? Public disgust, both in Sydney and around the world, was palpable, and Uber backpedaled in the face of “price-gouging” criticism. But it shouldn't have.

Uber has repeatedly taken heat for “surge pricing” — its practice of raising its prices when there is greater demand for its service. But this is what always happens in a free market. Always and everywhere — not only in emergencies — we face the problem of deciding who gets access to limited resources.

No rationing system is perfect but a free-market price is the best solution humans have developed, because a market price does two important things: It encourages consumers to consume scarce resources judiciously by making purchasing more costly and it encourages entrepreneurs to get more resources into consumers' hands by making selling more lucrative.

In Sydney, there were people in the central business district who wanted to leave but had no rides out. Uber saw this and raised its rates significantly. This did two things: Some people who had a lesser need to get out decided to stay rather than to pay the surge prices, thereby freeing up cars for people who had greater needs, and some drivers who weren't working decided to get their cars on the streets as quickly as possible, thereby increasing the total number of cars available.

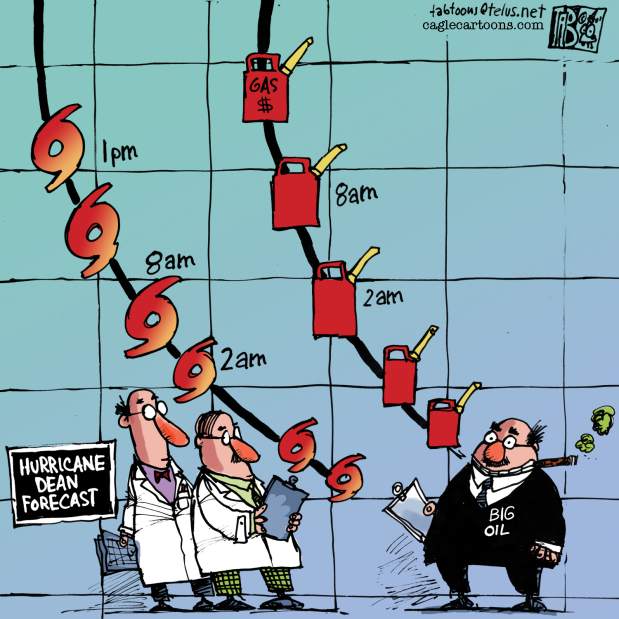

Railing against price increases, or even legislating against “price gouging” as we do in the United States, doesn't solve the underlying problem of scarcity. It only masks the symptom. A price spike is a messenger that announces a problem and a herald that summons the problem's solution. “Price gouging” is the mechanism that gets entrepreneurs to provide more of the resource quickly and, at the same time, encourages people to consume less of it.

When the black-market price of gas in New Jersey spiked to $5 per gallon after Hurricane Sandy, everyone had an incentive to cut back on their consumption of gas. This left scarce gas available for those who were willing to pay the higher price. Who was willing? People are quick to respond “the rich.” But far outnumbering the rich are the grocers who needed to fuel generators to keep millions of dollars worth of food from spoiling; ambulance companies and fire departments that needed to move emergency vehicles; and hospitals that needed to keep lifesaving machines running.

In short, the people who were willing (albeit not happy) to pay $5 per gallon were the very people whom we would want to have the gas in the first place. By making it extra costly to buy gas, the high price ensured that the scarce gas would be available for those who had the greatest need.

When we regulate the market during times of scarcity, we prevent markets from doing what they do best: balancing our wants with our abilities. Whether a ride out of a dangerous area, gasoline in the wake of a natural disaster or anything else, anti-price gouging efforts short-circuit important market incentives.

Would it be nice if people in Sydney volunteered to drive those in need? Would it be nice if people in hurricane-ravaged areas voluntarily purchased less gas so that those in need could purchase more? Absolutely. And markets don't prevent people from doing those things. They simply pick up the slack when volunteer efforts are inadequate. And in times of greatest need, volunteer efforts are almost always inadequate.

Antony Davies is associate professor of economics at Duquesne University. James R. Harrigan is director of academic programs at Strata in Logan, Utah.