Penn State is college football's latest culture shock

Kenny Jackson would like the world to know that the Penn State football culture never changed since he was catching passes for the Nittany Lions during the early 1980s.

" We changed,” said Jackson, an All-America receiver who later became an assistant coach at Penn State and with the Steelers. “Everyone is looking at football as a culture instead of looking at us as a culture. The game is so money-driven. When I came to Penn State, we played three times a year on TV, and that was unbelievable. You had to play Notre Dame or Michigan to get on TV.”

Nearly every Penn State game is on TV now and will continue to be despite strict sanctions announced by NCAA president Mark Emmert on Monday. During his nationally televised statement from Indianapolis, Emmert used the word “culture” seven times. The Freeh Report, on which the sanctions were based, cited a “culture of reverence” for football that fostered an alleged cover-up by coach Joe Paterno and other administrators of Jerry Sandusky's sexual abuse of children.

But what the Penn State football culture actually means and represents and whether it grew “too big to fail,” in Emmert's words, and spawned a wrenching scandal that extends beyond the college football landscape is viewed in different ways. To some, it was embodied by Paterno's “Grand Experiment,” which melded quality athletics with sound academics.

“The Grand Experiment worked, and anyone who says it didn't doesn't know what they're talking about,” said Lou Prato, a former broadcast journalist who is Penn State's unofficial football historian.

“I never sensed (the culture) was too big,” said librarian emeritus Lee Stout, who was the university archivist for 27 years. “If ‘too big' results in booster scandals, if ‘too big' results in pressure bringing in students who really aren't qualified to be college students, if ‘too big' results in tampering with the faculty grading of athletes, no, I never sensed that.”

College football is a different game off the field than it was when Jackson played 30 years ago. Penn State this season will be allowed to keep the nearly $21 million in TV revenues it will make from playing in the Big Ten. Before starting Big Ten play in 1993, the university made about $6 million from TV.

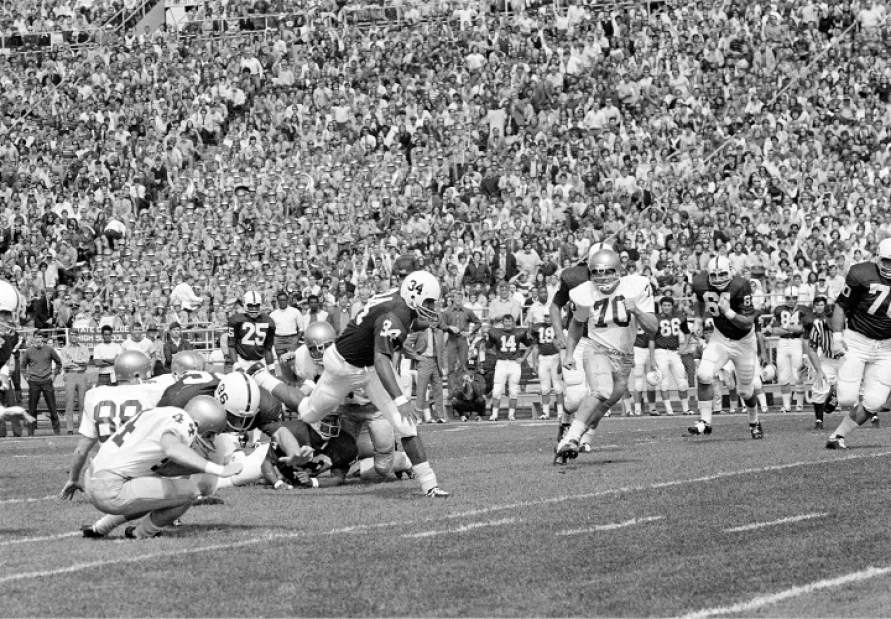

In 1966, Paterno coached his first home game in front of nearly 41,000 fans at Beaver Stadium. The crowd at his last home game in 2011 numbered more than 97,000, which was about 9,000 short of filling the nation's second-largest stadium.

What changed? Everything. In a 1986 Sports Illustrated story on Paterno being named the magazine's “Sportsman of the Year,” he recalls showing one of his early recruits, Jack Ham, the Nittany Lions' new weight room.

“It's not like the old days,” Paterno told Ham. “It's a year-round thing now. The competition is at such a level that you've got to lift weights and run a conditioning program year-round. I just don't know if its worth it.”

The expanding football culture at Penn State did not occur in a vacuum; it mirrored the growth of the school in enrollment, endowments and academic resources. It also reflected college football mushrooming into a multi-billion dollar enterprise vital to the identities of the NCAA member institutions, a big business in which head coaches are paid like corporate CEOs while their schools are firing professors.

In 1999, for example, the Louisiana State president said, “The critical role of our football program is clear — it is of vital importance to the entire LSU community: our students, our fans and alumni worldwide and the state of Louisiana. Simply put, success in LSU football is essential for the success of Louisiana State University.”

Those were the words of Mark Emmert.

“I would agree that the football culture was very strong at Penn State, but I would quickly add that in no way does that make Penn State unique,” university historian Michael Bezilla said. “It is strong at many, many universities.”

Asked if he were comfortable with the football culture at Penn State, Bezilla said, “In some respects, yes, and in some respects, no.” He would not elaborate.

“The culture was inbred, and it's not unique to Penn State,” said consultant Todd Turner, who was athletic director at Connecticut, Vanderbilt and Washington. “They just happen to be dealing with a really volatile issue. The same type of culture exists in other programs. How they handle their liabilities helps determine how they're perceived.”

Asked about the Penn State “culture” on ESPN, longtime college football broadcaster Brent Musburger said, “It revolves around big-time athletes and it is never, ever gonna be without abuses because winning is everything to all of these schools. ... The only way to change the culture would be to yank the program away from academics and pay these youngsters. But that's not gonna happen.”

Speaking of perpetual conference realignments and the vast riches to be gained from the new college playoff system, Turner said, “I think we're going through a cultural change in college athletics that's really scary.”

Turner said programs headed by ultra-successful, highly-paid “legacy” coaches are especially vulnerable because of the cultures those same coaches created.

“They rightfully feel that their way works for them, but there's danger in that,” he said. “And the danger is you become so indoctrinated in the culture that you don't question it.”

Bob Cohn is a staff writer for Trib Total Media. He can be reached at bcohn@triblive.com or 412-320-7810.